Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology

[3] Nikolay Kudryavtsev (Кудрявцев Николай Николаевич]), the president of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology has signed a letter of support for the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

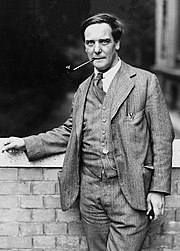

[5] In a letter to Stalin in February 1946, Kapitsa argued for the need for such a school, which he tentatively called the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, to better maintain and develop the country's defense potential.

On March 10, 1946, the government issued a decree mandating the establishment of a "College of Physics and Technology" (Russian: Высшая физико-техническая школа).

The exact circumstances are not documented, but the common assumption is that Kapitsa's refusal to participate in the Soviet atomic bomb project and his disfavor with the government and communist party that followed, cast a shadow over an independent school based largely on his ideas.

Instead, a new government decree was issued on November 25, 1946, establishing the new school as a Department of Physics and Technology within Moscow State University.

It was headed by the MSU "vice rector for special issues"—a position created specifically to shield the department from the university management.

[8] As Kapitsa expected, the special status of the new school with its different "rules of engagement" caused much consternation and resistance within the university.

The immediate cult status that Phystech gained among talented young people, drawn by the challenge and romanticism of working on the forefront of science and technology and on projects of "government importance," many of them classified, made it an untouchable rival of every other school in the country, including MSU's own Department of Physics.

At the same time, the increasing disfavor of Kapitsa with the government (in 1950 he was essentially under house arrest) and anti-semitic repressions of the late 1940s made Phystech an easy target of intrigues and accusations of "elitism" and "rootless cosmopolitanism."

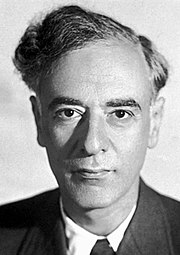

[10] Apart from Kapitsa, other prominent scientists who taught at MIPT in the years that followed included Nobel prize winners Nikolay Semyonov, Lev Landau, Alexandr Prokhorov, Vitaly Ginzburg; and Academy of Sciences members Sergey Khristianovich, Mikhail Lavrentiev, Mstislav Keldysh, Sergey Korolyov and Boris Rauschenbach.

Traditionally, applicants were required to take written and oral exams in both mathematics and physics, write an essay and have an interview with the faculty.

The strongest performers in national physics and mathematics competitions and IMO/IPhO participants are granted admission without exams, subject only to the interview.

Most subjects include a combination of lectures and seminars (problem-solving study sessions in smaller groups) or laboratory experiments.

Andre Geim, a graduate and Nobel prize winner stated "The pressure to work and to study was so intense that it was not a rare thing for people to break and leave and some of them ended up with everything from schizophrenia to depression to suicide.

The following list of institutes is currently far from being complete: In addition, a number of Russian and Western companies act as base organizations of MIPT.