Minkowski's theorem

In mathematics, Minkowski's theorem is the statement that every convex set in

which is symmetric with respect to the origin and which has volume greater than

The theorem was proved by Hermann Minkowski in 1889 and became the foundation of the branch of number theory called the geometry of numbers.

and to any symmetric convex set with volume greater than

denotes the covolume of the lattice (the absolute value of the determinant of any of its bases).

Suppose that L is a lattice of determinant d(L) in the n-dimensional real vector space

that is symmetric with respect to the origin, meaning that if x is in S then −x is also in S. Minkowski's theorem states that if the volume of S is strictly greater than 2n d(L), then S must contain at least one lattice point other than the origin.

of all points with integer coefficients; its determinant is 1.

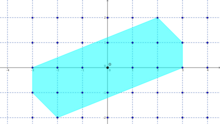

For n = 2, the theorem claims that a convex figure in the Euclidean plane symmetric about the origin and with area greater than 4 encloses at least one lattice point in addition to the origin.

The area bound is sharp: if S is the interior of the square with vertices (±1, ±1) then S is symmetric and convex, and has area 4, but the only lattice point it contains is the origin.

This example, showing that the bound of the theorem is sharp, generalizes to hypercubes in every dimension n. The following argument proves Minkowski's theorem for the specific case of

case: Consider the map Intuitively, this map cuts the plane into 2 by 2 squares, then stacks the squares on top of each other.

Clearly f (S) has area less than or equal to 4, because this set lies within a 2 by 2 square.

Assume for a contradiction that f could be injective, which means the pieces of S cut out by the squares stack up in a non-overlapping way.

That is not the case, so the assumption must be false: f is not injective, meaning that there exist at least two distinct points p1, p2 in S that are mapped by f to the same point: f (p1) = f (p2).

That is, the coordinates of the two points differ by two even integers.

Remarks: Minkowski's theorem gives an upper bound for the length of the shortest nonzero vector.

This result has applications in lattice cryptography and number theory.

Theorem (Minkowski's bound on the shortest vector): Let

contains a non-zero lattice point, which is a contradiction.

Remarks: The difficult implication in Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares can be proven using Minkowski's bound on the shortest vector.

is a quadratic residue modulo a prime

(Euler's Criterion) there is a square root of

, whence Minkowski's bound tells us that there is a nonzero

, and simple modular arithmetic shows that

Additionally, the lattice perspective gives a computationally efficient approach to Fermat's theorem on sums of squares:

Minkowski's theorem is also useful to prove Lagrange's four-square theorem, which states that every natural number can be written as the sum of the squares of four natural numbers.

Another application of Minkowski's theorem is the result that every class in the ideal class group of a number field K contains an integral ideal of norm not exceeding a certain bound, depending on K, called Minkowski's bound: the finiteness of the class number of an algebraic number field follows immediately.

The complexity of finding the point guaranteed by Minkowski's theorem, or the closely related Blichfeldt's theorem, have been studied from the perspective of TFNP search problems.

In particular, it is known that a computational analogue of Blichfeldt's theorem, a corollary of the proof of Minkowski's theorem, is PPP-complete.