Monty Hall problem

After the problem appeared in Parade, approximately 10,000 readers, including nearly 1,000 with PhDs, wrote to the magazine, most of them calling Savant wrong.

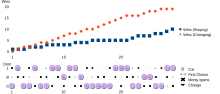

[5] Paul Erdős, one of the most prolific mathematicians in history, remained unconvinced until he was shown a computer simulation demonstrating Savant's predicted result.

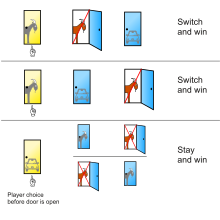

[1] The solution presented by Savant in Parade shows the three possible arrangements of one car and two goats behind three doors and the result of staying or switching after initially picking door 1 in each case:[11] A player who stays with the initial choice wins in only one out of three of these equally likely possibilities, while a player who switches wins in two out of three.

Stibel et al. proposed that working memory demand is taxed during the Monty Hall problem and that this forces people to "collapse" their choices into two equally probable options.

They report that when the number of options is increased to more than 7 people tend to switch more often; however, most contestants still incorrectly judge the probability of success to be 50%.

[19] Numerous examples of letters from readers of Savant's columns are presented and discussed in The Monty Hall Dilemma: A Cognitive Illusion Par Excellence.

When first presented with the Monty Hall problem, an overwhelming majority of people assume that each door has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter.

[23] Most statements of the problem, notably the one in Parade, do not match the rules of the actual game show[10] and do not fully specify the host's behavior or that the car's location is randomly selected.

[25] Although these issues are mathematically significant, even when controlling for these factors, nearly all people still think each of the two unopened doors has an equal probability and conclude that switching does not matter.

[26] People strongly tend to think probability is evenly distributed across as many unknowns as are present, whether or not that is true in the particular situation under consideration.

The typical behavior of the majority, i.e., not switching, may be explained by phenomena known in the psychological literature as: Experimental evidence confirms that these are plausible explanations that do not depend on probability intuition.

[31][32] Another possibility is that people's intuition simply does not deal with the textbook version of the problem, but with a real game show setting.

A show master playing deceitfully half of the times modifies the winning chances in case one is offered to switch to "equal probability".

[38] In Morgan et al.,[38] four university professors published an article in The American Statistician claiming that Savant gave the correct advice but the wrong argument.

Later in their response to Hogbin and Nijdam,[45] they did agree that it was natural to suppose that the host chooses a door to open completely at random when he does have a choice, and hence that the conditional probability of winning by switching (i.e., conditional given the situation the player is in when he has to make his choice) has the same value, 2/3, as the unconditional probability of winning by switching (i.e., averaged over all possible situations).

[46] One discussant (William Bell) considered it a matter of taste whether one explicitly mentions that (by the standard conditions) which door is opened by the host is independent of whether one should want to switch.

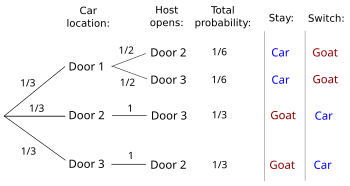

The simple solutions above show that a player with a strategy of switching wins the car with overall probability 2/3, i.e., without taking account of which door was opened by the host.

According to Bayes' rule, the posterior odds on the location of the car, given that the host opens door 3, are equal to the prior odds multiplied by the Bayes factor or likelihood, which is, by definition, the probability of the new piece of information (host opens door 3) under each of the hypotheses considered (location of the car).

[44] A simple way to demonstrate that a switching strategy really does win two out of three times with the standard assumptions is to simulate the game with playing cards.

The confusion as to which formalization is authoritative has led to considerable acrimony, particularly because this variant makes proofs more involved without altering the optimality of the always-switch strategy for the player.

However, Savant made it clear in her second follow-up column that the intended host's behavior could only be what led to the 2/3 probability she gave as her original answer.

Determining the player's best strategy within a given set of other rules the host must follow is the type of problem studied in game theory.

In reverse with respect to the typical Monty hall problem Laplace discusses the probability of drawing two white balls.

One of the prisoners begs the warden to tell him the name of one of the others to be executed, arguing that this reveals no information about his own fate but increases his chances of being pardoned from 1/3 to 1/2.

As Monty Hall wrote to Selvin: And if you ever get on my show, the rules hold fast for you – no trading boxes after the selection.A version of the problem very similar to the one that appeared three years later in Parade was published in 1987 in the Puzzles section of The Journal of Economic Perspectives.

[3] Though Savant gave the correct answer that switching would win two-thirds of the time, she estimates the magazine received 10,000 letters including close to 1,000 signed by PhDs, many on letterheads of mathematics and science departments, declaring that her solution was wrong.

In November 1990, an equally contentious discussion of Savant's article took place in Cecil Adams's column "The Straight Dope".

The Parade column and its response received considerable attention in the press, including a front-page story in The New York Times in which Monty Hall himself was interviewed.

[4] Hall understood the problem, giving the reporter a demonstration with car keys and explaining how actual game play on Let's Make a Deal differed from the rules of the puzzle.

In the article, Hall pointed out that because he had control over the way the game progressed, playing on the psychology of the contestant, the theoretical solution did not apply to the show's actual gameplay.