Mines of Paris

[2] Much of north-western France spent much of its geological history as a submerged sea water coastline, but towards our era, and the formation of our continents as we know them, the then relatively flat area that would become the Paris region became increasingly elevated.

[3] The region of Paris has spent most of its geologic history under water, which is why it has such varied and important accumulations of sedimentary minerals, notably Lutetian Limestone.

[citation needed] Paris was the middle of a shoreline of bays and lagoons of still seawater, an environment perfect for the silica-based sea life abundant then.

After a period of land-sea alternation that brought layers of sand and low-quality calcaire grossier, the sea regressed again to return only occasionally to refill lagoons with seawater.

[citation needed] The result was stagnating pools of evaporating seawater; the salts of these, mixed with other organic matter and mineral deposits, crystallised into the calcium sulphate composition that is gypsum.

[citation needed] Paris began to take the form we know at present as huge rivers resulting from the melting of successive ice ages cut through millions of years of sediment, leaving only formations too elevated or too resistant to erosion.

Paris's hills of Montmartre and Belleville are the only places where gypsum remained, as the ancestor of the river Seine once flowed, almost along its present path, as wide as half the city, with many arms and tributaries.

Open-air quarrying became quite difficult and even costly when the desired minerals lay below the surface, as sometimes enormous amounts of earth and other unwanted deposits would have to be removed before it could be extracted.

Although it seems that well-mining method only began then, there is evidence that Romans used this technique to mine clay under Paris's Left Bank Montagne Sainte-Geneviève hill.

This method of burrowing was effective for the short-term, but over time the relatively soft mineral, subject to the elements and the earth's shifting, could erode or fissure, endangering the solidity of the mine.

Earlier mines closer to the city centre, when discovered, sometimes served a new purpose; when Louis XI donated the former Château Vauvert, a property which now forms the northern part of the Luxembourg Garden, to the Chartreuse order during 1259.

By the early 16th century, there were stone excavations operating around the present Jardin des Plantes, Boulevard St-Marcel, Val-de-Grâce hospital, southern Luxembourg (by then the Chartreuse Coventry), and in areas around the rue Vaugirard.

The Val de Grâce coventry and the Observatory, built from 1645 and 1672 respectively, were found to be undermined by immense caverns left by long-abandoned stone mines, reinforcing which consumed most of the budget reserved for both projects.

Another division of inspectors created about the same time, but directed by the Ministry of Finance, claimed the role of assuring the safety of the national roadways that were their jurisdiction.

Created officially on 24 April 1777,[8] the Inspection générale des carrières (IGC)[9] entered service on the same eve after a new collapse of the route de Fontainebleau (Avenue Denfert-Rochereau) outside of the barrière d'Enfer ("barrier of hell") city gateway.

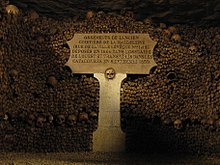

Human remains were progressively moved to a renovated section of the abandoned mines that would eventually become a full-fledged ossuary whose entrance is located on present day Place Denfert-Rochereau.