Montana-class battleship

Five were approved for construction during World War II, but changes in wartime building priorities resulted in their cancellation in favor of continuing production of Essex-class aircraft carriers and Iowa-class battleships before any Montana-class keels were laid.

Consequently, the US Navy chose to cancel the Montana-class in favor of more urgently needed aircraft carriers as well as amphibious and anti-submarine vessels.

Because the Iowas were far enough along in construction and urgently needed to operate alongside the new Essex-class aircraft carriers, their orders were retained, making them completed the last US Navy battleships to be commissioned.

[1] After the ten-year construction moratorium that had been imposed by the Washington Treaty expired, the US Navy began building the North Carolina-class fast battleships in 1937 to replace old pre-World War I ships that were by then obsolescent.

On 31 March 1938, the US, Britain, and France exchanged notes indicating that they would accept increasing the displacement limit to 45,000 long tons (46,000 t).

The latter type, which eventually emerged essentially as an improved South Dakota, was capable of a speed of 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph), but work on the former proceeded at the same time.

The General Board intended it to become the next generation of standard-type battleships, which was to be set at 45,000-ton ships armed with twelve 16 in (406 mm) guns, and capable of 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph), the same speed as the South Dakotas.

The start of World War II in Europe, and particularly the Fall of France in June 1940 only increased the pressure to speed construction of new warships.

These were to have been built to the next battleship design, but the Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox, decided that these should be additional Iowa-class ships to speed up production.

They requested proposals from the Bureau of Construction and Repair (C&R) that conformed to the 45,000-ton limit, armed with twelve 16-inch guns, and capable of 27-knots.

[9] C&R initially responded with a design labeled "BB 65A", which used South Dakota as a baseline, but increased the length to accommodate the fourth main battery turret.

They realized that though the deck could be improved to provide a relatively narrow zone of immunity against plunging fire, strengthening the belt armor to protect against the heavier shell would increase displacement to as much as 55,000 long tons (56,000 t).

Several of these proposals experimented with mixed quadruple, triple, and double turrets for either ten or eleven guns to save weight but still increase firepower over the nine-gun South Dakotas.

[12] In October, the General Board asked for new twelve-gun designs that were sufficiently armored, which was estimated could be accomplished on a displacement of around 50,000 long tons (51,000 t).

During discussions in March, the decision was made to revert to externally applied belt armor, since the internal armor belts of the South Dakota and Iowa classes were more difficult to install and repair in the event of battle damage, and the weight savings associated with them no longer mattered now that displacement limits were gone.

The Board finally selected one of the designs, "BB 65-5A", which was armed with twelve guns on a displacement of 57,500 long tons (58,400 t), and capable of 28 knots.

These changes provided further savings in weight that allowed the bomb deck to be extended further aft, and improvements to the light anti-aircraft battery.

[16][17] The General Board planned to build four ships to the new design, which would have constituted a single battleship division, but five were authorized by the Two-Ocean Navy Act on 19 July 1940.

Work on the new locks for the Panama Canal was also halted in 1941, also owing to a shortage of steel due to the changing strategic and material priorities.

[20] In October 1942, work on the ships was again delayed by the order of some eighty destroyers, which were badly needed for the Battle of the Atlantic against German U-boats that were raiding the supply convoys to Britain.

[19] All five ships were ultimately cancelled on 21 July 1943, as production priorities had shifted decisively toward aircraft carriers, destroyers, and submarines.

[22] The time spent refining the Montana design was not entirely a waste, as the arrangement of the propulsion system was modified for the Midway-class aircraft carriers.

The Montanas' overall construction would have made extensive use of welding for joining structural plates and homogeneous armor, which saved weight compared to traditional riveting.

Like all of the US interwar designs, the Montanas would have had a flush main deck that was steeply flared at the bow to reduce the amount of water taken on in heavy seas.

[26] The Montanas were designed to carry 7,500 long tons (7,600 t) of fuel oil and had a nominal range of 15,000 nmi (27,800 km; 17,300 mi) at 15 kn (28 km/h; 17 mph).

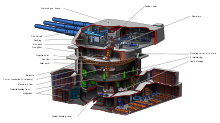

[28] While less powerful than the 212,000 hp (158,000 kW) powerplant used by the Iowas, the Montana's plant enabled the machinery spaces to be considerably more subdivided, with extensive longitudinal and traverse subdivisions of the boiler and engine rooms.

[30] The primary armament of a Montana-class battleship would have been twelve 16-inch (406 mm)/50 caliber Mark 7 guns, which were to be mounted in four three-gun turrets.

[31][32] The secondary armament for the Montana-class ships was to be twenty 5 in (127 mm)/54 cal Mark 16 dual-purpose guns housed in ten two-gun turrets along the superstructure.

Two of the compartments would be liquid loaded in order to disrupt the gas bubble of a torpedo warhead detonation while the bulkheads would elastically deform and absorb the energy.

The design of the Montana's torpedo defense system addressed a potential vulnerability of the South Dakota-type system, where caisson tests in 1939 showed that extending the main armor belt that tapers to the keel to act as one of the torpedo bulkheads had detrimental flooding effects due to the belt's rigidity.