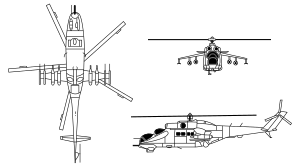

Mil Mi-24

Despite the opposition, Mil managed to persuade the defence minister's first deputy, Marshal Andrey A. Grechko, to convene an expert panel to look into the matter.

A number of changes were made at the insistence of the military, including the replacement of the 23 mm cannon with a rapid-fire heavy machine gun mounted in a chin turret, and the use of the 9K114 Shturm (AT-6 Spiral) anti-tank missile.

Also, a 12-degree anhedral was introduced to the wings to address the aircraft's tendency to Dutch roll at speeds in excess of 200 km/h (124 mph), and the Falanga missile pylons were moved from the fuselage to the wingtips.

[5][6] However, after the successful operation of the type in Syria it was decided to keep it in service and upgrade it with new electronics, sights, arms and night vision goggles.

Converting a UH-1 into a gunship meant stripping the entire passenger area to accommodate extra fuel and ammunition, and removing its troop transport capability.

[15] During the Afghan war, sources estimated the helicopter strength to be as much as 600 units, with up to 250 being Mi-24s,[16] whereas a (formerly secret) 1987 Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) report says that the number of Mi-24s in theatre increased from 85 in 1980 to 120 in 1985.

Fuel-air explosive bombs were also used in a few instances, though crews initially underestimated the sheer blast force of such weapons and were caught by the shock waves.

Gunship crews found the soldiers a concern and a distraction while being shot at, and preferred to fly lightly loaded anyway, especially given their operations from high ground altitudes in Afghanistan.

This weapon configuration still left the gunship blind to the direct rear, and Mil experimented with fitting a machine gun in the back of the fuselage, accessible to the gunner through a narrow crawl-way.

The Mujahideen learned to move mostly at night to avoid the gunships, and in response the Soviets trained their Mi-24 crews in night-fighting, dropping parachute flares to illuminate potential targets for attack.

The rebels' primary air-defence weapons early in the war were heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft cannons, though anything smaller than a 23 millimetre shell generally did not do much damage to an Mi-24.

[citation needed] The rebels also quickly began to use Soviet-made and US shoulder-launched, man-portable air-defense system (MANPADS) missiles such as the Strela and Redeye which had either been captured from the Soviets or their Afghan allies or were supplied from Western sources.

However this had the opposite effect of leaking all the exhaust gasses from the Mi-24's engines directly out the side of the aircraft and away from the helicopter's rotor wash, creating two massive sources of heat and ultraviolet radiation for the Stinger to lock onto.

After the introduction of the Stinger, doctrine changed to "nap of the earth" flying, where they approached very low to the ground and engaged more laterally, popping up to only about 200 ft (61 m) in order to aim rockets or cannons.

The crews called themselves "Mandatory Matrosovs", after a Soviet hero of World War II who threw himself across a German machine gun to let his comrades break through.

[18] Early in the war, Marat Tischenko, head of the Mil design bureau visited Afghanistan to see what the troops thought of his helicopters, and gunship crews put on several displays for him.

[18] Afghan Air Force Mi-24s in the hands of the ascendant Taliban gradually became inoperable, but a few flown by the Northern Alliance, which had Russian assistance and access to spares, remained operational up to the US invasion of Afghanistan in late 2001.

The Afghan pilots were trained by India and began live firing exercises in May 2009 in order to escort Mi-17 transport helicopters on operations in restive parts of the country.

Despite the conflict continuing, it has decreased in scale and is now limited to the jungle areas of Valley of Rivers Apurímac, Ene and Mantaro (VRAEM).

The only loss occurred on 7 February, when a FAP Mi-25 was downed after being hit in quick succession by at least two, probably three, 9K38 Igla shoulder-fired missiles during a low-altitude mission over the Cenepa valley.

[38] The Mi-24 was also heavily employed by the Iraqi Army during their invasion of Kuwait, although most were withdrawn by Saddam Hussein when it became apparent that they would be needed to help retain his grip on power in the aftermath of the war.

Major Caleb Nimmo, a United States Air Force Pilot, was the first American to fly the Mi-35 Hind, or any Russian helicopter, in combat.

Russian upgraded Mi-24PNs were credited for destroying 2 Georgian T-72SIM1 tanks, using guided missiles at night time, though some sources attribute those kills to Mil Mi-28.

[63] The Russian army did not lose any Mi-24s throughout the conflict, mainly because those helicopters were deployed to areas where Georgian air defence was not active,[63] though some were damaged by small arms fire and at least one Mi-24 was lost due to technical reasons.

[citation needed] Two Mi-35s operating for the pro-Gaddafi Libyan Air Force were destroyed on the ground on 26 March 2011 by French aircraft enforcing the no-fly zone.

[68] One Free Libyan Air Force Mi-25D (serial number 854, captured at the beginning of the revolt) violated the no-fly-zone on 9 April 2011 to strike loyalist positions in Ajdabiya.

Ukrainian army Mi-24P helicopters as part of the United Nations peacekeeping force fired four missiles at a pro-Gbagbo military camp in Ivory Coast's main city of Abidjan.

[vague][71] On 3 November 2016, a Russian Mi-35 made an emergency landing near Syria's Palmyra city, and was hit and destroyed, most likely by an unguided recoilless weapon after it touched down.

In early 2022, a base in Nushki and a check-post in Panjgur belonging to the Frontier Corps Balochistan Paramilitary were attacked by BLA terrorists.

The helicopter was hit by an Igla-S shoulder-launched missile fired by Azerbaijani soldiers while flying at low altitude and crashed, killing all three on board.