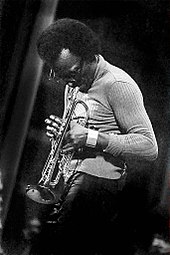

Miles Davis

During this period, he alternated between orchestral jazz collaborations with arranger Gil Evans, such as the Spanish music-influenced Sketches of Spain (1960), and band recordings, such as Milestones (1958) and Kind of Blue (1959).

[4] After adding saxophonist Wayne Shorter to his new quintet in 1964,[4] Davis led them on a series of more abstract recordings often composed by the band members, helping pioneer the post-bop genre with albums such as E.S.P.

During the 1970s, he experimented with rock, funk, African rhythms, emerging electronic music technology, and an ever-changing lineup of musicians, including keyboardist Joe Zawinul, drummer Al Foster, bassist Michael Henderson, and guitarist John McLaughlin.

[9] After a five-year retirement due to poor health, Davis resumed his career in the 1980s, employing younger musicians and pop sounds on albums such as The Man with the Horn (1981), You're Under Arrest (1985) and Tutu (1986).

He performed sold-out concerts worldwide, while branching out into visual arts, film, and television work, before his death in 1991 from the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia and respiratory failure.

[39] In August 1948, Davis declined an offer to join Duke Ellington's orchestra as he had entered rehearsals with a nine-piece band featuring baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and arrangements by Gil Evans, taking an active role on what soon became his own project.

[44][39] Evans' Manhattan apartment had become the meeting place for several young musicians and composers such as Davis, Roach, Lewis, and Mulligan who were unhappy with the increasingly virtuoso instrumental techniques that dominated bebop.

[45] These gatherings led to the formation of the Miles Davis Nonet, which included atypical modern jazz instruments such as French horn and tuba, leading to a thickly textured, almost orchestral sound.

[61] Blue Haze (1956), Bags' Groove (1957), Walkin' (1957), and Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants (1959) documented the evolution of his sound with the Harmon mute placed close to the microphone, and the use of more spacious and relaxed phrasing.

[a] In July 1955, Davis's fortunes improved considerably when he played at the Newport Jazz Festival, with a lineup of Monk, Heath, drummer Connie Kay, and horn players Zoot Sims and Gerry Mulligan.

The quintet contained Sonny Rollins on tenor saxophone, Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on double bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums.

Consisting of French jazz musicians Barney Wilen, Pierre Michelot, and René Urtreger, and American drummer Kenny Clarke, the group avoided a written score and instead improvised while they watched the film in a recording studio.

[98][99] In August 1959, during a break in a recording session at the Birdland nightclub in New York City, Davis was escorting a blonde-haired woman to a taxi outside the club when policeman Gerald Kilduff told him to "move on".

In 1964, Coleman was briefly replaced by saxophonist Sam Rivers (who recorded with Davis on Miles in Tokyo) until Wayne Shorter was persuaded to leave the Jazz Messengers.

In a Silent Way was recorded in a single studio session in February 1969, with Shorter, Hancock, Holland, and Williams alongside keyboardists Chick Corea and Joe Zawinul and guitarist John McLaughlin.

The album contained long compositions, some over twenty minutes, that more often than not, were constructed from several takes by Macero and Davis via splicing and tape loops amid epochal advances in multitrack recording technologies.

[120] Biographer Paul Tingen wrote, "Miles' newcomer status in this environment" led to "mixed audience reactions, often having to play for dramatically reduced fees, and enduring the 'sell-out' accusations from the jazz world", as well as being "attacked by sections of the black press for supposedly genuflecting to white culture".

Showcasing bassist Michael Henderson, who had replaced Holland in 1970, the album demonstrated that Davis's ensemble had transformed into a funk-oriented group while retaining the exploratory imperative of Bitches Brew.

"[132] After recording On the Corner, he assembled a group with Henderson, Mtume, Carlos Garnett, guitarist Reggie Lucas, organist Lonnie Liston Smith, tabla player Badal Roy, sitarist Khalil Balakrishna, and drummer Al Foster.

[142] In 1978, Davis asked fusion guitarist Larry Coryell to participate in sessions with keyboardists Masabumi Kikuchi and George Pavlis, bassist T. M. Stevens, and drummer Al Foster.

[151][152] Recordings from a mixture of dates from 1981, including from the Kix in Boston and Avery Fisher Hall, were released on We Want Miles,[153] which earned him a Grammy Award for Best Jazz Instrumental Performance by a Soloist.

[35] After taking part in the recording of the 1985 protest song "Sun City" as a member of Artists United Against Apartheid, Davis appeared on the instrumental "Don't Stop Me Now" by Toto for their album Fahrenheit (1986).

In November 1988 he was inducted into the Sovereign Military Order of Malta at a ceremony at the Alhambra Palace in Spain[165][166][167] (this was part of the reason for his daughter's decision to include the honorific "Sir" on his headstone).

[169] There were rumors of more poor health reported by the American magazine Star in its February 21, 1989, edition, which published a claim that Davis had contracted AIDS, prompting his manager Peter Shukat to issue a statement the following day.

[176] The show was followed by a concert billed as "Miles and Friends" at the Grande halle de la Villette in Paris two days later, with guest performances by musicians from throughout his career, including John McLaughlin, Herbie Hancock, and Joe Zawinul.

[203] A funeral service was held on October 5, 1991, at St. Peter's Lutheran Church on Lexington Avenue in New York City[204][205] that was attended by around 500 friends, family members, and musical acquaintances, with many fans standing in the rain.

[208] Late in his life, from the "electric period" onwards, Davis repeatedly explained his reasons for not wishing to perform his earlier works, such as Birth of the Cool or Kind of Blue.

"[210] Bill Evans, who played piano on Kind of Blue, said: "I would like to hear more of the consummate melodic master, but I feel that big business and his record company have had a corrupting influence on his material.

"[216] His approach, owing largely to the African-American performance tradition that focused on individual expression, emphatic interaction, and creative response to shifting contents, had a profound impact on generations of jazz musicians.

"[233] Also in the essay is a quote by music critic James Lincoln Collier who states that "if his influence was profound, the ultimate value of his work is another matter", and calls Davis an "adequate instrumentalist" but "not a great one".