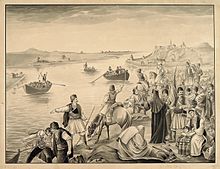

Migration of the Serbs (painting)

In 1689, Arsenije III, the Archbishop of Peć, incited Serbs in Kosovo, Macedonia and the Sandžak to revolt against the Ottoman Empire and support a Habsburg incursion into the Balkans.

[7] Leopold recognized Arsenije as the leader of Habsburg Serbs in both religious and secular affairs, and indicated that this power would be held by all future Archbishops.

[10] The showpiece of the art exhibit was The Conquest of the Carpathian Basin, a painting by Hungary's foremost history painter, Mihály Munkácsy, that was located in the Hungarian Parliament Building.

[17] The commission offered Jovanović the opportunity to make a name for himself as a serious history painter, given that the subject of the work was an event of international significance and the painting was to be displayed in a foreign capital.

[18] Notably, the Church asked the historian and Orthodox priest Ilarion Ruvarac to consult Jovanović on the historical details of the migration and accompany him on a visit to the monasteries of Fruška Gora, where the young artist examined a number of contemporary sources and objects from the time.

[18] The composition marked a significant departure for Jovanović, who up until that point had painted mostly Orientalist pieces as opposed to ones that depicted specific moments from Serbian history.

[2][c] Upon first seeing it, Georgije was displeased by Jovanović's depiction of the exodus, particularly the sight of sheep and wagons carrying women and children, saying it made the migrants look like "rabble on the run".

[29] The source of the Patriarch's displeasure lay in differing interpretations of what had originally caused the migration to take place; the Church maintained that Arsenije was simply heeding the call of the Holy Roman Emperor to head north.

Having studied Ruvarac's work, Jovanović came to hold the view that fear of Ottoman persecution, rather than the desire to protect the Habsburg frontier, had prompted the migrants to leave their homes.

[30] Jovanović duly took the painting back to his studio and altered it to the Patriarch's liking, removing the sheep, lumber wagons, and the woman and her infant son, putting stylized warriors in their place.

[34] While working on the copy that the Patriarch had commissioned, Jovanović began a second version of the painting, one that retained the woman and her child, the herd of sheep and the wagons carrying refugees.

[39] At the height of World War II, Jovanović created a third version on behalf of a Belgrade physician named Darinka Smodlaka, who requested that the figure of Monasterlija's wife bear her likeness.

In 1945, as the war neared its end, a wealthy Serbian merchant named Milenko Čavić commissioned a fourth and final version, incorrectly assuming that the others had been destroyed in the fighting.

[42] An allusion to it is made in Emir Kusturica's 1995 film Underground, in which war refugees are depicted marching towards Belgrade in similar fashion, following the German bombing of the city in April 1941.

Historian Katarina Todić observes that there are striking similarities between the painting and photographs of the Royal Serbian Army's retreat to the Adriatic coast during World War I.

[44] The journalist John Kifner describes Migration of the Serbs as a "Balkan equivalent to Washington Crossing the Delaware ... an instantly recognizable [icon] of the 500-year struggle against the Ottoman Turks.

"[38] Professor David A. Norris, a historian specializing in Serbian culture, calls Jovanović's approach "highly effective", and writes how the stoic attitude of the priests, warriors and peasants reminds the viewer of the historical significance of the migration.

"[45] Art historian Michele Facos describes the painting as a celebration of the Serbs' "valiant effort to defend Christian Europe against ... the Ottoman Turks.

[18] She writes that the Pančevo version "validates Jovanović as an insightful commentator on ... Balkan history", and is indicative of "the methodology and technical skill which had already brought him international acclaim.