Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

A professor at the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo in Valladolid, Hidalgo was influenced by Enlightenment ideas, which contributed to his ouster in 1792.

[5] On 16 September 1810 he gave the Cry of Dolores, a speech calling upon the people to protect the interest of their King Ferdinand VII, held captive during the Peninsular War, by revolting against the European-born Spaniards who had overthrown the Spanish Viceroy José de Iturrigaray.

[6] Hidalgo marched across Mexico and gathered an army of nearly 90,000 poor farmers and Mexican civilians who attacked Spanish Peninsular and Criollo elites.

Hidalgo's insurgent army accumulated initial victories on its way to Mexico City, but his troops ultimately lacked training and were poorly armed.

[8] At the age of fifteen Hidalgo was sent to Valladolid (now Morelia), Michoacán, to study at the Colegio de San Francisco Javier with the Jesuits, along with his brothers.

[18][20] From 1779 to 1792, he dedicated himself to teaching at the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo in Valladolid (now Morelia); it was "one of the most important educational centers of the viceroyalty.

He questioned the absolute authority of the Spanish king and challenged numerous ideas presented by the Church, including the power of the popes, the virgin birth, and clerical celibacy.

Allende was in charge of convincing Hidalgo to join his movement, since the priest of Dolores had very influential friends from all over the Bajío and even New Spain, such as Juan Antonio Riaño, mayor of Guanajuato, and Manuel Abad y Queipo, Bishop of Michoacán.

In 1803, aged 50, Hidalgo arrived in Dolores accompanied by his family that included a younger brother, a cousin, two half sisters, as well as María and their two children.

[19] After Hidalgo settled in Dolores, he turned over most of the clerical duties to one of his vicars, Francisco Iglesias, and devoted himself almost exclusively to commerce, intellectual pursuits and humanitarian activities.

These policies as well as exploitation of mixed race castas fostered animosity in Hidalgo towards the Peninsular-born Spaniards in Mexico.

[27] Fearing arrest,[19] Hidalgo ordered his brother Mauricio, as well as Ignacio Allende and Mariano Abasolo, to go with a number of other armed men to make the sheriff release prison inmates in Dolores on the night of 15 September 1810, setting eighty free.

On the morning of 16 September 1810, Hidalgo celebrated Mass, which was attended by about 300 people, including hacienda owners, local politicians, and Spaniards.

Many villagers that joined the insurgent army came to believe that Fernando VII himself commanded their loyalty to Hidalgo and the monarch was in New Spain personally directing the rebellion against the Viceroyalty.

Historian Eric Van Young believes that such ideas gave the movement supernatural and religious legitimacy that went as far as messianic expectation.

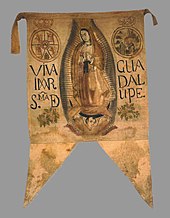

"[32] For the insurgents as a whole, the Virgin represented an intense and highly localized religious sensibility, invoked more to identify allies rather than create ideological alliances or a sense of nationalism.

When rioting ran through the city, Allende tried to break up violence by striking insurgents with the flat of his sword, which brought him a rebuke from Hidalgo.

Allende strongly protested these events and while Hidalgo agreed that they were heinous, he also stated that he understood the historical patterns that shaped such responses.

Hidalgo argued that the objective of the war was "to send the gachupines back to the motherland", accusing their greed and tyranny as leading to the temporal and spiritual degradation of Mexicans.

[30] The canon of the cathedral met Hidalgo and made him promise that the atrocities of San Miguel, Celaya and Guanajuato would not be repeated in Valladolid.

[20] On 19 October, Hidalgo left Valladolid for Mexico City after taking[clarification needed] 400,000 pesos from the cathedral to pay expenses.

[26] Hidalgo and his troops left the state of Michoacán and marched through the towns of Maravatio, Ixtlahuaca, and Toluca before stopping in the forested mountain area of Monte de las Cruces.

[18][19][37] After the Battle of Monte de las Cruces on 30 October 1810, Hidalgo had some 100,000 insurgents and was in a strategic position to attack Mexico City.

As the capital was guarded by some of the most trained soldiers in New Spain,[19] Hidalgo decided to turn away from Mexico City and move to the north[38] through Toluca and Ixtlahuaca[30] with a destination of Guadalajara.

[26] He initially occupied the city with lower-class support because Hidalgo promised to end slavery, tribute payment and taxes on alcohol and tobacco.

[26] After Guanajuato had been retaken by royalist forces, Bishop Manuel Abad y Queipo excommunicated Hidalgo and those following or helping him on 24 December 1810.

The Inquisition pronounced an edict against Hidalgo, charging him with denying that God punishes sins in this world, doubting the authenticity of the Bible, denouncing the popes and Church government, allowing Jews not to convert to Christianity, denying the perpetual virginity of Mary, preaching that there was no hell, and adopting Lutheran doctrine with regard to the Eucharist.

[19][26] At Hacienda de Pabellón, on 25 January 1811, near the city of Aguascalientes, Allende and other insurgent leaders took military command away from Hidalgo, blaming him for their defeats.

[37] Later, political movements would favor the more liberal Hidalgo over the conservative Iturbide, and 16 September 1810 became officially recognized as the day of Mexican independence.

David Alfaro Siqueiros was commissioned by San Nicolas McGinty University in Morelia to paint a mural for a celebration commemorating the 200th anniversary of Hidalgo's birth.