Gravitational microlensing

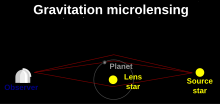

When a distant star or quasar gets sufficiently aligned with a massive compact foreground object, the bending of light due to its gravitational field, as discussed by Albert Einstein in 1915, leads to two distorted images (generally unresolved), resulting in an observable magnification.

Ideally aligned microlensing produces a clear buffer between the radiation from the lens and source objects.

Such lensing works at all wavelengths, magnifying and producing a wide range of possible warping for distant source objects that emit any kind of electromagnetic radiation.

Microlensing has also been proposed as a means to find dark objects like brown dwarfs and black holes, study starspots, measure stellar rotation, and probe quasars[1][2] including their accretion disks.

Thus, unlike with strong and weak gravitational lenses, microlensing is a transient astronomical event from a human timescale perspective,[10] thus a subject of time-domain astronomy.

[12] The first successful resolution of microlensing images was achieved with the GRAVITY instrument on the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI).

Events, therefore, are generally found with surveys, which photometrically monitor tens of millions of potential source stars, every few days for several years.

This is because these deviations – particularly ones due to exoplanets – require hourly monitoring to be identified, which the survey programs are unable to provide while still searching for new events.

The question of how to prioritize events in progress for detailed followup with limited observing resources is very important for microlensing researchers today.

In 1801, Johann Georg von Soldner calculated the amount of deflection of a light ray from a star under Newtonian gravity.

Einstein's prediction was validated by a 1919 expedition led by Arthur Eddington, which was a great early success for General Relativity.

Gravitational lensing's modern theoretical framework was established with works by Yu Klimov (1963), Sidney Liebes (1964), and Sjur Refsdal (1964).

In 1992, Paczyński founded the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment, which began searching for events in the direction of the Galactic bulge.

During this time, Sun Hong Rhie worked on the theory of exoplanet microlensing for events from the survey.

[32] EROS subsequently published even stronger upper limits on MACHOs,[31] and it is currently uncertain as to whether there is any halo microlensing excess that could be due to dark matter at all.

The SuperMACHO project currently underway seeks to locate the lenses responsible for MACHO's results.

[citation needed] Despite not solving the dark matter problem, microlensing has been shown to be a useful tool for many applications.

In addition to these surveys, follow-up projects are underway to study in detail potentially interesting events in progress, primarily with the aim of detecting extrasolar planets.

[37] In September 2020, astronomers using microlensing techniques reported the detection, for the first time, of an earth-mass rogue planet unbounded by any star, and free floating in the Milky Way galaxy.

The authors expect that many more will be found with future instruments, specifically the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope and the Vera C. Rubin Observatory.

Thus the event duration is determined by the time it takes the apparent motion of the lens in the sky to cover an angular distance

Since this observable is a degenerate function of the lens mass, distance, and velocity, we cannot determine these physical parameters from a single event.

The projected Einstein radius is related to the physical parameters of the lens and source by It is mathematically convenient to use the inverses of some of these quantities.

Although the Einstein angle is too small to be directly visible from a ground-based telescope, several techniques have been proposed to observe it.

The length of this deviation can be used to determine the time needed for the lens to cross the disk of the source star

If the lensing object is a star with a planet orbiting it, this is an extreme example of a binary lens event.

Follow-up groups then intensively monitor the ongoing event, hoping to get good coverage of the deviation if it occurs.

When the event is over, the light curve is compared to theoretical models to find the physical parameters of the system.

In October 2017, OGLE-2016-BLG-1190Lb, an extremely massive exoplanet (or possibly a brown dwarf), about 13.4 times the mass of Jupiter, was reported.

"Follow-up" groups often coordinate telescopes around the world to provide intensive coverage of select events.