Mosquito net

[2] To be effective, the mesh of a mosquito net must be fine enough to exclude such insects without obscuring visibility or ventilation to unacceptable levels.

Netting with 285 holes per square inch is ideal because it is very breathable but will prevent even the smallest mosquito from entering.

Though use of the term dates from the mid-18th century,[1] Indian literature from the late medieval period has references to the usage of mosquito nets in ritual Hindu worship.

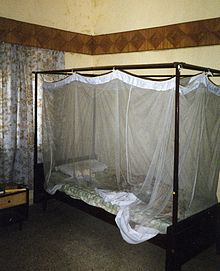

The frame is usually self-supporting or freestanding although it can be designed to be attached from the top to an alternative support such as tree limbs.

[15] Mosquito netting can be hung over beds from the ceiling or a frame, built into tents, or installed in windows and doors.

ITNs have been shown to be the most cost-effective prevention method against malaria and are part of WHO's Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

However, mathematical modeling has suggested that disease transmission may be exacerbated after bed nets have lost their insecticidal properties under certain circumstances.

[27] In December 2019 it was reported that West African populations of Anopheles gambiae include mutants with higher levels of sensory appendage protein 2 (a type of chemosensory protein in the legs), which binds to pyrethroids, sequestering them and so preventing them from functioning, thus making the mosquitoes with this mutation more likely to survive contact with bednets.

[28] While some experts argue that international organizations should distribute ITNs and LLINs to people for free to maximize coverage (since such a policy would reduce price barriers), others insist that cost-sharing between the international organization and recipients would lead to greater use of the net (arguing that people will value a good more if they pay for it).

Additionally, proponents of cost-sharing argue that such a policy ensures that nets are efficiently allocated to the people who most need them (or are most vulnerable to infection).

However, a randomized controlled trial study of ITNs uptake among pregnant women in Kenya, conducted by economists Pascaline Dupas and Jessica Cohen, found that cost-sharing does not necessarily increase the usage intensity of ITNs nor does it induce uptake by those most vulnerable to infection, as compared to a policy of free distribution.

Dupas and Cohen's findings support the argument that free distribution of ITNs can be more effective than cost-sharing in increasing coverage and saving lives.

"[29] The researchers base their conclusions about the cost-effectiveness of free distribution on the proven spillover benefits of increased ITN usage.

Standard ITNs must be replaced or re-treated with insecticide after six washes and, therefore, are not seen as a convenient, effective long-term solution to the malaria problem.

[42] The conclusion of this study showed that as the number of houses which used insecticide treated bed nets increased the population density of female anopheles gambiae decreased.

A 2019 study in PLoS ONE found that a campaign to distribute mosquito bednets in the Democratic Republic of Congo led to a 41% decline mortality for children under five who lived in areas with a high malaria risk.

A decrease in per capita income exaggerates a high demand for resources such as water and food resulting in civil unrest among communities.

Mosquito nets have been observed to be used in fisheries across the world, where their strength, light weight and free or cheap accessibility make them an attractive tool for fishing.