Detective fiction

[20] Literary critic Catherine Ross Nickerson credits Louisa May Alcott with creating the second-oldest work of modern detective fiction, after Poe's Dupin stories, with the 1865 thriller "V.V., or Plots and Counterplots."

Ross Nickerson notes that many of the American writers who experimented with Poe's established rules of the genre were women, inventing a subgenre of domestic detective fiction that flourished for several generations.

[29][31] Literary critics Chris Willis and Kate Watson consider Mary Elizabeth Braddon's first book, the even earlier The Trail of the Serpent (1861), to be the first British detective novel.

Detective fiction aimed at young male readers emerged as a distinct and highly popular subgenre in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras, particularly in British and American boys' weekly magazines.

Notable among these was Nelson Lee, created by John William Staniforth (writing as Maxwell Scott), who shared Blake's penchant for globe-trotting adventures and narrow escapes.

[38] The genre was characterized by several consistent features: most detectives had young assistants (like Blake's aide Tinker), operated from London addresses, and engaged in both domestic and international pursuits.

"[42] Another common convention in Golden Age detective stories involved an outsider–sometimes a salaried investigator or a police officer, but often a gifted amateur—investigating a murder committed in a closed environment by one of a limited number of suspects.

In 1896, a significant literary phenomenon unfolded in China with the rapid translation and serialization of four Sherlock Holmes stories in Shiwu bao (The Progress), a periodical established by the prominent reformist Liang Qichao.

These translations, undertaken by Zhang Kunde, marked an early introduction of Western detective fiction to Chinese readers, reflecting the broader intellectual currents of the time.

Among these were L’affaire Lerouge by Émile Gaboriau (1832–1873), published in 1903, John Thorndyke’s Cases by Richard Austin Freeman (1862–1943), which appeared in 1911, and Arsène Lupin, Gentleman Burglar by Maurice Leblanc (1864–1941), translated in 1914.

However, unlike earlier practices that emphasized Confucian virtues, Zhou’s commentaries critiqued the contemporary political system, often employing biting irony to mock the "antiquated" customs of imperial China.

Through their translations and commentaries, figures like Zhou Guisheng and Wu Jianren not only introduced Chinese readers to Western literary traditions but also used these works as a lens to examine and challenge the pressing issues of their own society[44].

This work laid the foundation for a series of stories centered on the character Huo Sang, a detective whose brilliance and methods bore a striking resemblance to those of Sherlock Holmes.

Indeed, the parallels between the two detectives are unmistakable: not only do their names share the same initials, but both characters are defined by their extraordinary intellect, their reliance on abductive reasoning, and their unwavering skepticism toward seemingly supernatural phenomena.

"Sadiq Mamquli, The Sherlock Holmes of Iran, The Sherriff of Isfahan" is the first major detective fiction in Persian, written by Kazim Musta'an al-Sultan (Houshi Daryan).

[51] Hemendra Kumar Roy was an Indian Bengali writer noted for his contribution to the early development of the genre with his 'Jayanta-Manik' and adventurist 'Bimal-Kumar' stories, dealing with the exploits of Jayanta, his assistant Manik, and police inspector Sunderbabu.

Other examples of early Russian detective stories include: "Bitter Fate" (1789) by M. D. Chulkov (1743–1792),[56] "The Finger Ring" (1831) by Yevgeny Baratynsky, "The White Ghost" (1834) by Mikhail Zagoskin, Crime and Punishment (1866) and The Brothers Karamazov (1880) by Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Popular pulp fiction magazines like Black Mask capitalized on this, as authors such as Carrol John Daly published violent stories that focused on the mayhem and injustice surrounding the criminals, not the circumstances behind the crime.

[61] His style of crime fiction came to be known as "hardboiled", a genre that "usually deals with criminal activity in a modern urban environment, a world of disconnected signs and anonymous strangers.

The "hardboiled" novel was a male-dominated field in which female authors seldom found publication until Marcia Muller, Sara Paretsky, and Sue Grafton were finally published in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

An inverted detective story, also known as a "howcatchem", is a murder mystery fiction structure in which the commission of the crime is shown or described at the beginning,[65] usually including the identity of the perpetrator.

Cozy mysteries feature minimal violence, sex, and social relevance; a solution achieved by intellect or intuition rather than police procedure, with order restored in the end; honorable characters; and a setting in a closed community.

Following other conventions of classic detective fiction, the reader is normally presented with the puzzle and all of the clues, and is encouraged to solve the mystery before the solution is revealed in a dramatic climax.

After the credits of Billy Wilder's film Witness for the Prosecution, the cinemagoers are asked not to talk to anyone about the plot so that future viewers will also be able to fully enjoy the unravelling of the mystery.

[73] Similarly, TV heroine Jessica Fletcher of Murder, She Wrote was confronted with bodies wherever she went, but most notably in her small hometown of Cabot Cove, Maine; The New York Times estimated that, by the end of the series' 12-year run, nearly 2% of the town's residents had been killed.

As global interconnectedness makes legitimate suspense more difficult to achieve, several writers—including Elizabeth Peters, P. C. Doherty, Steven Saylor, and Lindsey Davis—have eschewed fabricating convoluted plots in order to manufacture tension, instead opting to set their characters in some former period.

[82] The detective's adventures spanned multiple formats including comic strips, novels, radio serials, silent films, and a 1960s ITV television series, reaching audiences across Britain and internationally in various languages.

Initially conceived as a Victorian gentleman detective, Blake evolved significantly over time, acquiring now-iconic elements like his Baker Street residence, his young assistant Tinker, his bloodhound Pedro, and his housekeeper Mrs. Bardell.

Blake had many rivals and imitators: Nelson Lee, Dixon Hawke, Carfax Baines, Kenyon Ford, Stanley Dare, Ferrers Locke, and many others now long forgotten.

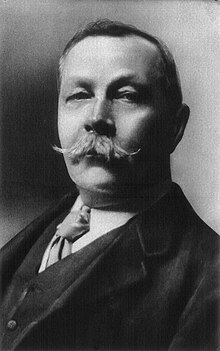

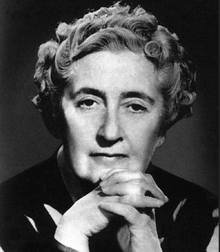

C. Auguste Dupin is generally acknowledged as the prototype for many fictional detectives that were created later, including Sherlock Holmes by Arthur Conan Doyle and Hercule Poirot by Agatha Christie.