Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The concept of the Middle Kingdom as one of three golden ages was coined in 1845 by German Egyptologist Baron von Bunsen, and its definition evolved significantly throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

[5] During Mentuhotep II's fourteenth regnal year, he took advantage of a revolt in the Thinite Nome to launch an attack on Herakleopolis, which met little resistance.

[4] After toppling the last rulers of the Tenth Dynasty, Mentuhotep began consolidating his power over all of Egypt, a process that he finished by his 39th regnal year.

[11] Despite this absence, his reign is attested from a few inscriptions in Wadi Hammamat that record expeditions to the Red Sea coast and to quarry stone for the royal monuments.

However, the Middle Kingdom was basically defensive in its military strategy, with fortifications built at the First Cataract of the Nile, in the Delta and across the Sinai Isthmus.

[25] During his reign, Senusret continued the practice of directly appointing nomarchs,[26] and undercut the autonomy of local priesthoods by building at cult centers throughout Egypt.

[38] Senusret eventually placed his pyramid at the site of el-Lahun, near the junction of the Nile and the Fayuum's major irrigation canal, the Bahr Yussef.

After his victories, Senusret built a series of massive forts throughout the country to establish the formal boundary between Egyptian conquests and unconquered Nubia at Semna.

[41] The personnel of these forts were charged to send frequent reports to the capital on the movements and activities of the local Medjay natives, some of which survive, revealing how tightly the Egyptians intended to control the southern border.

[42] Medjay were not allowed north of the border by ship, nor could they enter by land with their flocks, but they were permitted to travel to local forts to trade.

[48] Domestically, Senusret has been given credit for an administrative reform that put more power in the hands of appointees of the central government, instead of regional authorities.

[51] The power of the nomarchs seems to drop off permanently during his reign, which has been taken to indicate that the central government had finally suppressed them, though there is no record that Senusret ever took direct action against them.

[54] However, a reference to a year 39 on a fragment found in the construction debris of Senusret's mortuary temple has suggested the possibility of a long coregency with his son.

Mining camps in the Sinai, which had previously been used only by intermittent expeditions, were operated on a semi-permanent basis, as evidenced by the construction of houses, walls, and even local cemeteries.

Contemporary records of the Nile flood levels indicate that the end of the reign of Amenemhet III was dry, and crop failures may have helped to destabilize the dynasty.

[61] Sobekneferu ruled no more than four years,[62] and as she apparently had no heirs, when she died the Twelfth Dynasty came to a sudden end as did the Golden Age of the Middle Kingdom.

After the death of Sobeknefru, the throne may have passed to Sekhemre Khutawy Sobekhotep,[63][64] though in older studies Wegaf, who had previously been the Great Overseer of Troops,[65] was thought to have reigned next.

[67] The strongest king of this period, Neferhotep I, ruled for eleven years and maintained effective control of Upper Egypt, Nubia, and the Delta,[69] with the possible exceptions of Xois and Avaris.

[75] This basic form of administration continued throughout the Middle Kingdom, though there is some evidence of a major reform of the central government under Senusret III.

[26] Administrative documents and private stelae indicate a proliferation of new bureaucratic titles around this time, which have been taken as evidence of a larger central government.

[77] At roughly this time, the provincial aristocracy began building elaborate tombs for themselves, which have been taken as evidence of the wealth and power that these rulers had acquired as nomarchs.

Detlef Franke has argued that Senusret II adopted a policy of educating the sons of nomarchs in the capital and appointing them to government posts.

[83] The years of repeated high inundation levels correspond to the most prosperous period of the Middle Kingdom, which occurred during the reign of Amenemhat III.

These changes had an ideological purpose, as the Eleventh Dynasty kings were establishing a centralized state after the First Intermediate Period, and returning to the political ideals of the Old Kingdom.

Made of wood or cartonnage, the coffin was in the shape of a body wrapped in linen, wearing a beaded collar and a funerary mask.

Many examples of both of these types come from this period;[94] excavation at Abydos yielded over 2000 private stelae, ranging from excellent works to crude objects, although very few belonged to the elite.

This goal was communicated with the specific placement of information on the stone slabs similar to royal stelae (the owner's image, offering formula, inscriptions of names, lineage and titles).

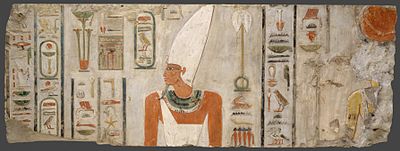

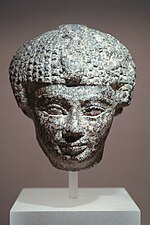

[99] The black granite seated statue of the king Amenemhat III to the right, above is a perfect example of male proportions and the squared grid system of this period.

Male figures had smaller heads in proportion to the rest of the body, narrow shoulders and waists, a high small of the back, and no muscled limbs.

[110] Old Kingdom texts served mainly to maintain the divine cults, preserve souls in the afterlife, and document accounts for practical uses in daily life.