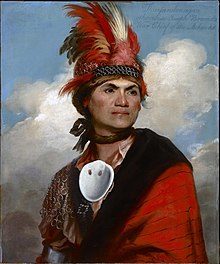

Molly Brant

Living in the Province of New York, she was the consort of Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent of Indian Affairs, with whom she had eight children.

In recognition of her service to the Crown, the British government gave Brant a pension and compensated her for her wartime losses, including a grant of land.

[2] Named Mary, but commonly known as "Molly", she was born around 1736, possibly in the Mohawk village of Canajoharie, or perhaps further west in the Ohio Country.

[4] Brant may have been the child named Mary who was christened at the chapel at Fort Hunter, near the Lower Castle, another Mohawk village, on April 13, 1735.

At the time of the American Revolutionary War, they lived primarily in the Mohawk River valley in what is now upstate New York, west of what developed as colonial Albany and Schenectady.

At some point, either before or after her birth, Molly's family moved west to the Ohio Country, which the Iroquois had reserved as a hunting ground since the late 17th century.

[7][Note 1] Possibly to reinforce their connection to Brant Kanagaradunkwa, who was a prominent leader, Molly and Joseph took their stepfather's name as a surname, which was unusual for that time.

[2] Molly Brant was raised in a Mohawk culture that had absorbed some influences from their Dutch and English trading partners during a period of extended contact.

[9] In 1754, Molly accompanied her stepfather and a delegation of Mohawk elders to Philadelphia, where the men were to discuss a fraudulent land sale with colonial leaders.

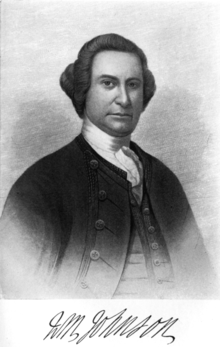

[11] When General Sir William Johnson, Superintendent for Northern Indian Affairs, visited Canajoharie, he always stayed at the house of his friend, Molly's stepfather Brant Kanagaradunkwa.

Brant played a prominent role in the life of Fort Johnson, managing household purchases, from expensive china to sewing supplies.

[15] They included the following:[16] In Johnson's will, Molly is referred to as his "housekeeper", which at the time meant that she ran the household, served as hostess, and supervised the female servants and slaves.

"[16] Johnson and Brant's relationship was public; she received gifts and thank-you notes from prominent visitors such as Lord Adam Gordon.

[26] A turning point came in 1777 when British forces invaded New York from Canada and laid siege to Patriots in Fort Stanwix.

In August, when Brant learned that a large body of Patriot militia was on its way to relieve the fort, she sent Mohawk runners to alert the British commander of the danger.

[26] This information enabled a British, Mohawk, and Seneca force to ambush the Patriots and their Oneida allies in the Battle of Oriskany.

Brant criticized Sayenqueraghta's advice, invoking the memory of Sir William to convince the council to remain loyal to the Crown.

[21] In late 1777, Brant relocated to Fort Niagara at the request of Major John Butler, who wanted to make use of her influence among the Iroquois.

[16][29][28] At Niagara, Brant worked as an intermediary between the British and the Iroquois, rendering, according to Graymont, "inestimable assistance there as a diplomat and stateswoman".

[16] Meanwhile, in November 1777 Brant's son Peter Johnson was killed in the Philadelphia campaign while serving in the British 26th Regiment of Foot.

[34] Throughout the war, Brant played important roles as a negotiator, mediator, liaison, and advocate for Mohawk and Iroquois peoples at Fort Niagara, Montreal, and Carleton Island.

[35] Hoping to make use of her influence, the United States offered Brant compensation if she would return with her family to the Mohawk Valley, but she refused.

[1] Brant was long ignored or disparaged by historians of the United States, but scholarly interest in her increased in the late 20th century with a better understanding of her role and influence in Iroquois society.

[42] The Johnson Hall State Historic Site in New York includes presentation and interpretation of her public and private roles for visitors.

[43] According to Feister and Pulis, "She made choices for which she is sometimes criticized today; some have seen her as having played a large part in the loss of Iroquois land in New York State.

"[44] But like many of the male leaders, Brant believed that the Mohawk and other Iroquois nations' best chance of survival lay with the British.

The commemoration began with a service at St. George's Cathedral, a traditional Mohawk tobacco burning and a wreath-laying ceremony at St. Paul's Anglican Church, and a reception at Rideaucrest.

[47] The Molly Brant One Woman Opera, composed by Augusta Cecconi-Bates, was first performed at St. George's Cathedral in Kingston on April 25, 2003, under the aegis of the Cataraqui Archaeological Research Foundation.