Nation-building

According to Columbia University sociologist Andreas Wimmer, three factors tend to determine the success of nation-building over the long-run: "the early development of civil-society organisations, the rise of a state capable of providing public goods evenly across a territory, and the emergence of a shared medium of communication.

Nation-building can also include attempts to redefine the populace of territories that had been carved out by colonial powers or empires without regard to ethnic, religious, or other boundaries, as in Africa and the Balkans.

[13] In Latin America, 19th-century nation-building efforts led by elites not only established institutions like education, military defense, and civil rights but also often reinforced social hierarchies.

These new institutions were built with an awareness of the existing class divisions and power dynamics, shaping a national identity that excluded marginalized groups.

The more recent development of nation-states in geographically diverse, postcolonial areas may not be comparable due to differences in underlying conditions.

This sometimes resulted in their near-disintegration, such as the attempt by Biafra to secede from Nigeria in 1970, or the continuing demand of the Somali people in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia for complete independence.

The Rwandan genocide, as well as the recurrent problems experienced by the Sudan, can also be related to a lack of ethnic, religious, or racial cohesion within the nation.

The confusion over terminology has meant that more recently, nation-building has come to be used in a completely different context, with reference to what has been succinctly described by its proponents as "the use of armed force in the aftermath of a conflict to underpin an enduring transition to democracy".

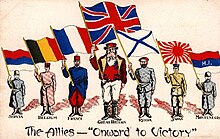

[23] In this sense, state-building is typically characterized by massive investment, military occupation, transitional government, and the use of propaganda to communicate governmental policy.

[5] European rulers during the 19th century relied on state-controlled primary schooling to teach their subjects a common language, a shared identity, and a sense of duty and loyalty to the regime.

[26][27] These beliefs about the power of education in forming loyalty to the sovereign were adopted by states in other parts of the world as well, in both non-democratic and democratic contexts.

In Japan, the victors were nominally in charge but in practice, the United States was in full control, again with considerable political, social, and economic impact.

The initial invasion of Afghanistan, intended to disrupt Al Qaeda's networks ballooned into a 20 year long nation building project.