Nanban trade

The Nanban trade declined in the early Edo period with the rise of the Tokugawa Shogunate which feared the influence of Christianity in Japan, particularly the Roman Catholicism of the Portuguese.

The Tokugawa issued a series of Sakoku policies that increasingly isolated mainland Japan from the outside world and limited European trade to Dutch traders on the artificial island of Dejima, under total scrutiny.

[3]The first comprehensive and systematic report of a European about Japan is the Tratado em que se contêm muito sucinta e abreviadamente algumas contradições e diferenças de costumes entre a gente de Europa e esta província de Japão of Luís Fróis, in which he described Japanese life concerning the roles and duties of men and women, children, Japanese food, weapons, medicine, medical treatment, diseases, books, houses, gardens, horses, ships and cultural aspects of Japanese life like dances and music.

[4] Several decades later, when Hasekura Tsunenaga became the first Japanese official arriving in Europe, his presence, habits and cultural mannerisms gave rise to many picturesque descriptions circulating among the public: Renaissance Europeans were quite fond of Japan's immense richness in precious metals, mainly owing to Marco Polo's accounts of gilded temples and palaces, but also to the relative abundance of surface ores characteristic of a volcanic country, before large-scale deep-mining became possible in Industrial times.

[12] The state of civil-war in Japan was also highly beneficial to the Portuguese, as each competing lord sought to attract trade to their domains by offering better conditions.

Among the vessels involved in the trade linking Goa and Japan, the most famous were Portuguese carracks, slow but large enough to hold a great deal of merchandise and enough provisions to travel safely through such a lengthy and often hazardous (because of pirates) journey.

[15][16] Many of these were built at the royal Indo-Portuguese shipyards at Goa, Bassein or Daman, out of high-quality Indian teakwood rather than European pine, and their build quality became renowned; the Spanish in Manila favoured Portuguese-built vessels,[16] and commented that they were not only cheaper than their own, but "lasted ten times as long".

[18] In the 16th century, large junks belonging to private owners from Macau often accompanied the great ship to Japan, about two or three; these could reach about 400 or 500 tons burden.

[20] The English merchant Peter Mundy estimated that Portuguese investment at Canton ascended to 1,500,000 silver taels or 2,000,000 Spanish dollars.

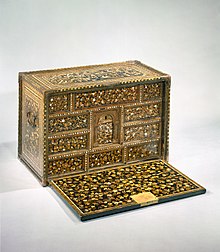

[25] Japanese lacquerware attracted European aristocrats and missionaries from Europe, and western style chests and church furniture were exported in response to their requests.

[29][30] In 1571, King Sebastian of Portugal issued a ban on the enslavement of both Chinese and Japanese, probably fearing the negative effects it might have on proselytization efforts as well as the standing diplomacy and trade between the countries.

[35][36] The overall profits from the Japan trade, carried on through the black ship, was estimated to ascend to over 600,000 cruzados, according to various contemporary authors such as Diogo do Couto, Jan Huygen van Linschoten and William Adams.

[39] The monopoly of Portugal on trade with Japan for a European nation started being challenged by Spanish ships from Manila after 1600 (until 1620[40]), the Dutch after 1609 and the English in 1613 (until 1623[41]).

Nonetheless, it was found that neither the Dutch nor the Spanish could effectively replace the Portuguese because Portugal had privileged access to Chinese markets and investors through Macau.

The head of the Pattani Dutch trading post, Victor Sprinckel, refused on the ground that he was too busy dealing with Portuguese opposition in Southeast Asia.

The Dutch also engaged in piracy and naval combat to weaken Portuguese and Spanish shipping in the Pacific, and ultimately became the only westerners to be allowed access to Japan from the small enclave of Dejima after 1639 and for the next two centuries.

The Japanese soon worked on various techniques to improve the effectiveness of their guns and even developed larger caliber barrels and ammunition to increase lethality.

The daimyo who initiated the unification of Japan, Oda Nobunaga, made extensive use of guns (arquebus) when playing a key role in the Battle of Nagashino, as dramatised in Akira Kurosawa's 1980 film Kagemusha (Shadow Warrior).

By the beginning of the 17th century, the shogunate had built, usually with the help of foreign experts, several ships of purely Nanban design, such as the galleon San Juan Bautista, which crossed the Pacific two times on embassies to Nueva España (Mexico).

Although the tolerance of Western "padres" was initially linked to trade, Catholics could claim around 200,000 converts by the end of the 16th century, mainly located in the southern island of Kyūshū.

It seems Hideyoshi's decision was taken following encouragements by the Jesuits to expel the rival order, his being informed by the Spanish that military conquest usually followed Catholic proselytism, and by his own desire to take over the cargo of the ship.

The final blow came with Tokugawa Ieyasu's firm interdiction of Christianity in 1614, which led to underground activities by the Jesuits and to their participation in Hideyori's revolt in the siege of Osaka (1614–1615).

Repression of Catholicism became virulent after Ieyasu's death in 1616, leading to the torturing and killing of around 2,000 Christians (70 westerners and the rest Japanese) and the apostasy of the remaining 200–300,000.

Some loanwords from Portuguese and Dutch have survived to this day: pan (パン, from pão, bread), tempura (天ぷら, from tempero, seasoning), botan (ボタン, from botão, button), karuta (カルタ, from cartas de jogar, playing cards), furasuko (フラスコ, from frasco, flask, bottle), marumero (マルメロ, from marmelo, quince), etc.

Some things from the New World came to Japan along with their names via the Portuguese and Spanish, such as: tabako (タバコ, from tabaco, tobacco derived from the Taíno of the Caribbean).

Nanban dishes are not American or European, but an odd variety not using soy sauce or miso but rather curry powder and vinegar as their flavoring, a characteristic derived from Indo-Portuguese Goan cuisine.