Naqada culture

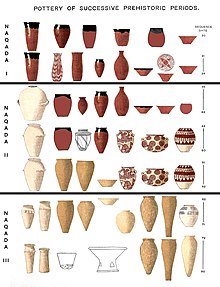

Many of the designs seen on pottery contain waves, sometimes accompanied by floral motifs or drawings of people, suggesting the importance of art in the Naqada Cultures.

Hunting the hippopotamus is noted to be important among the Naqada upper class as it was regarded as high social status although access to copper was more open to the elites rather than the common folk.

The wooden fences were replaced over time by mud brick walls as evident from the excavation at Tel-El Farkha.

[16] Also at the Tel-El Farkha sites is evidence of buildings: one of the biggest in the site was built on top of a mound and is surrounded by thick mud brick walls and inside the building are small poorly preserved rooms that were surrounded by 30–40 cm walls.

[15] Predynastic Egyptians in the Naqada I period traded with Nubia to the south, the oases of the western desert to the west, and the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean to the east.

[18][19] Charcoal samples found in the tombs of Nekhen, dated to the Naqada I and II periods, have been identified as cedar from Lebanon.

[20] In 1993 a craniofacial study was performed by the anthropologist C. Loring Brace, the report reached the view that "The Predynastic of Upper Egypt and the Late Dynastic of Lower Egypt are more closely related to each other than to any other population", and most similar to modern Egyptians among modern populations, stating "the Egyptians have been in place since back in the Pleistocene and have been largely unaffected by either invasions or migrations."

The craniometric analysis of predynastic Naqada human remains found that they were closely related to other Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting North Africa, parts of the Horn of Africa and the Maghreb, as well as to Bronze Age and medieval period Nubians and to specimens from ancient Jericho.

He concluded that 61-64% were classified as southern series (which shares closest affinities with Kerma Kushites), while 36-41% were more similar to the northern Egyptian pattern (Coastal Maghrebi).

In contrast, the set of Badarian crania were largely conforming to the Upper Egyptian-southern series at rates of 90-100%, with 9% possibly displaying northern affinities.

The Middle Eastern series had some similarities with the early Southern Upper Egyptians and Nubians, which was considered by the researcher probably a reflection of their real presence to some degree, a consideration attested by archeological and historical sources.

Keita and Boyce further added that the limb proportions of early Nile Valley remains were generally closer to tropical populations.

[27] In 1996, Lovell and Prowse reported the presence of individuals buried at Naqada in what they interpreted to be elite, high-status tombs, showing them to be an endogamous ruling or elite segment who were significantly different from individuals buried in two other, apparently nonelite cemeteries, and more closely related morphologically to populations in Northern Nubia (A-Group) than to neighbouring populations at Badari and Qena in southern Egypt.

[29] In 1999, Lovell summarised the findings of modern skeletal studies which had determined that "in general, the inhabitants of Upper Egypt and Nubia had the greatest biological affinity to people of the Sahara and more southerly areas" but exhibited local variation in an African context.

She also wrote that the archaeological and inscriptional evidence for contact between Egypt and Syro-Palestine "suggests that gene flow from these areas was very likely".

Further, the Nubian A-Group plotted nearer to the Egyptians and the Lachish sample placed more closely to Naqada than Badari.

[33] In 2023, Christopher Ehret reported that the physical anthropological findings from the "major burial sites of those founding locales of ancient Egypt in the fourth millennium BCE, notably El-Badari as well as Naqada, show no demographic indebtedness to the Levant".

He further commented that "members of this population did not migrate from somewhere else but were descendants of the long-term inhabitants of these portions of Africa going back many millennia".

Ehret also cited existing, archaeological, linguistic and genetic data which he argued supported the demographic history.

[34] Several scholars have highlighted a number of methodological limitations with the application of DNA studies to Egyptian mummified remains.