Missing women

[1] The phenomenon was first noted by the Indian Nobel Prize-winning economist Amartya Sen in an essay in The New York Review of Books in 1990,[2] and expanded upon in his subsequent academic work.

[2] Economists such as Nancy Qian and Seema Jayanchandran have found that a large part of the deficit in China and India is due to lower female wages and sex-selective abortion, or differential neglect.

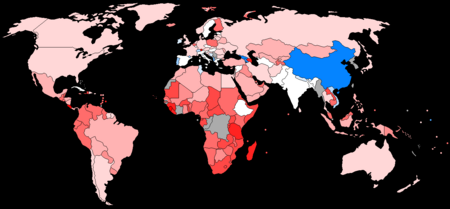

Using data from his Regional Model Life Tables, Coale found that the natural male-to-female sex ratio, accounting for different country fertility rates and circumstances, had an expected value of 1.059.

[25] He also noted a problem with the Regional Model Life Tables; they were based on countries with higher female mortality, which would bias Coale's numbers of missing women downwards.

[26] Klasen and Wink also noted that similar to both Sen's and Coale's results, Pakistan had the world's highest percentage of missing girls relative to its total pre-adult female population.

Das Gupta observed that the preference for boys and the resulting shortage of girls was more pronounced in the more highly developed Haryana and Punjab regions of India than in poorer areas.

The bias against girls is very evident among the relatively highly developed, middle-class dominated nations (Taiwan, South Korea, Singapore, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia) and the immigrant Asian communities in the United States and Britain.

[28] Some evidence suggests that in Asia, especially in Mainland China with its one-child policy, additional fertility behavior, infant deaths, and female birth information may be hidden or not reported.

[3] Sen argued that the disparity in sex ratio across eastern Asian countries like India, China, and Korea when compared to North America and Europe, as seen in 1992, could only be explained by deliberate nutritional and health deprivations against women and female children.

This is especially true in the medical care given to men and women, as well as prioritizing who gets food in less privileged families, leading to lower survival rates than if both genders were treated equally.

On the other hand, in Allahabad, India, women making cigarettes both gained an independent source of income and an increase in the community's view of their perceived contribution to the household.

[35] Sen suggests that in areas with high proportions of missing women, the care and nutrition female children receive are tied to the community's view of their importance.

Women are also often practically unable to inherit real estate, so a mother-widow will lose her family's (in reality her late husband's) plot of land and become indigent if she had had only daughters.

He concludes that these biases against women were so "entrenched" that even relative economic improvements in the lives of households have only enabled these parents a different avenue for rejecting their female children.

Sen then argued that instead of just increasing women's economic rights and opportunities outside the home a greater emphasis needed to be placed on raising consciousness to eradicate the strong biases against female children.

Das Gupta finds that in South Korea, the male-to-female sex ratio spiked from 1.07 to 1.15 between the 1980s and 1990s because of the rising prevalence of ultrasound technology for the use of sex-selective abortions, but declined afterwards between 1990 and 2000 because of increasing modernization, education, and economic opportunities.

[7] In her PhD dissertation at Harvard, Emily Oster argued that Sen's hypothesis did not take account of the different rates of prevalence of the Hepatitis B virus between Asia and other parts of the world.

They are, however, consistent with Sen's contention that it is purposeful human action – in the form of selective abortion and perhaps even infanticide and female infant neglect – that is the cause of the skewed gender ratio.

[10] Their findings for mainland China also attribute missing women of older ages to cardiovascular and other non-communicable diseases, accounting for a large portion of excess female deaths.

The high prevalence of HIV/AIDS seems to suggest, according to Anderson and Ray, an imbalance in women's access to healthcare as well as different attitudes about sexual and cultural norms.

[45][47] This school of scholars support their alternate hypothesis with historical data when modern sex-selection technologies were unavailable, as well as birth sex ratio in sub-regions, and various ethnic groups of developed economies.

[15] While underweight female babies are at risk for continuing undernourishment, ironically, Sen points out that even decades after birth, "men suffer disproportionately more from cardiovascular diseases.

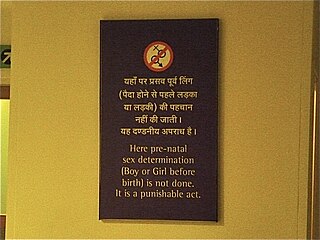

[60] Since the advent of sex-selective abortions via ultrasound and other medical procedures in the 1980s, the gender discriminations that have caused the “missing women” have simultaneously produced cohorts of excess men.

[61] To combat runaway sex-ratio disparity, Hesketh recommends government policy to intervene by making sex selective abortion illegal and promoting awareness to fight son preference paradigms.

According to Chung and Das Gupta rapid economic growth and development in South Korea has led to a sweeping change in social attitudes and reduced the preference for sons.

[62] Das Gupta, Chung, and Shuzhuo conclude that it is possible that China and India will experience a similar reversal in trend towards normal sex ratio in the near future if their rapid economic development, combined with policies that seek to promote gender equality, continue.

[2] Researchers argue that the prevalence of "missing women" is often intertwined with a society's culture and history, and as a result, it is difficult to create broad policy solutions.

They found that as women participated more in the work force and maintained their unpaid labor the sex ratio disparity grew, contrary to Sen's original prediction.

The OECD includes "missing women" as a measure under the Son preference parameter of its Social Inclusion and Gender Index, bringing awareness to it as an issue.

[16] On the other hand, they argue that culturally instituted inequities such as India's caste system, which stratifies its society, prevent the spread of more progressive ideas, and as a result, cause a higher prevalence of missing women.

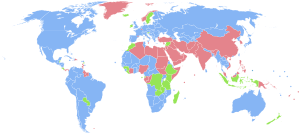

|

Countries with more

males

than females

Countries with the

same

number of males and females (accounting that the ratio has 3

significant figures

, i.e., 1.00 males to 1.00 females)

Countries with more

females

than males

No data

|