Multiverse

[1][a] Together, these universes are presumed to comprise everything that exists: the entirety of space, time, matter, energy, information, and the physical laws and constants that describe them.

One common assumption is that the multiverse is a "patchwork quilt of separate universes all bound by the same laws of physics.

Critics argue that the multiverse concept lacks testability and falsifiability, which are essential for scientific inquiry, and that it raises unresolved metaphysical issues.

Max Tegmark and Brian Greene have proposed different classification schemes for multiverses and universes.

Brian Greene's nine types of multiverses include quilted, inflationary, brane, cyclic, landscape, quantum, holographic, simulated, and ultimate.

The ideas explore various dimensions of space, physical laws, and mathematical structures to explain the existence and interactions of multiple universes.

Some other multiverse concepts include twin-world models, cyclic theories, M-theory, and black-hole cosmology.

According to some, the idea of infinite worlds was first suggested by the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Anaximander in the sixth century BCE.

[citation needed] The American philosopher and psychologist William James used the term "multiverse" in 1895, but in a different context.

[24] Dr. Ranga-Ram Chary, after analyzing the cosmic radiation spectrum, found a signal 4,500 times brighter than it should have been, based on the number of protons and electrons scientists believe existed in the very early universe.

This signal—an emission line that arose from the formation of atoms during the era of recombination—is more consistent with a universe whose ratio of matter particles to photons is about 65 times greater than our own.

If additional protons and electrons had been added to our universe during recombination, more atoms would have formed, more photons would have been emitted during their formation, and the signature line that arose from all of these emissions would be greatly enhanced.

[24] Chary also noted:[25]Unusual claims like evidence for alternate universes require a very high burden of proof.

[25] Modern proponents of one or more of the multiverse hypotheses include Lee Smolin,[26] Don Page,[27] Brian Greene,[28][29] Max Tegmark,[30] Alan Guth,[31] Andrei Linde,[32] Michio Kaku,[33] David Deutsch,[34] Leonard Susskind,[35] Alexander Vilenkin,[36] Yasunori Nomura,[37] Raj Pathria,[38] Laura Mersini-Houghton,[39] Neil deGrasse Tyson,[40] Sean Carroll[41] and Stephen Hawking.

[42] Scientists who are generally skeptical of the concept of a multiverse or popular multiverse hypotheses include Sabine Hossenfelder,[43] David Gross,[44] Paul Steinhardt,[45][46] Anna Ijjas,[46] Abraham Loeb,[46] David Spergel,[47] Neil Turok,[48] Viatcheslav Mukhanov,[49] Michael S. Turner,[50] Roger Penrose,[51] George Ellis,[52][53] Joe Silk,[54] Carlo Rovelli,[55] Adam Frank,[56] Marcelo Gleiser,[56] Jim Baggott[57] and Paul Davies.

Ellis also explained that some theorists do not believe the lack of empirical testability and falsifiability is a major concern, but he is opposed to that line of thinking: Many physicists who talk about the multiverse, especially advocates of the string landscape, do not care much about parallel universes per se.

Their theories live or die based on internal consistency and, one hopes, eventual laboratory testing.

He points out that it ultimately leaves those questions unresolved because it is a metaphysical issue that cannot be resolved by empirical science.

But we should name it for what it is.Philosopher Philip Goff argues that the inference of a multiverse to explain the apparent fine-tuning of the universe is an example of Inverse Gambler's Fallacy.

In May 2020, astrophysicist Ethan Siegel expressed criticism in a Forbes blog post that parallel universes would have to remain a science fiction dream for the time being, based on the scientific evidence available to us.

[63] Scientific American contributor John Horgan also argues against the idea of a multiverse, claiming that they are "bad for science.

"[64] Max Tegmark and Brian Greene have devised classification schemes for the various theoretical types of multiverses and universes that they might comprise.

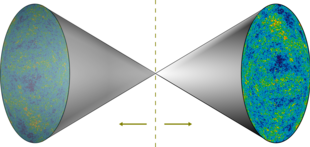

In the eternal inflation theory, which is a variant of the cosmic inflation theory, the multiverse or space as a whole is stretching and will continue doing so forever,[68] but some regions of space stop stretching and form distinct bubbles (like gas pockets in a loaf of rising bread).

[67] According to Yasunori Nomura,[37] Raphael Bousso, and Leonard Susskind,[35] this is because global spacetime appearing in the (eternally) inflating multiverse is a redundant concept.

For instance, a TOE involving a set of different types of entities (denoted by words, say) and relations between them (denoted by additional words) is nothing but what mathematicians call a set-theoretical model, and one can generally find a formal system that it is a model of.He argues that this "implies that any conceivable parallel universe theory can be described at Level IV" and "subsumes all other ensembles, therefore brings closure to the hierarchy of multiverses, and there cannot be, say, a Level V."[30] Jürgen Schmidhuber, however, says that the set of mathematical structures is not even well-defined and that it admits only universe representations describable by constructive mathematics—that is, computer programs.

[74] The American theoretical physicist and string theorist Brian Greene discussed nine types of multiverses:[75] There are models of two related universes that e.g. attempt to explain the baryon asymmetry – why there was more matter than antimatter at the beginning – with a mirror anti-universe.

If there were a large (possibly infinite) number of universes, each with possibly different physical laws (or different fundamental physical constants), then some of these universes (even if very few) would have the combination of laws and fundamental parameters that are suitable for the development of matter, astronomical structures, elemental diversity, stars, and planets that can exist long enough for life to emerge and evolve.

An early form of this reasoning is evident in Arthur Schopenhauer's 1844 work "Von der Nichtigkeit und dem Leiden des Lebens", where he argues that our world must be the worst of all possible worlds, because if it were significantly worse in any respect it could not continue to exist.

[91] However, proponents argue that in terms of Kolmogorov complexity the proposed multiverse is simpler than a single idiosyncratic universe.

[citation needed] It has been suggested that a universe that "contains life, in the form it has on Earth, is in a certain sense radically non-ergodic, in that the vast majority of possible organisms will never be realized".