Napoleonic weaponry and warfare

"[1] Many factors contributed to Napoleon's ability to perform these flexible movements, from the division of his army into an independent corps system, to the avoidance of slow-moving, lengthy supply lines.

These factors, combined with Napoleon's innate persuasive ability to inspire his troops, resulted in successive victories in dominating fashion.

With the advent of cheap small arms and the rise of the drafted citizen soldier, army sizes increased rapidly to become mass forces.

During the Italian campaign, Napoleon conversed much about the warriors of antiquity, especially Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Scipio Africanus, and Hannibal.

"[3] Napoleon could win battles by concealing troop deployments and concentrating his forces on the "hinge" of an enemy's weakened front.

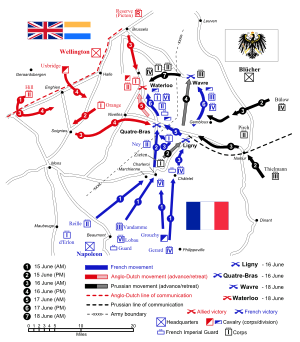

If he could not use his favourite envelopment strategy, he would take up the central position and attack two cooperating forces at their hinge, swing round to fight one until it fled, then turn to face the other.

The Battle of Austerlitz was a perfect example of this manoeuvre; Napoleon withdrew from a strong position to draw his opponent forward and tempt him into a flank attack, weakening his center.

Initially, the lack of force concentration helped with foraging for food and sought to confuse the enemy as to his real location and intentions.

It can be said that the Prussian Army under Field Marshal Gebhard Leberecht von Blücher used the "Manoeuvre De Derrière" against Napoleon who was suddenly placed in a position of reacting to a new enemy threat.

Napoleon's practical strategic triumphs, repeatedly leading smaller forces to defeat larger ones, inspired a whole new field of study into military strategy.

In particular, his opponents were keen to develop a body of knowledge in this area to allow them to counteract a masterful individual with a highly competent group of officers, or general staff.

The two most significant students of his work were Carl von Clausewitz, a Prussian with a background in philosophy, and Antoine-Henri Jomini, who had been one of Napoleon's staff officers.

One notable exception to Napoleon's "strategy of annihilation" and a precursor to trench warfare were the Lines of Torres Vedras during the Peninsular War.

As for the infantry soldier himself, Napoleon primarily equipped his army with the Charleville M1777 Revolutionnaire musket, a product from older designs and models.

A trained soldier could hit a man sized target at 100 yards but anything further required an increasing amount of luck,[5] the musket was wildly inaccurate at long range.

At 10 inches shorter, the carbine and the musketoon were less cumbersome, making them more suitable for the mobility that horseback riders required but at the expense of accuracy.

The British themselves were to lose General Robert Ross, himself a veteran of the Peninsular War, to American long range rifle fire in 1814.

With the development and improvement of combat weapons throughout the Seven Years' War prior to Napoleon, artillery had expanded to almost every European country, including France with 12-lb and 8-lb cannons.

Along with the artillery, the army had vast quantities of mortars, furnace bombs, grape and canister shots, all of which provided substantial support fire.

In 1798, Napoleon's flagship L’Orient, with 120 guns, was the most heavily armed vessel in the world;[6] until it was sunk that year at the Battle of the Nile.

A French tactic during the war was assembling a large amount of available guns into a 'Grand Battery' that would concentrate its fire on a single body of enemies or position to devastating effect.