Muskox

[8] Native to the Arctic, it is noted for its thick coat and for the strong odor emitted by males during the seasonal rut, from which its name derives.

[10] In historic times, muskoxen primarily lived in Greenland and the Canadian Arctic of the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

Instead, the muskox's closest living relatives appear to be the gorals of the genus Naemorhedus, nowadays common in many countries of central and east Asia.

[14] The modern muskox is the last member of a line of ovibovines that first evolved in temperate regions of Asia and adapted to a cold tundra environment late in its evolutionary history.

Later migration waves of Asian ungulates that included high-horned muskoxen reached Europe and North America during the first half of the Pleistocene.

The first well known muskox, the "shrub-ox" Euceratherium, crossed to North America over an early version of the Bering Land Bridge two million years ago and prospered in the American southwest and Mexico.

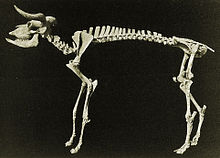

Euceratherium was larger yet more lightly built than modern muskoxen, resembling a giant sheep with massive horns, and preferred hilly grasslands.

Unlike Euceratherium, which survived in America until the Pleistocene-Holocene extinction event, Soergelia was a lowland dweller which disappeared fairly early, displaced by more advanced ungulates, such as the "giant muskox" Praeovibos (literally "before Ovibos").

Praeovibos was a highly adaptable animal apparently associated with cold tundra (reindeer) and temperate woodland (red deer) faunas alike.

It is debated, however, if Praeovibos was directly ancestral to Ovibos, or both genera descended from a common ancestor, since the two occurred together during the middle Pleistocene.

[14] Today's muskoxen are descended from others believed to have migrated from Siberia to North America between 200,000[16] and 90,000 years ago,[17] having previously occupied Alaska (at the time united to Siberia and isolated periodically from the rest of North America by the union of the Laurentide and Cordilleran Ice Sheets during colder periods) between 250,000 and 150,000 years ago.

The muskox was already present in its current stronghold of Banks Island 34,000 years ago, but the existence of other ice-free areas in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago at the time is disputed.

[14] Along with the bison and the pronghorn,[18] the muskox was one of a few species of Pleistocene megafauna in North America to survive the Pleistocene/Holocene extinction event and live to the present day.

[19] Muskox populations survived into the Holocene in Siberia, with their youngest records in the region being from the Taymyr Peninsula, dating to around 2,700 years ago (~700 BC).

[17] During the Wisconsinan, modern muskox thrived in the tundra south of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, in what is now the Midwest, the Appalachians and Virginia, while distant relatives Bootherium and Euceratherium lived in the forests of the Southern United States and the western shrubland, respectively.

[15] Though they were always less common than other Ice Age megafauna, muskox abundance peaked during the Würm II glaciation 20,000 years ago and declined afterwards, especially during the Pleistocene/Holocene extinction event, where its range was greatly reduced and only the populations in North America survived.

[30][failed verification] Following the disappearance of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, the muskox gradually moved north across the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, arriving in Greenland from Ellesmere Island at about 350 AD, during the late Holocene.

Human predation around Qaanaaq may have restricted muskoxen from moving down the west coast, and instead kept them confined to the northeastern fringes of the island.

The United States Fish and Wildlife Service introduced the muskox onto Nunivak Island in 1935 to support subsistence living.

In the 1950s, an American researcher and adventurer was able to capture muskox calves in Northern Canada for relocation to a property he prepared in Vermont.

When nets and ropes proved useless, he and his crew herded family groups into open water, where calves were successfully separated from the adults.

[citation needed] The Norwegian population on Dovrefjell is managed over an area of 340 km2 (130 sq mi) and in the summer of 2012 consisted of approximately 300 animals.

However, the pastures are marginal, with little grass available in winter (the muskox eats only plants, not lichen as reindeer do), and over time, inbreeding depression is expected in such a small population which originated from only a few introduced animals.

[46] One of the last of these actions was the release of six animals within the Pleistocene Park project area in the Kolyma River in 2010, where a team of Russian scientists led by Sergey Zimov aims to prove that muskoxen, along with other Pleistocene megafauna that survived into the early Holocene in northern Siberia,[47] did not disappear from the region due to climate change, but because of human hunting.

[48] Ancient muskox remains have never been found in eastern Canada, although the ecological conditions in the northern Labrador Peninsula are suitable for them.

[49] During the summer, muskoxen live in wet areas, such as river valleys, moving to higher elevations in the winter to avoid deep snow.

Muskoxen require a high threshold of fat reserves in order to conceive, which reflects their conservative breeding strategy.

[dubious – discuss][citation needed] Muskox are heterothermic mammals, meaning they have the ability to shut off thermal regulation in some parts of their body, like their lower limbs.

Muskoxen have a distinctive defensive behavior: when the herd is threatened, the adults will face outward to form a stationary ring or semicircle around the calves.

Analysis of extract of washes of the prepuce revealed the presence of benzoic acid and p-cresol, along with a series of straight-chain saturated hydrocarbons from C22H46 to C32H66 (with C24H50 being most abundant).