Mohenjo-daro

'Mound of the Dead Men'; Urdu: موئن جو دڑو [muˑənⁱ dʑoˑ d̪əɽoˑ]) is an archaeological site in Larkana District, Sindh, Pakistan.

[2][3] With an estimated population of at least 40,000 people, Mohenjo-daro prospered for several centuries, but by c. 1700 BCE had been abandoned,[4] along with other large cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

[citation needed] Mohenjo-daro may also have been a point of diffusion for the clade of the domesticated chicken found in Africa, Western Asia, Europe and the Americas.

[5] A dry core drilling conducted in 2015 by Pakistan's National Fund for Mohenjo-daro revealed that the site is larger than the unearthed area.

[20] The sheer size of the city, and its provision of public buildings and facilities, suggests a high level of social organization.

However, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer noted the complete lack of evidence for grain at the "granary", which, he argued, might therefore be better termed a "Great Hall" of uncertain function.

[citation needed] Mohenjo-daro had no series of city walls, but was fortified with guard towers to the west of the main settlement, and defensive fortifications to the south.

Considering these fortifications and the structure of other major Indus valley cities like Harappa, it is postulated that Mohenjo-daro was an administrative center.

Both Harappa and Mohenjo-daro share relatively the same architectural layout, and were generally not heavily fortified like other Indus Valley sites.

The location of Mohenjo-daro was built in a relatively short period of time, with the water supply system and wells being some of the first planned constructions.

[30] For some archaeologists, it was believed that a final flood that helped engulf the city in a sea of mud brought about the abandonment of the site.

[31] Instead of a mud flood wiping part of the city out in one fell swoop, Possehl coined the possibility of constant mini-floods throughout the year, paired with the land being worn out by crops, pastures, and resources for bricks and pottery spelled the downfall of the site.

[32] Numerous objects found in excavation include seated and standing figures, copper and stone tools, carved seals, balance-scales and weights, gold and jasper jewellery, and children's toys.

[34] Many bronze and copper pieces, such as figurines and bowls, have been recovered from the site, showing that the inhabitants of Mohenjo-daro understood how to utilize the lost wax technique.

Eventually an agreement was reached, whereby the finds, totalling some 12,000 objects (most sherds of pottery), were split equally between the countries; in some cases this was taken very literally, with some necklaces and girdles having their beads separated into two piles.

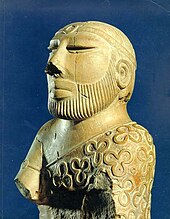

In the case of the "two most celebrated sculpted figures", Pakistan asked for and received the Priest-king, while India retained the much smaller Dancing Girl,[40] and also the Pashupati seal.

In 1939, a small representative group of artefacts excavated at the site was transferred to the British Museum by the Director-General of the Archaeological Survey of India.

[41] Discovered by John Marshall in 1931, the idol appears to mimic certain characteristics that match the Mother Goddess belief common in many early Near East civilisations.

[42] Sculptures and figurines depicting women have been observed as part of Harappan culture and religion, as multiple female pieces were recovered from Marshall's archaeological digs.

A bronze statuette dubbed the "Dancing Girl", 10.5 centimetres (4.1 in) high[43] and about 4,500 years old, was found in 'HR area' of Mohenjo-daro in 1926; it is now in the National Museum, New Delhi.

[43] In 1973, British archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler described the item as his favorite statuette:She's about fifteen years old I should think, not more, but she stands there with bangles all the way up her arm and nothing else on.

The statue led to two important discoveries about the civilization: first, that they knew metal blending, casting and other sophisticated methods of working with ore, and secondly that entertainment, especially dance, was part of the culture.

The sculpture is 17.5 centimetres (6.9 in) tall, and shows a neatly bearded man with pierced earlobes and a fillet around his head, possibly all that is left of a once-elaborate hairstyle or head-dress; his hair is combed back.

[46] The Mohenjo-Daro ruler is divided into units corresponding to 34 millimetres (1.32 in) and these are further marked in decimal subdivisions with great accuracy, to within 0.13 mm (0.005 in).

[47] An initial agreement to fund restoration was agreed through the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Paris on 27 May 1980.

Contributions were made by a number of other countries to the project: Preservation work for Mohenjo-daro was suspended in December 1996 after funding from the Pakistani government and international organizations stopped.