Mongol incursions in the Holy Roman Empire

A crusading army under the command of King Conrad IV of Germany mustered on 1 July 1241, but was disbanded a few weeks after setting out because the danger had passed.

[7] In his Chronica majora, Matthew of Paris records that rumours about the Mongols had spread into the empire by 1238, for which reason the fishmongers of Frisia were unwilling to go to England.

[5] He is also the source for the rumour that the Mongols were the Lost Tribes of Israel and were assisted by Jews smuggling arms out of Germany in wine barrels.

[12][13] At the same time, Béla sent a letter to King Louis IX of France requesting help and another to the Emperor Frederick offering to submit Hungary to the Empire in exchange for military support.

[15] The emperor responded in a letter that he could not assist until his quarrel with the pope was resolved and directed the Hungarian king to request aid from Conrad IV, who had formally been ruling Germany since 1237.

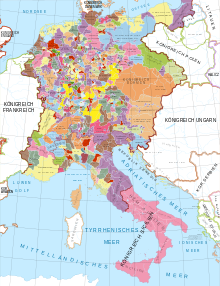

[20] Following their victory over Duke Henry of Silesia in the Battle of Legnica on 9 April 1241, Mongol detachments entered the marches of Meissen and Lusatia in eastern Germany, advancing as far as the Elbe.

[22] According to Wenceslaus, who wrote letters to the princes of Germany informing them of the Mongols' progress, they were moving at a pace of 40 miles (64 km) per day away from the Bohemian border.

[30] The Franciscan vice-minister in Bohemia, Jordan of Giano,[b] who wrote letters from Prague while the Mongols were in Moravia, indicates that they had passed through the Moravian Gate before 9 May.

[35] The only evidence relating to a specific place is a charter of 1247 in which Margrave Ottokar gave the city of Opava some privileges because of the damage the Mongols had caused in the region.

[21] The Mongols were probably in Austria as late as July,[39] although already in that month Duke Frederick II was occupying the Hungarian counties that Béla IV had pawned him.

[14] In a letter to Conrad IV dated 13 June 1241, he reports on the damage the Mongols inflicted on Austria and estimates that he killed 300 of them on the banks of the Morava.

[40][41] A week later, in a letter to Bishop Henry of Constance dated 22 or 23 June 1241, Frederick revises his estimate of casualties upwards to 700 and puts his own dead at 100.

[50] Ivo credits the prince of Dalmatia—possibly Duke Otto II of Merania—with capturing eight of the enemy, including an Englishman who had served the Mongols for years and under interrogation revealed much that was not previously known in the West.

[56] A Mongol army entered western Hungary, eastern Austria and southern Moravia again in late December 1241, as recorded in a letter dated 4 January 1242 from a Benedictine abbot in Vienna, quoted by Matthew of Paris.

The historian Peter Jackson agrees with the Templar master that had the Mongols launched a serious invasion of the Empire in the spring of 1241, "it is unlikely that they would have encountered coordinated opposition.

[58] A princely assembly was held at Merseburg on 22 April to raise troops and coordinate efforts, according to the Sächsische Weltchronik and the Annales breves Wormatienses.

[f] There is no record of who attended,[g] but Duke Albert of Saxony and Bishop Conrad of Meissen had mustered an army and joined Wenceslaus at Königstein by 7 May.

[59] In late April, another assembly was held at Herford (or perhaps Erfurt) under the presidency of Archbishop Siegfried of Mainz, then acting regent in Germany, but it did not lead to the formation of an army.

[59] The ongoing quarrel between the excommunicated emperor and the pope hampered the imperial response to the arrival of the Mongols on the empire's eastern border.

[60] In Italy, Filippo da Pistoia, the bishop of Ferrara, circulated a letter he claimed to have received showing that the Emperor Frederick II had sent envoys to the Mongols and was in league with them.

[27] On 20 June in Faenza, the emperor issued the Encyclica contra Tartaros, an encyclical letter announcing the fall of Kiev, the invasion of Hungary and the threat to Germany, and requesting each Christian nation to devote its proper quota of men and arms to the defence of Christendom.

[h] On 3 July, Frederick II addressed a letter to his brother-in-law, King Henry III of England, informing him of the Mongol threat.

The emperor had seemingly just received letters from Conrad IV, the kings of Hungary and Bohemia and the dukes of Austria and Bavaria informing him of the Mongols' progress.

[68] On the advice of the secular princes, Archbishop Siegfried promulgated instructions for the Dominicans and Franciscans to preach a crusade against the Mongols on 25 April, after the assembly in Herford.

[73] On 19 June, referring to the letter he had received from Duke Frederick, he issued a formal indulgence for the defence of Germany and Bohemia, as he had three days earlier for Hungary.

[j] Despite the lack of contemporary evidence for a major German victory over the Mongols, the rumour that they had received such a check spread as far as Egypt, Armenia and Muslim Spain.

The Flor des estoires de la terre d'Orient of Hayton of Corycus states that the duke of Austria and the king of Bohemia defeated the Mongols on the Danube and Batu drowned.

[80] Matthew of Paris claims that Conrad IV and his brother, King Enzo of Sardinia, defeated a Mongol army on the banks of the river Delpheos (possibly the Dnieper).

[81] In the Czech Chronicle of Václav Hájek (1541), the Hungarian victory before Olomouc is transformed into a defeat and the leader of the Moravians is Jaroslav of Sternberg [cz].

Jaroslav of Sternberg was transformed into a national hero who defeated the Mongols before Olomouc and killed Baidar in the Dvůr Králové manuscript literary hoax in the 19th century.