Nash equilibrium

[1] The idea of Nash equilibrium dates back to the time of Cournot, who in 1838 applied it to his model of competition in an oligopoly.

[3] Game theorists use Nash equilibrium to analyze the outcome of the strategic interaction of several decision makers.

Nash equilibrium requires that one's choices be consistent: no players wish to undo their decision given what the others are deciding.

The concept has been used to analyze hostile situations such as wars and arms races[4] (see prisoner's dilemma), and also how conflict may be mitigated by repeated interaction (see tit-for-tat).

It has been used to study the adoption of technical standards,[citation needed] and also the occurrence of bank runs and currency crises (see coordination game).

Other applications include traffic flow (see Wardrop's principle), how to organize auctions (see auction theory), the outcome of efforts exerted by multiple parties in the education process,[5] regulatory legislation such as environmental regulations (see tragedy of the commons),[6] natural resource management,[7] analysing strategies in marketing,[8] penalty kicks in football (I.e. soccer; see matching pennies),[9] robot navigation in crowds,[10] energy systems, transportation systems, evacuation problems[11] and wireless communications.

They showed that a mixed-strategy Nash equilibrium will exist for any zero-sum game with a finite set of actions.

The key to Nash's ability to prove existence far more generally than von Neumann lay in his definition of equilibrium.

Putting the problem in this framework allowed Nash to employ the Kakutani fixed-point theorem in his 1950 paper to prove existence of equilibria.

In 1965 Reinhard Selten proposed subgame perfect equilibrium as a refinement that eliminates equilibria which depend on non-credible threats.

Every correlated strategy supported by iterated strict dominance and on the Pareto frontier is a CPNE.

[20] Further, it is possible for a game to have a Nash equilibrium that is resilient against coalitions less than a specified size, k. CPNE is related to the theory of the core.

He considers an n-player game, in which the strategy of each player i is a vector si in the Euclidean space Rmi.

A common special case of the model is when S is a Cartesian product of convex sets S1,...,Sn, such that the strategy of player i must be in Si.

Rosen also proves that, under certain technical conditions which include strict concavity, the equilibrium is unique.

Nash equilibrium may also have non-rational consequences in sequential games because players may "threaten" each other with threats they would not actually carry out.

The combination (B,B) is a Nash equilibrium because if either player unilaterally changes their strategy from B to A, their payoff will fall from 2 to 1.

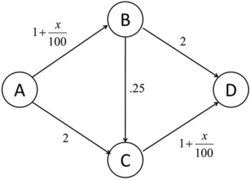

When that happens, no single driver has any incentive to switch routes, since it can only add to their travel time.

This is also the Nash equilibrium if the path between B and C is removed, which means that adding another possible route can decrease the efficiency of the system, a phenomenon known as Braess's paradox.

This can be illustrated by a two-player game in which both players simultaneously choose an integer from 0 to 3 and they both win the smaller of the two numbers in points.

This game has a unique pure-strategy Nash equilibrium: both players choosing 0 (highlighted in light red).

Stability is crucial in practical applications of Nash equilibria, since the mixed strategy of each player is not perfectly known, but has to be inferred from statistical distribution of their actions in the game.

Finally in the eighties, building with great depth on such ideas Mertens-stable equilibria were introduced as a solution concept.

[citation needed] If a game has a unique Nash equilibrium and is played among players under certain conditions, then the NE strategy set will be adopted.

The payoff in economics is utility (or sometimes money), and in evolutionary biology is gene transmission; both are the fundamental bottom line of survival.

The image to the right shows a simple sequential game that illustrates the issue with subgame imperfect Nash equilibria.

Therefore, if rational behavior can be expected by both parties the subgame perfect Nash equilibrium may be a more meaningful solution concept when such dynamic inconsistencies arise.

This section presents a simpler proof via the Kakutani fixed-point theorem, following Nash's 1950 paper (he credits David Gale with the observation that such a simplification is possible).

For this purpose, it suffices to show that This simply states that each player gains no benefit by unilaterally changing their strategy, which is exactly the necessary condition for a Nash equilibrium.

The prisoner's dilemma, for example, has one equilibrium, while the battle of the sexes has three—two pure and one mixed, and this remains true even if the payoffs change slightly.