Gray mouse lemur

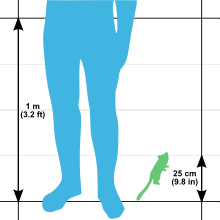

Weighing 58 to 67 grams (2.0 to 2.4 oz), it is the largest of the mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus), a group that includes the smallest primates in the world.

Although threatened by deforestation, habitat degradation, and live capture for the pet trade, it is considered one of Madagascar's most abundant small native mammals.

[13] M. murinus remained the only species of its genus, as well as the name used for all mouse lemurs on Madagascar, between the first major taxonomic revision in 1931 and an extensive field study conducted in 1972.

The field study distinguished the brown mouse lemur, M. rufus—then considered a subspecies—as a distinct, sympatric species in the southeastern part of the island.

[15][16][17][18] The gray mouse lemur shares many traits with other mouse lemurs, including soft fur, a long tail, long hind limbs, a dorsal stripe down the back (not always distinct), a short snout, rounded skull, prominent eyes,[10] and large, membranous, protruding ears.

[24] The gray mouse lemur tends to prefer lower levels of the forest and the understory, where branches and vegetation are dense.

[6][9] There is also an isolated and disjointed population in the southeastern part of the island, near Tôlanaro and the Andohahela National Park, up to the Mandena Conservation Zone.

[24] Nectar is also a part of the gray mouse lemur's diet, making it a potential pollinator for local plant species.

[24] The gray mouse lemur is nocturnal, sleeping during the day in tree holes lined with leaf litter or purpose-built spherical nests constructed from dead leaves, moss and twigs.

[19] In the dry season, the gray mouse lemur faces the challenge of exploiting sparsely distributed feeding resources efficiently.

It is believed that rather than using a route-based network, the gray mouse lemur has some sense of mental representation of their spatial environment, which they use to find and exploit food resources.

[24] Studies with captive gray mouse lemurs have shown that vision is primarily used for prey detection, although the other senses certainly play a role in foraging.

At both Marosalaza and Mandena, beetles are the primary insect prey, although moths, praying mantids, fulgorid bugs, crickets, cockroaches, and spiders are also eaten.

[6][7][9] Its diet is seasonally varied and diverse in content, giving it a very broad feeding niche compared to other species such as the Madame Berthe's mouse lemur.

[8][14][33] This rare trait in primates,[34] coupled with the ease of observing the species within its wide geographic distribution[6] and its good representation in captivity,[35] makes it a popular subject for research as a model organism.

[6][14] At Kirindy Forest, both sexes share the same daily torpor, yet during the dry season (April/May through September/October), females become completely inactive for several weeks or up to five months to conserve energy and reduce predation.

However, males rarely remain inactive for more than a few days and become extremely active before the females revive from torpor, allowing them to establish hierarchies and territories for the breeding season.

By entering extended torpor, sometimes referred to as hibernation, this would reduce the thermoregulatory stress in females,[33] whereas males remain more active in preparation for the upcoming mating season.

During the cooler months of May though August, the species selects tree holes closer to ground level, where ambient temperatures remain more stable.

This is because variations in gray mouse lemur abundance are linked to their capacity to enter torpor during the dry season, especially for females, which tend to hibernate longer than males.

[39][40] Before the discovery that ocean currents were the opposite of what they are today, thus favoring such an event,[41] it was thought that it would have taken too long for any animal not capable of entering a state of dormancy to survive the trip.

[7] Genetic studies indicate that females arrange themselves spatially in clusters ("population nuclei") of related individuals, while males tend to emigrate from their natal group.

In the more open dry forest habitats favored by the gray mouse lemur, trill calls are more common and effective since they carry faster and are less likely to be masked by the wind, while chirp calls are more common in the brown mouse lemur, which favors closed rain forest habitats.

Research has shown that the male mouse lemurs consciously manipulate the dialect to resemble those of their neighbors, when transferred from their home to a new neighborhood.

[24] During the breeding season, male testes increase significantly in size,[6] facilitating sperm competition due to female promiscuity.

Studies with the gray mouse lemur have shown that the optimal insemination period, during which a male is most likely to sire offspring, occurs early during a female's receptivity.

In the event of offspring adoption, when a parent dies and a closely related female takes over care, it is believed that this is beneficial to groups with high mortality risk.

[1] Its greatest threats are habitat loss from slash-and-burn agriculture and cattle-grazing, as well as live capture for the local pet trade in the northern and southern parts of its range.

[1][6] One study found nine species of parasites in the fecal matter of the gray mouse lemur living in forests that suffered degradation and fragmentation.

In 1989, more than 370 individuals were housed by 14 International Species Information System (ISIS) and non-ISIS institutions across the United States and Europe, 97% of which were captive born.