Morrill Tariff

It was the twelfth of the seventeen planks in the platform of the incoming Republican Party, which had not yet been inaugurated, and the tariff appealed to industrialists and factory workers as a way to foster rapid industrial growth.

[3] Two additional tariffs sponsored by Morrill, each higher than the previous one, were passed under President Abraham Lincoln to raise revenue that was urgently needed during the American Civil War.

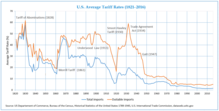

Tariff in United States history has often been made high to encourage the development of domestic industry, and had been advocated, especially by the Whig Party and its longtime leader, Henry Clay.

Some former Whigs from the border states and the Upper South remained in Congress as "Opposition," "Unionist," or "American," (Know Nothing) members and supported higher tariffs.

Ways and Means members Morrill and Henry Winter Davis, a Maryland "American," produced the Republican proposal to raise the tariffs.

[citation needed] Supporters of the specific rates argued that they were necessary because European exporters routinely provided US customers with fake invoices showing lower prices for goods than were actually paid.

On February 14, 1861, President-elect Lincoln told an audience in Pittsburgh that he would make a new tariff his priority in the next session if the bill did not pass by his inauguration, on March 4.

A recent historian concludes that "the impetus for revising the tariff arose as an attempt to augment revenue, stave off 'ruin,' and address the accumulating debt.

[10] There were some minor amendments related to the tariffs on tea and coffee, which required a conference committee with the House, but they were resolved, and the final bill was approved by unanimous consent on March 2.

Therefore, Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, despite being a longtime free-trader, worked with Morrill to pass a second tariff bill in summer 1861, which raised rates another 10% to generate more revenue.

"[17] When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, British public opinion was sympathetic to the Confederacy, in part because of lingering agitation over the tariff.

It greatly lessened the profits of the American markets to English manufacturers and merchants, to a degree which caused serious mercantile distress in that country.

Moreover, the British nation was then in the first flush of enthusiasm over free trade, and, under the lead of extremists like Cobden and Gladstone, was inclined to regard a protective tariff as essentially and intrinsically immoral, scarcely less so than larceny or murder.

On December 28, 1861, Dickens published a lengthy article, believed to be written by Henry Morley,[19] which blamed the American Civil War on the Morrill Tariff: If it be not slavery, where lies the partition of the interests that has led at last to actual separation of the Southern from the Northern States?...

The love of money is the root of this, as of many other evils.... [T]he quarrel between the North and South is, as it stands, solely a fiscal quarrel.Others, such as John Stuart Mill, denied tariffs had anything to do with the conflict: ...what are the Southern chiefs fighting about?

Many years ago, when General Jackson was President, South Carolina did nearly rebel (she never was near separating) about a tariff; but no other State abetted her, and a strong adverse demonstration from Virginia brought the matter to a close.

Marx wrote extensively in the British press and served as a London correspondent for several North American newspapers including Horace Greeley's New York Tribune.

In October 1861, he wrote: Naturally, in America everyone knew that from 1846 to 1861 a free trade system prevailed, and that Representative Morrill carried his protectionist tariff through Congress only in 1861, after the rebellion had already broken out.

[22] According to the historian Heather Cox Richardson, Morrill intended to offer protection to both the usual manufacturing recipients and a broad group of agricultural interests.

The duty on sugar might well be expected to appease Southerners opposed to tariffs, and, notably, wool and flaxseed production were growing industries in the West.

"In adjusting the details of a tariff," Morrill explained with a rhetorical flourish in his introduction of the bill, "I would treat agriculture, manufactures, mining, and commerce, as I would our whole people—as members of one family, all entitled to equal favor, and no one to be made the beast of burden to carry the packs of others.

However, he also gives reason to suspect that the bill's motives were intended to put high rates of protection on iron and wool to attract the West and Pennsylvania: The important change which they (the sponsors) proposed to make from the provisions of the tariff of 1846 was to substitute specific for ad-valorem duties.

The most important direct changes made by the act of 1861 were in the increased duties on iron and on wool, by which it was hoped to attach to the Republican party Pennsylvania and some of the Western States"[24]Henry C. Carey, who assisted Morrill in drafting the bill and was one of its most vocal supporters, strongly emphasized its importance to the Republican Party in his January 2, 1861 letter to Lincoln: "the success of your administration is wholly dependent upon the passage of the Morrill bill at the present session."

According to Carey: With it, the people will be relieved — your term will commence with a rising wave of prosperity — the Treasury will be filled and the party that elected you will be increased and strengthened.

There is but one way to make the Party a permanent one, & that is, by the prompt repudiation to the free trade system.Representative John Sherman later wrote: The Morrill tariff bill came nearer than any other to meeting the double requirement of providing ample revenue for the support of the government and of rendering the proper protection to home industries.

[25]While slavery dominated the secession debate in the south,[26] the Morrill tariff provided an issue for secessionist agitation in some southern states.

The people of the South have been taxed by duties on imports, not for revenue, but for an object inconsistent with revenue— to promote, by prohibitions, Northern interests in the productions of their mines and manufactures.

[31] Historians, James Huston notes, have been baffled by the role of high tariffs in general and have offered multiple conflicting interpretations over the years.

Beard argued in the 1920s that very long-term economic issues were critical, with the pro-tariff industrial Northeast forming a coalition with the anti-tariff agrarian Midwest against the plantation South.

According to Luthin in the 1940s, "Historians are not unanimous as to the relative importance which Southern fear and hatred of a high tariff had in causing the secession of the slave states.