Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Tusi is widely regarded as one of the greatest scientists of medieval Islam,[7] since he is often considered the creator of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline in its own right.

[12][13][14][15][16][17] Nasir al-Din Tusi was born in the city of Tus in medieval Khorasan (northeastern Iran) in the year 1201 and began his studies at an early age.

Fulfilling the wish of his father, the young Muhammad took learning and scholarship very seriously and traveled far and wide to attend the lectures of renowned scholars and acquired knowledge, an exercise highly encouraged in his Islamic faith.

[19] He met also Attar of Nishapur, the legendary Sufi master who was later killed by the Mongols, and he attended the lectures of Qutb al-Din al-Misri - a student of Al-Razi.

Nasir-al-Din Tusi writes in his work, Desideratum of the Faithful (Maṭlūb al-muʾminīn),“To become people of spiritual reality, it is incumbent to fulfill the symbolic elucidation (ta'wīl) of the seven pillars of the religious law (sharīʿat)”.

[20] He explains in his book Aghaz u anjam that the sacred accounts of history that we perceive within the bounds of space and time symbolize events that have no such restrictions.

[21] In Mosul, al-Tusi studied mathematics and astronomy with Kamal al-Din Yunus (d. AH 639 / AD 1242), a pupil of Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī.

[1] Later on he corresponded with Sadr al-Din al-Qunawi, the son-in-law of Ibn Arabi, and it seems that mysticism, as propagated by Sufi masters of his time, was not appealing to him.

Once the occasion was suitable, he composed his own manual of philosophical Sufism in the form of a small booklet entitled Awsaf al-Ashraf, or "The Attributes of the Illustrious".

After his forces destroyed Alamut, Hulegu, who was himself interested in the natural sciences, treated al-Tusi with great respect, appointing him as scientific adviser and a permanent member of his inner council.

[27] To great controversy, it is widely assumed Tusi was with the Mongol forces under Hulegu when they attacked and massacred the inhabitants of Baghdad in 1258[28] and he played an essential role in ending of the Quraysh Empire.

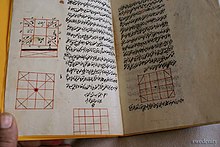

Writing in both Arabic and Persian, Nasir al-Din Tusi dealt with both religious ("Islamic") topics and non-religious or secular subjects ("the ancient sciences").

[34] Tusi convinced Hulegu Khan to construct an observatory for establishing accurate astronomical tables for better astrological predictions.

Beginning in 1259, the Rasad Khaneh observatory was constructed in Azarbaijan, south of the river Aras, and to the west of Maragheh, the capital of the Ilkhanate Empire.

His famous student Shams al-Din al-Bukhari[3] was the teacher of Byzantine scholar Gregory Chioniades,[38] who had in turn trained astronomer Manuel Bryennios[39] about 1300 in Constantinople.

He used this technique to replace Ptolemy's problematic equant[40] for many planets, but was unable to find a solution to Mercury, which was used later by Ibn al-Shatir as well as Ali Qushji.

[49] It was in the works of Al-Tusi that trigonometry achieved the status of an independent branch of pure mathematics distinct from astronomy, to which it had been linked for so long.

This text, which was copied in the Middle East numerous times until at least the nineteenth century as part of the textbook Revision of the Optics (Tanqih al-Manazir) by Kamal al-Din al-Farisi (d. 1320), made color space effectively two-dimensional.

Among plants, he considered the date-palm as the most highly developed, since "it only lacks one thing further to reach (the stage of) an animal: to tear itself loose from the soil and to move away in the quest for nourishment.

[59] The animals "which reach the stage of perfection [...] are distinguished by fully developed weapons", such as antlers, horns, teeth, and claws.

The greater this faculty grows in it, the more surpassing its rank, until a point is reached where the (mere) observation of action suffices as instruction: thus, when they see a thing, they perform the like of it by mimicry, without training [...].

In February 2013, Google celebrated his 812th birthday with a doodle, which was accessible in its websites with Arabic language calling him al-farsi (the Persian).

[12][13][14][15][16][17] al-Tusi specifically, the plagiarism in question comes from similarities in the Tusi couple and Copernicus' geometric method of removing the Equant from mathematical astronomy.

[13] There was just such a Jewish scholar by the name of Abner of Burgos who wrote a book containing an incomplete version of the Tusi couple that he had learned second hand, which could have been found by Copernicus.

[12] Additionally, some scholars believe that, if not Jewish thinkers, it could have been transmission from the Islamic school in Maragheh, home to Nasir al-Din al-Tusi's observatory to Muslim Spain.