Microscopic scale

One common microscopic length scale unit is the micrometre (also called a micron) (symbol: μm), which is one millionth of a metre.

[6] Over time the importance of measurements made at the microscopic scale grew, and an instrument named the Millionometre was developed by watch-making company owner Antoine LeCoultre in 1844.

[6] The British Association for the Advancement of Science committee incorporated the micro- prefix into the newly established CGS system in 1873.

[6] The micro- prefix was finally added to the official SI system in 1960, acknowledging measurements that were made at an even smaller level, denoting a factor of 10^-6.

[6] By convention, the microscopic scale also includes classes of objects that are most commonly too small to see but of which some members are large enough to be observed with the eye.

Such groups include the Cladocera, planktonic green algae of which Volvox is readily observable, and the protozoa of which stentor can be easily seen without aid.

[11] In the 1660s, Antonie van Leeuwenhoek devised a simple microscope utilising a single spherical lens mounted between two thin brass plates.

[16] When the monetary value of gems is determined, various professions in gemology require systematic observation of the microscopic physical and optical properties of gemstones.

As chemical properties such as water permeability, structural stability and heat resistance affect the performance of different materials used in pavement mixes, they are taken into consideration when building for roads according to the traffic, weather, supply and budget in that area.

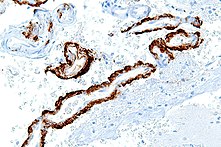

This is due to his significant contributions in the initial observation and documentation of unicellular organisms such as bacteria and spermatozoa, and microscopic human tissue such as muscle fibres and capillaries.

[22] Genetic manipulation of energy-regulating mitochondria under microscopic principles has also been found to extend organism lifespan, tackling age-associated issues in humans such as Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and multiple sclerosis.

[30] In conjunction with fluorescent tagging, molecular details in singular amyloid proteins can be studied through new light microscopy techniques, and their relation to Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

[32] Nanoscale imaging via atomic force microscopy has also been improved to allow a more precise observation of small amounts of complex objects, such as cell membranes.