Mongol campaign against the Nizaris

Hülegü's campaign began with attacks on strongholds in Quhistan and Qumis amidst intensified internal dissensions among Nizari leaders under Imam Muhammad III of Alamut whose policy was fighting against the Mongols.

His successor, Rukn al-Din Khurshah, began a long series of negotiations in face of the implacable Mongol advance.

The main primary source is the Tarikh-i Jahangushay written by the historian Ata-Malik Juvayni, who was present in the campaign as an official under Hulegu.

[2] In 1192 or 1193, Rashid al-Din Sinan had been succeeded by the Persian da'i Nasr al-Ajami, who restored Alamut suzerainty over the Nizaris in Syria.

[3] After the Mongol invasion of Persia, many Sunni and Shia Muslims (including the prominent scholar al-Tusi) had taken refuge with the Nizaris of Quhistan.

The governor (muhtasham) of Quhistan was Nasir al-Din Abu al-Fath Abd al-Rahim ibn Abi Mansur.

But the latter dismissed them, and soon dispatched reinforcements under Eljigidei to Persia, instructing him to dedicate one-fifth of the forces there to reduce rebellious territories, beginning with the Nizari state.

In 1252, Möngke entrusted the mission of conquering the rest of Western Asia to his brother Hülegü, with the highest priority being the conquest of the Nizari state and the Abbasid Caliphate.

[9][10][11] In March 1253, Hülegü's advance guard under the command of Kitbuqa crossed the Oxus (Amu Darya) with 12,000 men (one tümen plus two mingghans under Köke Ilgei).

Kitbuqa left an army under amir Büri to besiege Gerdkuh, and himself attacked the nearby Mihrin (Mehrnegar) castle and Shah (in Qasran?).

[16][18][19] In October 1253, Hülegü left his orda in Mongolia and began his march with a tümen at a leisurely pace and increased his number in his way.

[15][20][16] He was accompanied by two of his ten sons, Abaqa and Yoshmut,[19] his brother Subedei, who died en route,[21] his wives Öljei and Yisut, and his stepmother Doquz.

[18][16] Gerdkuh was on the verge of falling due to an outbreak of cholera, but unlike Lambsar, it survived the epidemic and was saved by the arrival of reinforcements from Alamut sent by the Imam Ala al-Din Muhammad in the summer of 1254.

[20] He then made Kish (Shahrisabz) his temporary headquarters, and sent messengers to the local Mongol and non-Mongol rulers in Persia, announcing his presence as the Great Khan's viceroy and asking for assistance against the Nizaris, with the punishment of refusal being their utter destruction.

[24] All of the rulers of Rum (Anatolia), Fars, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Arran, Shirvan, Georgia, and supposedly also Armenia, acknowledged their service with many gifts.

[21] Hülegü had with him a thousand squads of siege engineers (probably north Chinese, Khitan and Muslim) skilled in the use of mangonels and naphtha.

Khurshah was at the Maymun-Diz fortress and was apparently playing for time; by resisting longer, the arrival of winter could have stopped the Mongol campaigning.

He sent his vizier Kayqubad; they met the Mongols in Firuzkuh and offered the surrender of all strongholds except Alamut and Lambsar, and again asked for a year's delay for Khurshah to visit Hülegü in person.

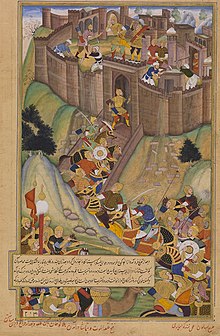

[16] Maymun-Diz could have been attacked by mangonels; that was not the case with Alamut, Nevisar Shah, Lambsar and Gerdkuh, all of which were on top of high peaks.

The Mongols then used heavier siege engines hurling javelins dipped in burning pitch and set up additional mangonels all around the fortifications.

A small part of the garrison refused to surrender and fought in a last stand in a high domed building in the fortress; they were defeated and slaughtered after three days.

All castles (around forty) subsequently capitulated, except Alamut (under sipahsalar Muqaddam al-Din Muhammad Mubariz) and Lambsar, possibly because their commanders thought the Imam had issued orders under duress and was practicing a sort of taqiyya.

Despite the small size of the fortress and its garrison, Alamut was stone-built (unlike Maymun-Diz), well-provisioned, and featured a reliable water supply.

He also picked Hasan Sabbah's biography, Sargudhasht-i Bābā Sayyidinā (Persian: سرگذشت بابا سیدنا), which interested him, but he claims he burnt it after reading it.

[16] As his position became intolerable, Khurshah asked Hülegü to be allowed to go meet Möngke in Mongolia, promising that he would persuade the remaining Ismaili fortresses to surrender.

Möngke rebuked him after visiting him in Karakoram, Mongolia, due to his failure to hand over Lambsar and Gerdkuh, and ordered his return to his homeland.

[16][4] Khurshah's relatives who were kept at Qazvin were killed by Qaraqai Bitikchi, while Ötegü-China summoned the Nizaris of Quhistan to gatherings and slaughtered about 12,000 people.

Little is known about the history of the Ismailis in this stage, until two centuries later, when they again began to grow as scattered communities under regional da'is in Iran, Afghanistan, Badakhshan, Syria, and India.

The Mamluks may have employed Nizari fedais against their own enemies, notably the attempted assassination of the Crusader Prince Edward of England in 1271.