Mont Cenis Pass Railway

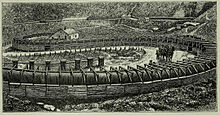

The Mont Cenis Pass Railway operated from 1868 to 1871 (with some interruptions) during the construction of the Fréjus Rail Tunnel through the Alps between Saint-Michel-de-Maurienne, southeast France and Susa, Piedmont, northwest Italy.

Although it would eventually be superseded by the tunnel, they believed that during its life, the cost of the pass railway would be repaid with a profit to them.

Until this railway was built, rail passengers had to cross the Alps by horse-drawn Stage coach in summer or sledge in winter.

[4] By the early 1860s most of a 1400-mile rail connection between Calais and Brindisi had been built, much of it by Thomas Brassey and John Barraclough Fell.

Work on the Fréjus or Mont Cenis tunnel had started in 1857 but it looked as though it would take many years to build, using traditional tools and gunpowder.

[3] A full rail service from Calais to Brindisi, continuing by sea to Alexandria, would take about 30 hours off the journey time from Britain to India, China and Australasia compared with the current option of Calais to Marseilles by rail and onwards by sea.

The increasing volumes of trade, in mail, passengers and goods presented a tempting prospect of profits to be made by crossing the Alpine barrier as well as an opportunity to strengthen the ties of Empire.

[12] In 1866, at a British Association meeting, Fell reported how four years earlier he had been asked to design some means of improving on the existing horse-drawn transport across the Alps over the Mont Cenis Pass.

They showed that the light locomotive would not work on the 1 in 12 slope without the central rail drive but could tow four wagons weighing 7 tons each with it.

[16] With this information, the Mont Cenis Concessionary Company was formed on 12 April 1864 to obtain concessions from the two governments to build a railway on the public road over the pass until the tunnel should be opened.

To provide additional evidence a second test line was constructed along the zig-zag section from Lanslebourg to the summit.

[20] The trials were observed by officials from the governments of France, Italy, Great Britain, Austria and Russia.

Where it was necessary for the track to cross the roadway on the level the tall centre rail was lowered into a trough by the operation of a lever.

At this late stage the most reputable French manufacturers were busy so they used Ernest Goüin et Cie. of Paris even though Alexander had reported on them unfavourably.

They found: 2,200 men employed, rails being laid at both ends and on the plateau of the line and a scarcity of horses owing to the Austro-Italian war.

On the French side the stones comprising the foundation of the road were so large that blasting was required to make holes for the fence.

When this dam finally burst, there was a deluge which caused damage at fifty places between Termignon and St Michel.

[31] In mid August the Board of Trade dispatched Captain Tyler to inspect the railway and the tunnel.

Tyler's official report on the tunnel was that 7,366 metres had been bored, 4,884 remained and that the French had passed through the hard quartz and returned to the softer schist.

On 12 September The Times published an offering of £125,000 of 7 per cent debentures, adding that the line would probably open in October.

A general meeting in November authorised an increase in the company's borrowing powers from £125,000 to £202,000 and an interest rate of 10 per cent.

[38] On 20 April, after a lot of work, a test train carrying 25 tons was taken from St Michel to Susa, returning the following day.

The party of 54 included Blount, Brogden, Buddicom, Fell, Cutbill, Bell, Blake, Alexander, Barnes, Gohierre, Desbrière, Crampton, Count Arrivabene and Signor Milla the Italian government commissioner.

[42] Travel by the train saved 6 hours over the stagecoach; the coaches were more spacious and comfortable and even the 1st class fare was 20 francs cheaper.

Then on the night of 17/18 August the Arc flooded again and washed away the Pont de la Denise, partly because of spoil left by tunnel builders for the standard railway.

[47] At a general meeting in February 1869 the operating accounts from 15 June to 31 October 1868 showed that the expenses were 73 per cent of receipts.

In the AGM on 10 February 1870 the board were unable to promise during 1870 to pay interest to bondholders or shareholders as traffic was still below expectations.

In September 1870, Fell reported to the British Association that: trains had travelled 200,000 miles and carried 100,000 passengers; the Indian Mail had never missed a connection and had taken 30 hours less than before; the journey time from Paris to Turin had been cut by one night.

Receipts were 11s 9½d[52] When Fell gave a paper to the British Association in 1870, the impressive progress of the tunnel led him to predict correctly that it would open before the end of 1871.

With these sharp curves, the rigidly fixed horizontal wheels did not follow readily irregularities in the centre rail.