Monkland Canal

Maintaining an adequate water supply was a problem, and later an inclined plane was built at Blackhill, in which barges were let down and hauled up, floating in caissons that ran on rails.

Additionally, the Gartsherrie branch of the canal, which passes through Summerlee Heritage Park, was designated a scheduled monument by Historic Environment Scotland in 2013.

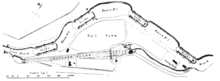

[4] (Gartsherrie Burn ran north to south between the alignment of the two present-day railways that cross Bank Street; it was culverted when the area was later developed.)

The canal then heads west again, with a short northerly spur serving coal pits at Drumpellier, continuing under the present-day railway line, and under the Cuilhill Road bridge.

[5] A short branch was formed off the cut off junction to serve industrial premises in the area between the present Royston Road and Charles Street.

Available coal was mined in Lanarkshire, but, before proper roads were built, the cost of transport by horse and cart was a significant factor.

[6] The inventor and engineer James Watt said later that Monklands was "a country full of level free coals of good quality, in the hands of many proprietors, who sell them at present at 6d per cart of 7 cwt at the pit".

The Town Council of Glasgow agreed to subscribe £500, with a complicated precondition designed to prevent the coalowners forming a cartel to keep prices high.

[4] Watt preferred engineering design to managing the works: "Nothing is more contrary to my disposition than bustling and bargaining with mankind:--yet that is the life I now constantly lead.

Smeaton "pointed out that the depth of the canal could with advantage be increased to four feet ... without any additional excavation, and the General Meeting of the proprietors three days later agreed to this".

It seems likely that the initial money subscribed had run out without the canal being completed, and the financial climate made it difficult to continue, and that the company terminated Watt's employment.

Not much coal seems to have traversed the part of the canal that was open, so that quite apart from the shortage of capital to continue construction, the company was making an operating loss and was unable to pay its debts.

Miller tells the tale: ... for many years, the revenue derived was so trifling, compared with the great outlay of capital, that the shareholders almost despaired of its ever proving a profitable investment.

It is said that in 1805, when the annual meeting of shareholders took place, presided over by Mr Colt of Gartsherrie, at the conclusion, murmurs of dissatisfaction prevailed among the members at the very cheerless report.

[23] Returning to 1786, the proprietors of the canal realised that the Blackhill discontinuity had now to be overcome; moreover the best coalfields lay a couple of miles east of Sheepford.

The Monkland Company was obliged to keep its canal open as a watercourse, this being a first charge on it; and it was authorised to extend from Sheepford "to the Calder at or near Faskine or Woodhill Mill and to erect sufficient locks to make it navigable".

In 1820 the city of Glasgow was consuming "half a million tons of coal a year, almost all of it subject to the high tolls on the Monkland Canal".

[14] In 1846 Lewis reported: "An extensive basin was lately formed at Dundyvan, for the shipment of coal and iron by the canal from the Wishaw and Coltness and the Monkland and Kirkintilloch railways; and boats to Glasgow take goods and passengers twice every day.

"[15][32] Fullarton, publishing in 1846 says that "a very large sum has recently been expended by the company in the formation of new works, [which has included] additional reservoirs in the parish of Shotts, all uniting in the river Calder which flows into the canal at Woodhall, near Holytown, thereby insuring an abundant supply of water at all times".

The canal had originally been planned to stop short of central Glasgow, to avoid descending to the lower level there; a causeway was authorised, envisaging horse and cart haulage to the city, but it was not built.

The conveyance of coal, iron ore and machinery from the canal down to the quays resulted in a huge and inconvenient cartage traffic through the city streets; this "added a cost equivalent to ten miles [16 km] carriage on a railway", and of course involved a trans-shipment.

[33] Although the trading position was buoyant in the mid-1840s, as railways developed and improved their own services, the canal lost traffic heavily as the years passed.

The limited financial and technical resources available at this time (Watt had long since departed) suggest that this might have been simply a sloping causeway on which boxes of coals were dragged down loaded, and back up empty.

[40] However, after consideration of the technical alternatives, it was "resolved to rebuild the two old upper locks and to build two new lower ones, so as to give an entire double set, which was done in 1841".

When a descent was about to start, the gates were closed and about 50 cubic feet (1,400 L) of water from the space between was lost; it was pumped back to the upper reach.

However, it proved possible to operate one side of the incline, of course without the benefit of the counterbalancing, the steam engines taking the whole of the load of the ascending caisson.

This was done for the rest of the autumn; even with this serious temporary limitation, 30 boats a day were taken up, a total of 1124 including a few descending, until the beginning of November when the dry season ended.

c. lxiii) on 4 July 1843 to construct a railway to connect pits at Bankhead to the canal at Cuilhill Gullet, a distance of just under two miles [3 km].

[45] The land falls considerably from Cuilhill to Braehead – about 100 feet in a mile (20 metres in 1 km) – and Cobb shows two inclined planes in this short section of railway.

There is a track from the basin to the prison shown on the later map[51] In the mid-1980s, the canal was stocked with Carp, Roach, Bream, Tench, Perch and some other species.