Morlachs

Then, when the community straddled the Venetian–Ottoman border until the 17th century, it referred only to the Slavic-speaking people of the Dalmatian Hinterland, Orthodox and Catholic, on both the Venetian and Turkish side.

[1] The exonym ceased to be used in an ethnic sense by the end of the 18th century, and came to be viewed as derogatory, but has been renewed as a social or cultural anthropological subject.

[6][7] Petar Skok suggested that while the Latin maurus is derived from the Greek μαύρος ("dark"), the diphthongs au > av indicates a specific Dalmato-Romanian lexical remnant.

[9] The first reference to this theory comes from the 18th-century priest Alberto Fortis, who wrote extensively about the Morlachs in his book Viaggio in Dalmazia ("Journey to Dalmatia", 1774).

[13] According to Dana Caciur, the Morlach community from the Venetian view, as long as they share a specific lifestyle, could represent a mixture of Vlachs, Croats, Serbs, Bosnians and other people.

Although they were often seen by urban dwellers as strangers and "those people" from the periphery,[15] in 1730 provveditore Zorzi Grimani described them as "ferocious, but not indomitable" by nature, Edward Gibbon called them "barbarians",[16][17] and Fortis praised their "noble savagery", moral, family, and friendship virtues, but also complained about their persistence in keeping to old traditions.

He found that they sang melancholic verses of epic poetry related to the Ottoman occupation,[18] accompanied with the traditional single stringed instrument called gusle.

[24] Lovrić made no distinction between the Vlachs/Morlachs and the Dalmatians and Montenegrins, whom he considered Slavs, and was not at all bothered by the fact that the Morlachs were predominantly Orthodox Christian.

[31] On Krk island, where a community was settled from the 15th century, two small samples of the language were recorded in 1819 by the local priest from Bajčić in the forms of Lord's Prayer and Hail Mary, as shown below:[32] “Cače nostru, kirle jesti in čer Neka se sveta nomelu tev Neka venire kraljestvo to Neka fiè volja ta, kasi jaste in čer, asa si prepemint Pire nostre desa kazi da ne astec Si lasne delgule nostre, kasisi noj lesam al delsnic a nostri Si nun lesaj in ne napasta Nego ne osloboda de rev.

[40] Authorities of Šibenik in 1450 gave permission to enter the city to Morlachs and some Vlachs who called themselves Croats who were in the same economic and social position at that time.

[41] According to scholar Fine, the early Vlachs probably lived on Croatian territory even before the 14th century, being the progeny of romanized Illyrians and pre-Slavic Romance-speaking people.

[42] During the 14th century, Vlach settlements existed throughout much of today's Croatia, from the northern island Krk, around the Velebit and Dinara mountains, and along the southern rivers Krka and Cetina.

[54] The Istro-Romanians, and other Vlachs (or Morlachs), had settled Istria (and mountain Ćićarija) after the various devastating outbreaks of the plague and wars between 1400 and 1600,[55] reaching the island of Krk.

During the Ottoman–Venetian war of 1499-1502, a considerable demographic shift took place in the Dalmatian hinterland, leading to the abandonment of many of the region settlements by their previous inhabitants.

[60] Referred to as Morlachs in the Venetian records, the newcomers to Šibenik hinterland (Serbo-Croatian: Zagora) came from Herzegovina and among them, three Vlach clans (katuns) predominated: the Mirilovići, the Radohnići, and the Vojihnići.

[65] From the 16th century onwards, the name "Morlach" became specifically used by the Venetians to refer the any inhabitant of the hinterland, as opposed to those of the coastal towns, in an area stretching from the north of Kotor to the Kvarner Gulf region.

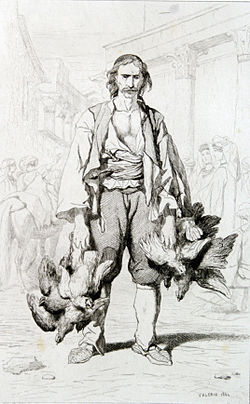

In particular, Morlachs from the hinterland played an important role in trade, bringing corn, meat, cheese and wool to towns like Šibenik, and buying fabrics, jewelry, clothing, delicacies and, above all, salt.

[69] In 1593, provveditore generale (Overseer) Cristoforo Valier mentioned three nations constituting the Uskoks: the "natives of Senj, Croatians, and Morlachs from the Turkish parts".

[78][79] In 1793, at the carnival in Venice, a play about Morlachs, Gli Antichi Slavi ("antique Slavs"), was performed, and in 1802 it was reconceived as a ballet Le Nozze dei Morlacchi.

[17] Thomas Graham Jackson described Morlach women as half-savages wearing "embroidered leggings thet give them the appearance of Indian squaws".