Microchess

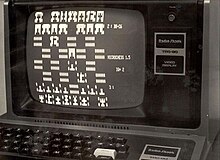

The game was ported to many other microcomputers such as the TRS-80, Apple II, Commodore PET, and Atari 8-bit computers by Micro-Ware and its successor company Personal Software (later VisiCorp) between 1976 and 1980, with later versions featuring graphics and more levels of play.

He developed it with the aim of making a product that could be widely sold, rather than as the most advanced chess engine possible.

The program can run at one of three speeds: Respond instantly, after calculating for 5–10 seconds, or use enough time that a full game may last an hour.

Jennings had wanted to create a chess program for many years after reading a Scientific American article on the subject.

Upon reading an article about MOS Technology's new KIM-1 microcomputer, Jennings decided to buy one and try writing his own program.

Over the next six months, he continued to iterate on the game, improving the computer's ability to understand moves and strategy while working within the KIM-1's limitations, including its 1kB of memory.

Despite the newsletter not mentioning Jennings's contact information, he received calls and letters from enthusiasts asking when the game would be complete.

Additionally, there was no commercial software market and most programs were distributed via printed source code in books and magazines to computer enthusiasts, the target audience of the game.

[10] Chuck Peddle, president of MOS Technology, offered to buy the rights to the game for $1,000, but Jennings refused to sell, believing his mail-order sales would make more.

[13] Versions of Microchess were released for other microcomputer in 1977, with minimal changes as Jennings was not interested in improving the program, only selling it more widely.

[14] A version for the Altair 8800 was produced in April 1977, with the port done by Terry O'Brian, a member of the local Toronto computer club.

[7][22][23][24] Over 1,000 copies of the game were sold by mid-1977, leading Jennings to quit his job and run Micro-Ware full-time after coming home one day and finding two bags of mail filled with orders for Microchess.

[17] Jennings did not disagree with criticism of the game's skill: "I still think that part of the commercial success of Microchess was that it was beatable and made stupid mistakes, just like an amateur human player.

[31] Jennings later noted that Micro-Ware sold many more early copies of the game for the KIM-1 than for the Altair 8800 microcomputers, despite the latter being much more popular.

[32] Jennings stopped playing chess for many years: "Programming Microchess actually ruined my game because I was paying so much attention to what the computer was doing, and since it was for testing, I was avoiding taking advantage of the weak parts of the algorithm.