Downburst

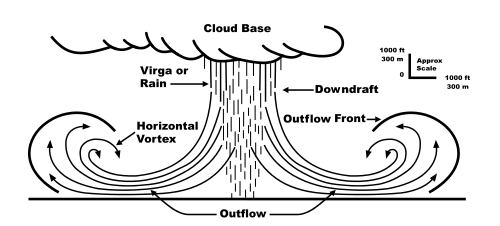

In meteorology, a downburst is a strong downward and outward gushing wind system that emanates from a point source above and blows radially, that is, in straight lines in all directions from the area of impact at surface level.

Downbursts are most often created by an area of significantly precipitation-cooled air that, after reaching the surface (subsiding), spreads out in all directions producing strong winds.

A rare variety of dry downburst, the heat burst, is created by vertical currents on the backside of old outflow boundaries and squall lines where rainfall is lacking.

This detection equipment helps air traffic controllers and pilots make decisions on the safety and feasibility of operating on or in the vicinity of the airport during storms.

Wakimoto (1985) developed a conceptual model (over the High Plains of the United States) of a dry microburst environment that comprised three important variables: mid-level moisture, cloud base in the mid troposphere, and low surface relative humidity.

[9] These downbursts rely more on the drag of precipitation for downward acceleration of parcels as well as the negative buoyancy which tend to drive "dry" microbursts.

Melting of ice, particularly hail, appears to play an important role in downburst formation (Wakimoto and Bringi, 1988), especially in the lowest 1 km (0.6 mi) above surface level (Proctor, 1989).

[12] In the United States, such straight-line wind events are most common during the spring when instability is highest and weather fronts routinely cross the country.

[citation needed] The formation of a downburst starts with hail or large raindrops falling through drier air.

Hailstones melt and raindrops evaporate, pulling latent heat from surrounding air and cooling it considerably.

Due to interaction with the surface, the downburst quickly loses strength as it fans out and forms the distinctive "curl shape" that is commonly seen at the periphery of the microburst (see image).

Finally, the effects of precipitation loading on the vertical motion are parametrized by including a term that decreases buoyancy as the liquid water mixing ratio (

) increases, leading to the final form of the parcel's momentum equation: The first term is the effect of perturbation pressure gradients on vertical motion.

In some storms this term has a large effect on updrafts (Rotunno and Klemp, 1982) but there is not much reason to believe it has much of an impact on downdrafts (at least to a first approximation) and therefore will be ignored.

Precipitation particles that are small, but are in great quantity, promote a maximum contribution to cooling and, hence, to creation of negative buoyancy.

[17] Heat bursts are chiefly a nocturnal occurrence, can produce winds over 160 km/h (100 mph), are characterized by exceptionally dry air, can suddenly raise the surface temperature to 38 °C (100 °F) or more, and sometimes persist for several hours.

[18] Downbursts, particularly microbursts, are exceedingly dangerous to aircraft which are taking off or landing due to the strong vertical wind shear caused by these events.

[19] The following are some fatal crashes and/or aircraft incidents that have been attributed to microbursts in the vicinity of airports: A microburst often causes aircraft to crash when they are attempting to land or shortly after takeoff (American Airlines Flight 63 and Delta Air Lines Flight 318 are notable exceptions).

The plane would then travel through the microburst, and fly into the tailwind, causing a sudden decrease in the amount of air flowing across the wings.

The strongest microburst recorded thus far occurred at Andrews Field, Maryland, on 1 August 1983, with wind speeds reaching 240.5 km/h (149.4 mph).