Minstrel show

[12] Museums were set up to appeal to the low income audience, housing freak shows, wax sculptures, as well as exhibits of exoticism, mingled with magic, and necessarily live performance.

At the height of Rice's success, The Boston Post wrote, "The two most popular characters in the world at the present are [Queen] Victoria of the United Kingdom and Jump Jim Crow.

[20] Upper class houses at first limited the number of such acts they would show, but beginning in 1841, blackface performers frequently took to the stage at even the classy Park Theatre, much to the dismay of some patrons.

[22] Typical blackface acts of the period were short burlesques, often with mock Shakespearean titles like "Hamlet the Dainty", "Bad Breath, the Crane of Chowder", "Julius Sneezer" or "Dars-de-Money".

Nineteenth-century New York slaves shingle danced for spare change on their days off,[24] and musicians played what they claimed to be "Negro music" on so-called black instruments like the banjo.

[27] This coincided with the rise of groups struggling for workingman's nativism and pro-Southern causes, and faux black performances came to confirm pre-existing racist concepts and to establish new ones.

This suggested that the abuses against northern factory workers were a graver ill than the treatment of black slaves—or by a less class-conscious rhetoric of "productive" versus "unproductive" elements of society.

The term minstrel had previously been reserved for traveling white singing groups, but Emmett and company made it synonymous with blackface performance, and by using it, signalled that they were reaching out to a new, middle-class audience.

Life on the road entailed an "endless series of one-nighters, travel on accident-prone railroads, in poor housing subject to fires, in empty rooms that they had to convert into theaters, arrest on trumped up charges, exposed to deadly diseases, and managers and agents who skipped out with all the troupe's money.

[43] Adaptations of Uncle Tom's Cabin sprang up rapidly after its publication (all were unlicensed by its author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who refused to sell the theatrical rights for any sum).

[52] To balance the somber mood, minstrels put on patriotic numbers like "The Star-Spangled Banner", accompanied by depictions of scenes from American history that lionized figures like George Washington and Andrew Jackson.

[62] Small companies and amateurs carried the traditional minstrel show into the 20th century, now with an audience mostly in the rural South, while black-owned troupes continued traveling to more outlying areas like the West.

These companies emphasized that their ethnicity made them the only true delineators of black song and dance, with one advertisement describing a troupe as "SEVEN SLAVES just from Alabama, who are EARNING THEIR FREEDOM by giving concerts under the guidance of their Northern friends.

Troupes left town quickly after each performance, and some had so much trouble securing lodging that they hired whole trains or had custom sleeping cars built, complete with hidden compartments to hide in should things turn ugly.

In the early days of the minstrel show, this was often a skit set on a Southern plantation that usually included song-and-dance numbers and featured Sambo- and Mammy-type characters in slapstick situations.

The earliest minstrel characters took as their base popular white stage archetypes—frontiersmen, fishermen, hunters, and riverboatsmen whose depictions drew heavily from the tall tale—and added exaggerated blackface speech and makeup.

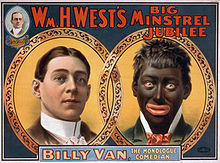

The blackface makeup and illustrations on programs and sheet music depicted them with huge eyeballs, very wide noses, and thick-lipped mouths that hung open or grinned foolishly; one character expressed his love for a woman with "lips so large a lover could not kiss them all at once".

Dandy characters often went by Zip Coon, after the song popularized by George Washington Dixon, although others had pretentious names like Count Julius Caesar Mars Napoleon Sinclair Brown.

Their clothing was a ludicrous parody of upper-class dress: coats with tails and padded shoulders, white gloves, monocles, fake mustaches, and gaudy watch chains.

These roles were almost always played by men in drag (most famously George Christy, Francis Leon and Barney Williams), even though American theater outside minstrelsy was filled with actresses at this time.

After the Civil War, the wench emerged as the most important specialist role in the minstrel troupe; men could alternately be titillated and disgusted, while women could admire the illusion and high fashion.

Actress Olive Logan commented that some actors were "marvelously well fitted by nature for it, having well-defined soprano voices, plump shoulders, beardless faces, and tiny hands and feet.

American Indians before the Civil War were usually depicted as innocent symbols of the pre-industrial world or as pitiable victims whose peaceful existence had been shattered by the encroachment of the white man.

[116]: 26 Minstrels caricatured East Asians by their strange language ("ching chang chung"), odd eating habits (dogs and cats), and propensity for wearing pigtails.

The minstrel show texts sometimes mixed black lore, such as stories about talking animals or slave tricksters, with humor from the region southwest of the Appalachians, itself a mixture of traditions from different races and cultures.

The black troupes sang the most authentic jubilees, while white companies inserted humorous verses and replaced religious themes with plantation imagery, often starring the old darky.

[138] Compounding the problem is the difficulty in ascertaining how much minstrel music was written by black composers, as the custom at the time was to sell all rights to a song to publishers or other performers.

[143] As late as 1942, as demonstrated in the Warner Bros. cartoon Fresh Hare, minstrel shows could be used as a gag (in this case, Elmer Fudd and Bugs Bunny leading a chorus of "Camptown Races") with the expectation, presumably, that audiences would get the reference.

[147] Many famous singers and actors gained their start in black minstrelsy, including W. C. Handy, Ida Cox, Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Ethel Waters, and Butterbeans and Susie.

Besides Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith, later musicians working for "the Foots" included Louis Jordan, Brownie McGhee and Rufus Thomas, and the company was still touring as late as 1950.