Great Mosque of Kairouan

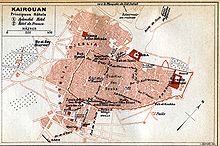

[1] Established by the Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi in the year 50 AH (670AD/CE) at the founding of the city of Kairouan, the mosque occupies an area of over 9,000 square metres (97,000 sq ft).

In 1967, major restoration works, executed during five years and conducted under the direction of the National Institute of Archeology and Art, were achieved throughout the monument, and were ended with an official reopening of the mosque during the celebration of the Mawlid of 1972.

On additions and embellishments made to the building by the Aghlabid emir Abu Ibrahim, Ibn Nagi gives the following account: « He built in the mosque of Kairouan the cupola that rises over the entrance to the central nave, together with the two colonnades which flank it from both sides, and the galleries were paved by him.

»[31] At the same time, the doctor and Anglican priest Thomas Shaw (1692–1751),[32] touring the Tunis Regency and passes through Kairouan in 1727, described the mosque as that: "which is considered the most beautiful and the most sacred of Berberian territories", evoking for example: "an almost unbelievable number of granite columns".

At the end of the nineteenth century, the French writer Guy de Maupassant expresses in his book La vie errante (The Wandering Life), his fascination with the majestic architecture of the Great Mosque of Kairouan as well as the effect created by countless columns: "The unique harmony of this temple consists in the proportion and the number of these slender shafts upholding the building, filling, peopling, and making it what it is, create its grace and greatness.

[12][36] However, Arab geographers and historians of the Middle Ages Al-Muqaddasi and Al-Bakri reported the existence, around the tenth and eleventh centuries, of about ten gates named differently from today.

[12] The monumental entrance, work of the Hafsid sovereign Abu Hafs `Umar ibn Yahya (reign from 1284 to 1295),[37] is entered in a salient square, flanked by ancient columns supporting horseshoe arches and covered by a dome on squinches.

[12] The front façade of the porch has a large horseshoe arch relied on two marble columns and surmounted by a frieze adorned with a blind arcade, all crowned by serrated merlons (in a sawtooth arrangement).

The portico on the south side of the courtyard, near the prayer hall, includes in its middle a large dressed stone pointed horseshoe arch which rests on ancient columns of white veined marble with Corinthian capitals.

Near its centre is an horizontal sundial, bearing an inscription in naskhi engraved on the marble dating from 1258 AH (which corresponds to the year 1843) and which is accessed by a little staircase; it determines the time of prayers.

[62] Enlightened by chandeliers which are applied in countless small glass lamps,[63] the nave opens into the south portico of the courtyard by a monumental delicately carved wooden door, made in 1828 under the reign of the Husainids.

According to the German archaeologist Christian Ewert, the special arrangement of reused columns and capitals surrounding the mihrab obeys to a well-defined program and would draw symbolically the plan of the Dome of the Rock.

[58] The wooden rods, which usually sink to the base of the transom, connect the columns together and maintain the spacing of the arches, thus enhancing the stability of all structures which support the ceiling of the prayer hall.

The latter, which its hemispherical cap is cut by 24 concave grooves radiating around the top,[73] is based on ridged horns shaped shell and a drum pierced by eight circular windows which are inserted between sixteen niches grouped by two.

[56][74] The niches are covered with carved stone panels, finely adorned with characteristic geometric, vegetal and floral patterns of the Aghlabid decorative repertoire: shells, cusped arches, rosettes, vine-leaf, etc.

Wooden brackets offer a wide variety of style and decor in the shape of a crow or a grasshopper with wings or fixed, they are characterised by a setting that combines floral painted or carved, with grooves.

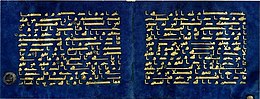

The oldest boards date back to the Aghlabid period (ninth century) and are decorated with scrolls and rosettes on a red background consists of squares with concave sides in which are inscribed four-petaled flowers in green and blue, and those performed by the Zirid dynasty (eleventh century) are characterised by inscriptions in black kufic writing with gold rim and the uprights of the letters end with lobed florets, all on a brown background adorned with simple floral patterns.

Divided into two groups, they are dated from the beginning of the second half of the ninth century but it is not determined with certainty whether they were made in Baghdad or in Kairouan by a Baghdadi artisan, the controversy over the origin of this precious collection agitates the specialists.

The horseshoe arch of the mihrab, stilted and broken at the top, rest on two columns of red marble with yellow veins, which surmounted with Byzantine style capitals that carry two crossbeams carved with floral patterns, each one is decorated with a Kufic inscription in relief.

The wall of the mihrab is covered with 28 panels of white marble, carved and pierced, which have a wide variety of plant and geometric patterns including the stylised grape leaf, the flower and the shell.

Covered with a thick coating completely painted, the concavity of the arch is decorated with intertwined scrolls enveloping stylised five-lobed vine leaves, three-lobed florets and sharp clusters, all in yellow on midnight blue background.

[80] Probably made by cabinetmakers of Kairouan (some researchers also refer to Baghdad), it consists of an assembly of more than 300 finely carved wood pieces with an exceptional ornamental wealth (vegetal and geometric patterns refer to the Umayyad and Abbasid models), among which about 90 rectangular panels carved with plenty of pine cones, grape leaves, thin and flexible stems, lanceolate fruits and various geometric shapes (squares, diamonds, stars, etc.).

The upper edge of the minbar ramp is adorned with a rich and graceful vegetal decoration composed of alternately arranged foliated scrolls, each one containing a spread vine-leaf and a cluster of grapes.

Although it has existed for more than eleven centuries, all panels, with the exception of nine, are originals and are in a good state of conservation, the fineness of the execution of the minbar makes it a great masterpiece of Islamic wood carving referring to Paul Sebag.

The maqsura, located near the minbar, consists of a fence bounding a private enclosure that allows the sovereign and his senior officials to follow the solemn prayer of Friday without mingling with the faithful.

Jewel of the art of woodwork produced during the reign of the Zirid prince Al-Mu'izz ibn Badis and dated from the first half of the eleventh century, it is considered the oldest still in place in the Islamic world.

[82] Its main adornment is a frieze that crowns calligraphy, the latter surmounted by a line of pointed openwork merlons, features an inscription in flowery kufic character carved on the background of interlacing plants.

Other works of art such as the crowns of light (circular chandeliers) made in cast bronze, dating from the Fatimid-Zirid period (around the tenth to the early eleventh century), originally belonged to the furniture of the mosque.

These polycandelons, now scattered in various Tunisian museums including Raqqada, consist of three chains supporting a perforated brass plate, which has a central circular ring around which radiate 18 equidistant poles connected by many horseshoe arches and equipped for each of two landmarks flared.

[86] In addition to studies on the deepening of religious thought and Maliki jurisprudence, the mosque also hosted various courses in secular subjects such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine and botany.