Middlesex Canal

A number of innovations made the canal possible, including hydraulic cement, which was used to mortar its locks, and an ingenious floating towpath to span the Concord River.

The canal operated until 1851, when more efficient means of transportation of bulk goods, largely railroads, meant it was no longer competitive.

In the years after the American Revolutionary War, the young United States began a period of economic expansion away from the coast.

[2] Because of extremely poor roads, the cost of bringing goods such as lumber, ashes, grain, and fur to the coast could be quite high if water transport was unavailable.

Well aware that to stay independent the nation needed to grow strong and develop industries, the news from Europe rekindled a number of previously dropped canal or navigations projects and began discussions leading in the next decades to many others.

[4] Connecticut was believed to rise at similar elevations to the Merrimack River's, which could be reached by a string of streams, ponds, lakes, and manmade canals—if the canals were built.

A few true believers, but lesser socialites, needed a champion and pestered the Secretary of War, Henry Knox to ignite the project.

After the collapse of stocks in early 1793 put paid to a scheme to join the Charles River with Connecticut,[a] championed by Henry Knox, a group of leading Massachusetts businessmen and politicians led by States Attorney General James Sullivan proposed a connection from the Merrimack River to Boston Harbor in 1793.

Due to discrepancies in their results, Baldwin was authorized by the proprietors to travel to Philadelphia in an effort to secure the services of William Weston, a British engineer working on several canal and turnpike projects in Pennsylvania under contract to the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company.

A form of hydraulic cement (made in part from volcanic materials imported at great expense from Sint Eustatius in the West Indies) was used to make the stone locks watertight.

The whole system was complete in 1814,[10] and with just a few exceptions, overall came to operate with prices and regulations as set by the proprietors of the (main) Middlesex Canal.

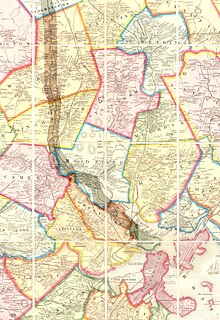

[12] The other direction, the canal ran from 'Middlesex Village' or East Chelmsford, Massachusetts (The Town of Chelmsford was later divided and East Chelmsford was renamed Lowell, Massachusetts, now the fourth most populous city in Massachusetts, primarily because of the Lowell textile industry spawned by the transportation infrastructure and water power along the Middlesex Canal and the Nashua and Merrimack Rivers), through several sparser settled Middlesex County outlier suburbs such as Billerica, and Tewksbury, then closer-in suburban towns with the lower course running towards Boston generally along water courses nearly paralleling the routes of MA 38 from Wilmington, thence in Woburn along the Aberjona River from Horn Pond through Winchester (or Waterfield) into the Mystic Lakes and down the Mystic River between Arlington and Somerville on the west bank and Medford along the east (left) bank, until the river and canal ran into the Boston Harbor tidewater in the Charlestown basin.

[14] These speed limits were set and maintained by the board of proprietors to prevent wakes from damaging the canal sides.

The Boston and Lowell Railroad (now a part of the MBTA Commuter Rail system) was built using the plans from the original surveys for the canal.

[15] Before the corporation was dissolved, the proprietors proposed to convert the canal into an aqueduct to bring drinking water to Boston, but this effort was unsuccessful.

Its owners converted the Pawtucket Canal for use as a power provider, leading to the growth of the mill businesses on its banks beginning in the 1820s.

The raising of the dam height at North Billerica was believed to cause flooding of seasonal hay meadows upstream and prompted numerous lawsuits against the canal proprietors.

Analysis done in the 20th century suggests that the dam, which still stands (although no longer at its greatest height), probably had a flooding effect on hay meadows as far as 25 miles up the watershed.

At North Billerica, where the canal met the Concord River at the millpond, a floating towpath was devised to handle the needs of crossing traffic patterns.

[18] Though significant portions of the Middlesex Canal are still visible, urban and suburban sprawl is quickly overcoming many of the remains.