Ibn Arabi

[3][4] After his death, practitioners of Sufism began referring to him by the honorific title Shaykh al-Akbar, (Arabic: الشيخ الأكبر)[5] from which the name Akbarism is derived.

[12] In his Futūḥāt al-Makkīyah, he writes of a deceased maternal uncle, a prince of Tlemcen who abandoned wealth for an ascetic life after encountering a Sufi mystic.

[13] His paternal ancestry came from Yemen and belongs to one of the oldest Arab strains in Andalusia, they having probably migrated during the second waves of the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula.

"[16] When Ibn ʿArabī stayed in Anatolia for several years, according to various Arabic and Persian sources, he married the widow of Majduuddin and took charge of the education of his young son, Sadruddin al-Qunawi.

[18] Ibn 'Arabi studied under many scholars of his time, many of whom were mentioned in the ijaza (permission to teach and transmit) written to al-Muzaffar Baha' al-Din Ghazi[Note 1] (son of al-'Adil I the Ayyubid).

Ibn Arabi said that from this first meeting, he had learned to perceive a distinction between formal knowledge of rational thought and the unveiling of insights into the nature of things.

He then visited various places in the Maghreb,[39] including Fez in Morocco, where he accepted spiritual mentorship under Mohammed ibn Qasim al-Tamimi.

[44] In 1200, he took leave from one of his most important teachers, Shaykh Abu Ya'qub Yusuf ibn Yakhlaf al-Kumi, then living in the town of Salé.

[39] He lived in Mecca for three years, and there began writing his work Futūḥāt al-Makkiyya (الفتوحات المكية), The Meccan Illuminations—only part of which has been translated into English by various scholars such as Eric Winkel.

[47] There he spent the month of Ramaḍan and composed Tanazzulāt al-Mawṣiliyya (تنزلات الموصلية), Kitāb al-Jalāl wa’l-Jamāl (كتاب الجلال والجمال, "The Book of Majesty and Beauty") and Kunh mā lā Budda lil-MurīdMinhu.

Later in 1207, he returned to Mecca where he continued to study and write, spending his time with his friend Abū Shujā bin Rustem and family, including Niẓām.

[56][57] Many prominent Ibn Arabi scholars, including Addas, Chodkiewicz, Gril, Winkel and Al-Gorab, contend that he did not follow any madhhab.

One of my shaykhs, whom I questioned, informed me that this man is an authority in the field of science of Hadeeth.”Goldziher says, "The period between the sixth (hijri) and the seventh century seems also to have been the prime of the Ẓāhirite school in Andalusia.

[68] Arabi may have first coined this term in referring to Adam as found in his work Fusus al-hikam, explained as an individual who binds himself with the Divine and creation.

[69] Taking an idea already common within Sufi culture, Ibn Arabi applied deep analysis and reflection on the concept of a perfect human and one's pursuit in fulfilling this goal.

[70] In this philosophical metaphor, Ibn Arabi compares an object being reflected in countless mirrors to the relationship between God and his creatures.

Ibn Arabi expressed that through self manifestation one acquires divine knowledge, which he called the primordial spirit of Muhammad and all its perfection.

[72] Ibn Arabi regarded the first entity brought into existence as the reality or essence of Muhammad (al-ḥaqīqa al-Muhammadiyya), master of all creatures, and a primary role model for human beings to emulate.

[73] Ibn Arabi also described Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and all other prophets and various Anbiya' Allah (Muslim messengers) as perfect men, but never tires of attributing lordship, inspirational source, and highest rank to Muhammad.

[75] As such, the figure of Ibn 'Abd al-Salam was claimed by each faction of the Ibn-'Arabi controversy due to his impeccable record as a staunch champion of the shari'a.

Suddenly, the servant recalled that Ibn 'Abd al-Salam had promised to reveal to him the identity of the supreme saint of the epoch, the "Pole of the Age".

[83] In al-Fayruzabadi's version of the story, Ibn 'Abd al-Salam is presented as a secret admirer of his who was fully aware of the latter's exalted status in the Sufi hierarchy.

However, as a public figure, Ibn 'Abd al-Salam was careful to conceal his genuine opinion of the controversial Sufi to "preserve the outward aspect of the religious law".

A bitter critic of Ibn 'Arabi's monistic views, al-Fasi rejected the Sufi version of the story as sheer fabrication.

Yet, as a scrupulous muhaddith, he tried to justify his position through the methods current in hadith criticism:[85] "I have a strong suspicion that this story was invented by the extremist Sufis who were infatuated with Ibn 'Arabi.

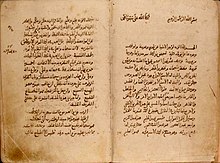

Recent research suggests that over 100 of his works have survived in manuscript form, although most printed versions have not yet been critically edited and include many errors.

There have been many commentaries on Ibn 'Arabī's Fuṣūṣ al-Ḥikam: Osman Yahya named more than 100 while Michel Chodkiewicz precises that "this list is far from exhaustive.

A recent English translation of Ibn 'Arabī's own summary of the Fuṣūṣ, Naqsh al-Fuṣūṣ (The Imprint or Pattern of the Fusus) as well a commentary on this work by 'Abd al-Raḥmān Jāmī, Naqd al-Nuṣūṣ fī Sharḥ Naqsh al-Fuṣūṣ (1459), by William Chittick was published in Volume 1 of the Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi Society (1982).

In Urdu, the most widespread and authentic translation was made by Shams Ul Mufasireen Bahr-ul-uloom Hazrat (Muhammad Abdul Qadeer Siddiqi Qadri -Hasrat), the former Dean and Professor of Theology of the Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Maulvi Abdul Qadeer Siddiqui has made an interpretive translation and explained the terms and grammar while clarifying the Shaikh's opinions.