Nantes

Nantes (/nɒ̃t/, US also /nɑːnt(s)/;[3][4][5] French: [nɑ̃t] ⓘ; Gallo: Naunnt or Nantt [nɑ̃(ː)t];[6] Breton: Naoned [ˈnãunət])[7] is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, 50 km (31 mi) from the Atlantic coast.

[10] The European Commission noted the city's efforts to reduce air pollution and CO2 emissions, its high-quality and well-managed public transport system and its biodiversity, with 3,366 hectares (8,320 acres) of green space and several protected Natura 2000 areas.

[14] Its first recorded name was by the Greek writer Ptolemy, who referred to the settlement as Κονδηούινκον (Kondēoúinkon) and Κονδιούινκον (Kondioúinkon)[A]—which might be read as Κονδηούικον (Kondēoúikon)—in his treatise, Geography.

In Gallo, the oïl language traditionally spoken in the region around Nantes, the city is spelled Naunnt or Nantt and pronounced identically to French, although northern speakers use a long [ɑ̃].

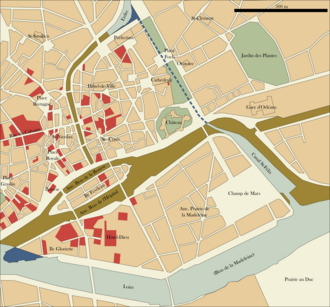

[23] Nantes's historical nickname was "Venice of the West" (French: la Venise de l'Ouest), a reference to the many quays and river channels in the old town before they were filled in during the 1920s and 1930s.

Despite initial successes with Spanish aid, in 1598 he submitted to Henry IV (who had by then converted to Catholicism); the Edict of Nantes (legalising Protestantism in France) was signed in the town, concluding the French wars of religion.

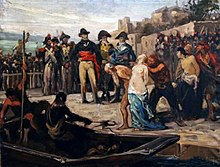

[54] Plantations in the colonies needed labour to produce sugar, rum, tobacco, indigo dye, coffee and cocoa, and Nantes shipowners began trading African slaves in 1706.

[57] Nantes and its surrounding area were the main producers of French printed cotton fabric during the 18th century,[58] and the Netherlands was the city's largest client for exotic goods.

These industries helped maintain port activity and facilitated agriculture, sugar imports, fertilizer production, machinery and metallurgy, which employed 12,000 people in Nantes and its surrounding area in 1914.

The main attacks occurred on 16 and 23 September 1943, when most of Nantes's industrial facilities and portions of the city centre and its surrounding area were destroyed by American bombs.

Land north of Nantes is dominated by bocage and dedicated to polyculture and animal husbandry, and the south is renowned for its Muscadet vineyards and market gardens.

[100] The Sillon de Bretagne is composed of granite; the rest of the region is a series of low plateaus covered with silt and clay, with mica schist and sediments found in lower areas.

After the union of Brittany and France, the burghers petitioned the French king to give them a city council which would enhance their freedom; their request was granted by Francis II in 1559.

Nantes Métropole administers urban planning, transport, public areas, waste disposal, energy, water, housing, higher education, economic development, employment and European topics.

[127] Local authorities began using official symbols in the 14th century, when the provost commissioned a seal on which the Duke of Brittany stood on a boat and protected Nantes with his sword.

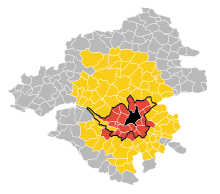

[135][136][137] Debate continues about Nantes's place in Brittany, with polls indicating a large majority in Loire-Atlantique and throughout the historic province favouring Breton reunification.

[180] The city's remaining port terminal still handles wood, sugar, fertiliser, metals, sand and cereals, ten percent of the total Nantes–Saint-Nazaire harbour traffic (along the Loire estuary).

[181] The Atlanpole technopole, in northern Nantes on its border with Carquefou, intends to develop technological and science sectors throughout the Pays de la Loire.

With a business incubator, it has 422 companies and 71 research and higher-education facilities and specialises in biopharmaceuticals, information technology, renewable energy, mechanics, food production and naval engineering.

The museum includes works by Tintoretto, Brueghel, Rubens, Georges de La Tour, Ingres, Monet, Picasso, Kandinsky and Anish Kapoor.

Items include paintings, sculptures, photographs, maps and furniture displayed to illustrate major points of Nantes history such as the Atlantic slave trade, industrialisation and the Second World War.

Collections include a golden reliquary made for Anne of Brittany's heart, medieval statues and timber frames, coins, weapons, jewellery, manuscripts and archaeological finds.

[217] Permanent sculptures include Daniel Buren's Anneaux (a series of 18 rings along the Loire reminiscent of Atlantic slave trade shackles) and works by François Morellet and Dan Graham.

[218] La Folle Journée (The Mad Day, an alternate title of Pierre Beaumarchais' play The Marriage of Figaro) is a classical music festival held each winter.

[219] The September Rendez-vous de l'Erdre couples a jazz festival with a pleasure-boating show on the Erdre,[220] exposing the public to a musical genre considered elitist; all concerts are free.

"Dans les prisons de Nantes" is the most popular, with versions recorded by Édith Piaf, Georges Brassens, Tri Yann and Nolwenn Leroy.

[229] During the 19th century Nantes-born gastronome Charles Monselet praised the "special character" of the local "plebeian" cuisine, which included buckwheat crepes, caillebotte fermented milk and fouace brioche.

[232] Local fishing ports such as La Turballe and Le Croisic mainly offer shrimp and sardines, and eels, lampreys, zander and northern pike are caught in the Loire.

[246] A new Aéroport du Grand Ouest in Notre-Dame-des-Landes, 20 kilometres (12 miles) north of Nantes, was projected from the 1970s, to create a hub serving north-western France.

Places publiques is dedicated to urbanism in Nantes and Saint-Nazaire; Brief focuses on public communication; Le Journal des Entreprises targets managers; Nouvel Ouest is for decision-makers in western France, and Idîle provides information on the local creative industry.