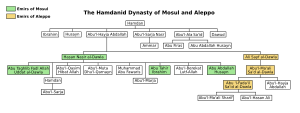

Nasir al-Dawla

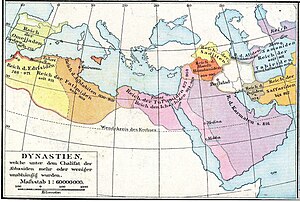

He was driven back to Mosul by Turkish troops, and subsequent attempts to challenge the Buyids who seized control of Baghdad and lower Iraq in 945 ended in repeated failure.

He raised troops among the Taghlib in exchange for tax remissions, and established a commanding influence in the Jazira by acting as a mediator between the Abbasid authorities and the Arab and Kurdish population.

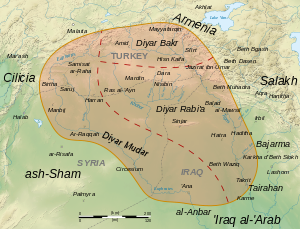

[11][13] In 930, after the caliph's governor died,[13] Hasan managed to regain control over Mosul, but his uncles Nasr and Sa'id soon removed him from power and confined him to the western parts of the Diyar Rabi'a.

[11][14] In the meantime, the defeated Banu Habib, some 10,000 strong and under the leadership of al-Ala ibn al-Mu'ammar, left their lands and fled to territory controlled by the Byzantine Empire.

[15] Ibn Ra'iq's position was anything but secure, however, and soon a convoluted struggle for control of his office, and the Caliphate with it, broke out among the various local rulers and the Turkish and Daylamite military chiefs, which ended in 946 with the ultimate victory of the Buyids.

[11] At first, Hasan tried to exploit the weakness of the Abbasid government to withhold his payment of tribute, but the Turk Bajkam, who had ousted Ibn Ra'iq in 938, quickly forced him to back down.

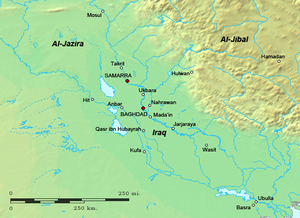

[11][17][18] Hasan's great chance came in early 942, when Caliph al-Muttaqi (r. 940–944) and his closest aides fled Baghdad to escape the city's imminent fall to the Baridis of Basra and sought refuge at Mosul.

Hasan now made a direct bid for power: he had Ibn Ra'iq assassinated and succeeded him as amir al-umara, receiving the honorific laqab of Nasir al-Dawla ('Defender of the Dynasty').

[11][18][19] Along with their cousin, Husayn ibn Sa'id, Nasir al-Dawla's brother Ali was instrumental in the Hamdanid enterprise, taking the field against the Baridis, who still controlled the rich province of Basra and were determined to regain Baghdad.

[11][14][20] This double award marked the first time that a laqab incorporating the prestigious element al-Dawla was granted to anyone other than the vizier, the Caliphate's chief minister, and was a symbolic affirmation of the military's predominance over the civil bureaucracy.

Consequently, when in late 943 a mutiny broke out among their troops (mostly composed of Turks, Daylamites, Carmathians and only a few Arabs) over pay issues, under the leadership of the Turkish general Tuzun, they were forced to quit Baghdad and return to their base, Mosul.

[21] Henceforth, Nasir al-Dawla would be tributary to Baghdad, but he would find it difficult to resign himself to his loss of power over the city he once ruled, and during subsequent years he would undertake several attempts to regain it.

His death weakened the Abbasid government's ability to maintain its independence against the rising power of the Buyids, who under Ahmad ibn Buya had already consolidated control over Fars and Kerman, and secured the cooperation of the Baridis.

In exchange, Nasir al-Dawla agreed to recommence the payment of tribute for the Jazira and Syria, as well as to add the names of the three Buyid brothers after that of the caliph in the Friday prayer.

While the Buyids were preoccupied with the rebellion of their Daylamite troops under Rezbahan ibn Vindadh-Khurshid in southern Iraq, Nasir al-Dawla took the opportunity to advance south and capture Baghdad.

[21][25] Peace was renewed in exchange for the recommencement of tribute and an additional indemnity, but when Nasir al-Dawla refused to send the second year's payment, the Buyid ruler advanced north.

The Buyids captured Mosul and Nasibin, but the Hamdanids and their supporters withdrew to their home territory in the mountains of the north, taking with them their treasures as well as all government records and tax registers.

[21][26] In 964, Nasir al-Dawla tried to renegotiate the terms of the arrangement, but also to secure Buyid recognition for his eldest son, Fadl Allah Abu Taghlib al-Ghadanfar, as his successor.

[21] In the end, Abu Taghlib, already the de facto governor of the emirate, deposed him with the aid of his Kurdish mother, Fatima bint Ahmad, who according to Ibn al-Athir exercised considerable influence over her husband's affairs.

[21] The traveller Ibn Hawqal, who visited Nasir al-Dawla's domains, reports in length on his seizure of private land in the most fertile regions of the Jazira, on flimsy legal pretexts, until he became the greatest landowner in his province.