N1 (rocket)

The N1 (from Ракета-носитель Raketa-nositel', "Carrier Rocket"; Cyrillic: Н1)[5] was a super heavy-lift launch vehicle intended to deliver payloads beyond low Earth orbit.

Adverse characteristics of the large cluster of thirty engines and its complex fuel and oxidizer feeder systems were not revealed earlier in development because static test firings had not been conducted.

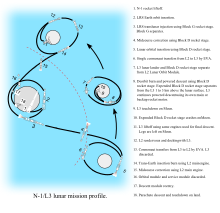

[9] The N1-L3 version was designed to compete with the United States Apollo program to land a person on the Moon, using a similar lunar orbit rendezvous method.

The N1/L3 program received formal approval in 1964, which required development of the N1 launch vehicle, comparable in size to the American Saturn V.[11] On 25 November 1967, less than three weeks after the first Saturn V flight during the Apollo 4 mission, the Soviets rolled out an N1 mockup to the newly constructed launch pad 110R at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Soviet Kazakhstan.

This Facilities Systems Logistic Test and Training Vehicle, designated 1M1, was designed to give engineers valuable experience in the rollout, launch pad integration, and rollback activities, similar to the Saturn V Facilities Integration Vehicle SA-500F testing at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida in mid-1966.

NASA Administrator James Webb had access to this and other similar intelligence that showed that the Russians were seriously planning crewed lunar missions.

During the same month, the report On Reconsideration of the Plans for Space Vehicles in the Direction of Defense Purposes set the first test launch of the N1 rocket for 1965.

At the same time, Korolev proposed a lunar mission based on the new Soyuz spacecraft using an Earth orbit rendezvous profile.

This approach, driven by the limited capacity of the Soyuz rocket, meant that a rapid launch rate would be required to assemble the complex before any of the components ran out of consumables on-orbit.

Korolev felt that the toxic nature of the fuels and their exhaust presented a safety risk for crewed space flight, and that kerosene/LOX was a better solution.

Kuznetsov, who had limited experience in rocket design, responded with the NK-15, a fairly small engine that would be delivered in several versions tuned to different altitudes.

[19] In January 1966, Korolev died due to complications of surgery to remove intestinal polyps that also discovered a large tumor.

[21] Mishin continued with the N1F project after the cancellation of plans for a crewed Moon landing in the hope that the booster would be used to build the Zvezda moonbase.

The boosters were deliberately broken up in an effort to cover up the USSR's failed Moon attempts, which was publicly stated to be a paper project in order to fool the US into thinking there was a race going on.

[35]: 199 [36][37] This exceeded the 33,700 kN (7,600,000 lbf) thrust of the Saturn V,[38] and the record would stand for over half a century, until the SpaceX Super Heavy surpassed it in 2023.

This was to negate the pitch or yaw moment diametrically opposing engines in the outer ring would generate, thus maintaining symmetrical thrust.

The second S-530 was located in the Soyuz LOK command module and provided control for the rest of the mission from TLI to lunar flyby and return to Earth.

[44] The complex plumbing needed to feed fuel and oxidizer into the clustered arrangement of rocket engines was fragile and a major factor in 2 of the 4 launch failures.

The fire then burned through wiring in the power supply, causing electrical arcing that was picked up by sensors and interpreted by the KORD as a pressurization problem in the turbopumps.

One unforeseen flaw was that its operating frequency, 1000 Hz, happened to perfectly coincide with vibration generated by the propulsion system, and the shutdown of Engine #12 at liftoff was believed to have been caused by pyrotechnic devices opening a valve, which produced a high-frequency oscillation that went into adjacent wiring and was assumed by the KORD to be an overspeed condition in the engine's turbopump.

[51][52] According to Sergei Afanasiev, the logic of the command to shut down the entire cluster of 30 engines in Block A was incorrect in that instance, as the subsequent investigation revealed.

[54] The nearly 2300 tons of propellant on board triggered a massive blast and shock wave that shattered windows across the launch complex and sent debris flying as far as 10 kilometers (6 miles) from the center of the explosion.

[55] The launch escape system had activated at the moment of engine shutdown (T+15 seconds) and pulled the L1S-2 capsule to safety 2.0 kilometers (1.2 miles) away.

Working theories were that either a piece of a pressure sensor had broken off and lodged in the pump, or that its impeller blades had rubbed against the metal casing, creating a friction spark that had ignited the LOX.

Kuznetsov succeeded in getting the postflight investigative committee to rule the cause of the engine failure as "ingestion of foreign debris".

[52] Vladimir Barmin, chief director of launch facilities at Baikonur, also argued that the KORD should be locked for the first 15–20 seconds of flight to prevent a shutdown command from being issued until the booster had cleared the pad area.

[56][57] The destroyed complex was photographed by American satellites, disclosing to the Western World that the Soviet Union had been constructing a Moon rocket.

The KORD computer sensed an abnormal situation and sent a shutdown command to the first stage, but as noted above, the guidance program had since been modified to prevent this from happening until 50 seconds into launch.

Despite the engine shutoff, the first and second stages still had enough momentum to travel for some distance before falling to earth about 15 kilometers (9 miles) from the launch complex and blasting a 15-meter-deep (50-foot) crater in the steppe.

At T+90 seconds, a programmed shutdown of the core propulsion system (the six center engines) was performed to reduce structural stress on the booster.