Murder of the Romanov family

The Russian Imperial Romanov family (Nicholas II of Russia, his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, and their five children: Olga, Tatiana, Maria, Anastasia, and Alexei) were shot and bayoneted to death[2][3] by Bolshevik revolutionaries under Yakov Yurovsky on the orders of the Ural Regional Soviet in Yekaterinburg on the night of 16–17 July 1918.

Also murdered that night were members of the imperial entourage who had accompanied them: court physician Eugene Botkin; lady-in-waiting Anna Demidova; footman Alexei Trupp; and head cook Ivan Kharitonov.

[22] Some Western historians attribute the execution order to the government in Moscow, specifically Vladimir Lenin and Yakov Sverdlov, who wanted to prevent the rescue of the imperial family by the approaching Czechoslovak Legion during the ongoing Russian Civil War.

[25] However, other historians have cited documented orders from the All-Russian Central Committee of the Soviets preferring a public trial for Nicholas II with Trotsky as chief prosecutor and his family spared.

[36] The imperial family was subjected to regular searches of their belongings, confiscation of their money for "safekeeping by the Ural Regional Soviet's treasurer",[37] and attempts to remove Alexandra's and her daughters' gold bracelets from their wrists.

[65] During the imperial family's imprisonment in late June, Pyotr Voykov and Alexander Beloborodov, president of the Ural Regional Soviet,[66] directed the smuggling of letters written in French to the Ipatiev House.

[67] On 13 July, across the road from the Ipatiev House, a demonstration of Red Army soldiers, Socialist Revolutionaries, and anarchists was staged on Voznesensky Square, demanding the dismissal of the Yekaterinburg Soviet and the transfer of control of the city to them.

[66] They agreed that the presidium of the Ural Regional Soviet under Beloborodov and Goloshchyokin should organize the practical details for the family's execution and decide the precise day on which it would take place when the military situation dictated it, contacting Moscow for final approval.

[72] The killing of the Tsar's wife and children was also discussed, but it was kept a state secret to avoid any political repercussions; German ambassador Wilhelm von Mirbach made repeated enquiries to the Bolsheviks concerning the family's well-being.

[1] Having previously seized some jewelry, he suspected more was hidden in their clothes;[37] the bodies were to be stripped naked in order to obtain the rest (this, along with the mutilations, was aimed at preventing investigators from identifying them).

[81] This claim was consistent with that of a former Kremlin guard, Aleksey Akimov, who in the late 1960s stated that Sverdlov instructed him to send a telegram confirming the CEC's approval of the 'trial' (code for execution) but required that both the written form and ticker tape be returned to him immediately after the message was sent.

Yurovsky watched in disbelief as Nikulin spent an entire magazine from his Browning gun on Alexei, who was still seated transfixed in his chair; he also had jewels sewn into his undergarment and forage cap.

[100] Anna Demidova, Alexandra's maid, survived the initial onslaught but was quickly stabbed to death against the back wall while trying to defend herself with a small pillow which she had carried that was filled with precious gems and jewels.

[109]Aleksandr Lisitsyn of the Cheka, an essential witness on behalf of Moscow, was designated to promptly dispatch to Sverdlov soon after the executions of Nicholas and Alexandra's politically valuable diaries and letters, which would be published in Russia as soon as possible.

[110] Beloborodov and Nikulin oversaw the ransacking of the Romanov quarters, seizing all the family's personal items, the most valuable piled up in Yurovsky's office whilst things considered inconsequential and of no value were stuffed into the stoves and burned.

He ordered additional trucks to be sent out to Koptyaki whilst assigning Pyotr Voykov to obtain barrels of petrol, kerosene and sulphuric acid, and plenty of dry firewood.

[123] During transportation to the deeper copper mines on the early morning of 19 July, the Fiat truck carrying the bodies got stuck again in mud near Porosenkov Log ("Piglet's Ravine").

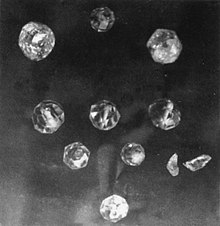

Among them were burned bone fragments, congealed fat,[130] Dr Botkin's upper dentures and glasses, corset stays, insignias and belt buckles, shoes, keys, pearls and diamonds,[9] a few spent bullets, and part of a severed female finger.

[139] Publication and worldwide acceptance of the investigation prompted the Soviets to issue a government-approved textbook in 1926 that largely plagiarized Sokolov's work, admitting that the empress and her children had been murdered with the Tsar.

[124] Leonid Brezhnev's Politburo deemed the Ipatiev House lacking "sufficient historical significance" and it was demolished in September 1977 by KGB chairman Yuri Andropov,[140] less than a year before the sixtieth anniversary of the murders.

[141] Local amateur sleuth Alexander Avdonin and filmmaker Geli Ryabov [ru] located the shallow grave on 30–31 May 1979 after years of covert investigation and a study of the primary evidence.

[142] The presidency of Mikhail Gorbachev brought with it the era of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (reform), which prompted Ryabov to reveal the Romanovs' gravesite to The Moscow News on 10 April 1989,[142] much to Avdonin's dismay.

[14][144] Although criminal investigators and geneticists identified them as Alexei and one of his sisters, either Maria or Anastasia,[145] they remain stored in the state archives pending a decision from the church,[146] which demanded a more "thorough and detailed" examination.

[153] However, in a final letter that was written to his children shortly before his death in 1938, he only reminisced about his revolutionary career and how "the storm of October" had "turned its brightest side" towards him, making him "the happiest of mortals";[154] there was no expression of regret or remorse over the murders.

[156] Lenin saw the House of Romanov as "monarchist filth, a 300-year disgrace",[157] and referred to Nicholas II in conversation and in his writings as "the most evil enemy of the Russian people, a bloody executioner, an Asiatic gendarme" and "a crowned robber.

Lenin was, however, aware of Vasily Yakovlev's decision to take Nicholas, Alexandra and Maria further on to Omsk instead of Yekaterinburg in April 1918, having become worried about the extremely threatening behavior of the Ural Soviets in Tobolsk and along the Trans-Siberian Railway.

Despite Yakovlev's request to take the family further away to the more remote Simsky Gorny District in Ufa province (where they could hide in the mountains), warning that "the baggage" would be destroyed if given to the Ural Soviets, Lenin and Sverdlov were adamant that they be brought to Yekaterinburg.

[160] Lenin also welcomed news of the death of Grand Duchess Elizabeth, who was murdered in Alapayevsk along with five other Romanovs on 18 July 1918, remarking that "virtue with the crown on it is a greater enemy to the world revolution than a hundred tyrant tsars".

[61][169] However, only the final resting places of Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna and her faithful companion Sister Varvara Yakovleva are known today, buried alongside each other in the Church of Mary Magdalene in Jerusalem.

[182] On Thursday, 26 August 2010, a Russian court ordered prosecutors to reopen an investigation into the murder of Tsar Nicholas II and his family, although the Bolsheviks believed to have shot them in 1918 had died long before.