National Guardian

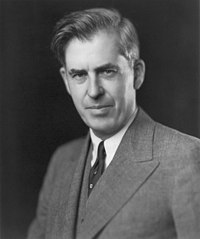

The paper was founded by James Aronson, Cedric Belfrage and John T. McManus in connection with the 1948 Presidential campaign of Henry A. Wallace under the Progressive Party banner.

As an official organ of the CPUSA, this publication was constrained by tight central direction and rather mechanical adherence to the party's political line — factors which somewhat limited the paper's appeal to radical American intellectuals.

[1] Among these journalists tapped to help "denazify" the country through establishment of a democratic press were James Aronson, a resident of New York City, and Englishman Cedric Belfrage, a former theatre critic for the London Daily Express who had since the 1930s lived in Hollywood, California where he worked as a screenwriter.

[2] Many American liberal and intellectuals were deeply disaffected with President Harry S. Truman and his hardline anti-Soviet foreign policy and perceived lack of commitment to New Deal social programs and sought an electoral alternative in the 1948 Presidential campaign.

[2] James Aronson and Cedric Belfrage were committed activists in the Wallace for President campaign and in the run-up to the Progressive Party nominating convention they renewed their acquaintance and revived plans for an independent radical newspaper in the United States.

[3] In July 1948 these four — with Gitt listed as publisher and Aronson, Belfrage, and McManus as editors — launched a sample publication called The National Gazette and circulated it at the Progressive Party Nominating Convention.

[6] The editors envisioned continued growth and a lowering of the paper's cover price, with a view to establishment of an influential mass weekly with a circulation of 500,000 or even 1,000,000 copies.

[7] With over 1 million voters casting ballots for Henry Wallace in November 1948, such a goal seemed within realization, and the editors tied their hopes to the continued growth and success of the Progressive Party movement.

[9] The paper was so closely tied to the Rosenberg defense that after the pair were executed on the electric chair for espionage, National Guardian editor James Aronson was named a trustee of the fund established on behalf of the couple's orphaned children.

[9] William A. Reuben, the National Guardian's main reporter on the Rosenberg case, later published an expanded version of his journalism in book form as The Atom Spy Hoax (1954).

[9] Throughout it all the National Guardian maintained friendly ties with the Communist Party USA, generally advancing a similar pro-Soviet and anti-militarist political line.

[9] The paper differed with the Communist Party primarily on the question of independent political action, which the CPUSA had abandoned as futile during the 1950s but which the National Guardian continued to support.

[9] Additional separation took place after Khrushchev's Secret Speech of 1956, including support of Yugoslav independence from the Soviet bloc and efforts at honest coverage of purges in Eastern Europe and the Hungarian Revolution.

The paper attempted to carve an independent role for itself, never formally aligning with any particular group and remaining critical of the plethora of small New Left party organizations which emerged after the demise of SDS in 1970.

The traditional news-first approach of the original National Guardian was gradually attenuated in the paper's outspokenly revolutionary 1970s incarnation, with editorial and commentary material supplanting straight news reporting.

[15] These party-building efforts ultimately failed, owing in some measure to the exhaustion of the Cultural Revolution in China as well as the lack of popular support for extreme political solutions and revolutionary phrasemaking in the United States.

By the decade of the 1980s the paper had begun to moderate its tone, lending critical support to revolutionary movements of whatever stripe, without regard to the Sino-Soviet split, and opening its pages to a range of diverse views by a broad spectrum of political activists.