Modular elliptic curve

In the 1950s and 1960s a connection between elliptic curves and modular forms was conjectured by the Japanese mathematician Goro Shimura based on ideas posed by Yutaka Taniyama.

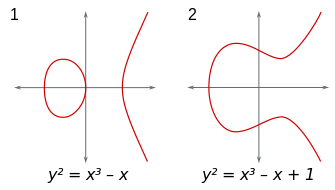

On a separate branch of development, in the late 1960s, Yves Hellegouarch came up with the idea of associating solutions (a,b,c) of Fermat's equation with a completely different mathematical object: an elliptic curve.

[2] For example, Wiles' ex-supervisor John Coates states that it seemed "impossible to actually prove",[3] and Ken Ribet considered himself "one of the vast majority of people who believed [it] was completely inaccessible".

[4] Wiles first announced his proof on Wednesday June 23, 1993, at a lecture in Cambridge entitled "Elliptic Curves and Galois Representations.

One year later, on Monday September 19, 1994, in what he would call "the most important moment of [his] working life," Wiles stumbled upon a revelation, "so indescribably beautiful... so simple and so elegant," that allowed him to correct the proof to the satisfaction of the mathematical community.

It also uses standard constructions of modern algebraic geometry, such as the category of schemes and Iwasawa theory, and other 20th-century techniques not available to Fermat.

The modularity theorem implies a closely related analytic statement: to an elliptic curve E over Q we may attach a corresponding L-series.

The function obtained in this way is, remarkably, a cusp form of weight two and level N and is also an eigenform (an eigenvector of all Hecke operators); this is the Hasse–Weil conjecture, which follows from the modularity theorem.

The Jacobian of the modular curve can (up to isogeny) be written as a product of irreducible Abelian varieties, corresponding to Hecke eigenforms of weight 2.