Monopoly on violence

While the monopoly on violence as the defining conception of the state was first described in sociology by Max Weber in his essay Politics as a Vocation (1919),[1] the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force is a core concept of modern public law, which goes back to French jurist and political philosopher Jean Bodin's 1576 work Les Six livres de la République and English philosopher Thomas Hobbes's 1651 book Leviathan.

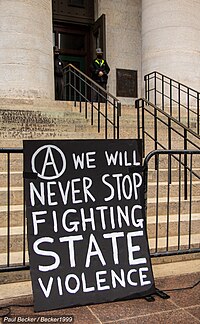

As such, states can resort to coercive means such as incarceration, expropriation, humiliation, and death threats to obtain the population's compliance with its rule and thus maintain order.

"[2] In other words, Weber describes the state as any organization that succeeds in holding the exclusive right to use, threaten, or authorize physical force against residents of its territory.

An expanded definition appears in Economy and Society: A compulsory political organization with continuous operations will be called a 'state' [if and] insofar as its administrative staff successfully upholds a claim to the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force (das Monopol legitimen physischen Zwanges) in the enforcement of its order.

[6] In regions where state presence is minimally felt, non-state actors can use their monopoly on violence to establish legitimacy, or maintain power.