National Peasants' Party

Supported by the Romanian Social Democrats, they expanded Romania's welfare state, but failed to tackle the Great Depression, and organized clampdowns against radicalized workers at Lupeni and Grivița.

[24] These events also overlapped with a dynastic crisis: after Ferdinand's death in July 1927, the throne went to his minor grandson Michael I—Michael's disgraced father Carol II having been forced to renounce his claim and pushed into exile.

[25] The unexpected death of PNL chairman Ion I. C. Brătianu pushed the PNȚ back into full-blown opposition: "All hopes [...] focused on the democratic movement of renewal, outstandingly represented by Iuliu Maniu.

[53] Despite its unprecedented success, the party was pushed into a defensive position by the Great Depression, and failed to enact many its various policy proposals; its support by workers and left-wing militants was affected during the strike actions of Lupeni and Grivița, which its ministers repressed with noted expediency.

[64][108] The Guards were supervised by a Military Section, comprising Army officials: Admiral Dan Zaharia was a member, alongside generals Ștefan Burileanu, Gheorghe Rujinschi, Gabriel Negrei, and Ioan Sichitiu.

[127] The scandal divided Romania's left-wing press: newspapers such as Adevărul remained committed to Maniu, though communist sympathizers such as Zaharia Stancu and Geo Bogza went back on their support for a PNȚ-led popular front, and switched to endorsing the PȚR.

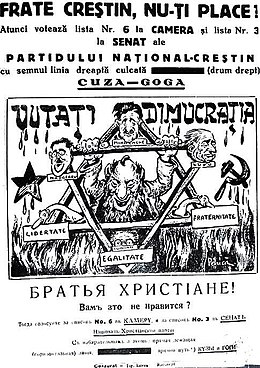

[141] At the height of the electoral campaign, the PNȚ and the PNL sought to obtain a new understanding with Carol, fearing that the PNC and the Iron Guard would form a powerful fascist alliance, and then a totalitarian state.

[144] The PNȚ again sought grassroots communist support: in Vâlcea County, it shared a list with the "Democratic Union", assigning eligible positions to a PCdR militant Mihail Roșianu and a communist-sympathizing priest, Ioan Marina.

The new government integrated much of the PNȚ's center, with Călinescu at Interior Affairs; Andrei, Ghelmegeanu, and Ralea, alongside Grigore Gafencu and Traian Ionașcu, became prominent FRN dignitaries,[149] as did Moldovan.

[165] This put an end to Carol's rule, bringing the country under an Iron Guard regime—the National Legionary State, with Antonescu as Conducător; though still neutral to 1941, Romania was now openly aligned with the Axis Powers.

[169] From late 1940, Maniu channeled anti-Nazi discontent by forming an association called Pro Transilvania and a newspaper, Ardealul, both of which reminded Romanians that Antonescu was not interested in a reversal of the Vienna Award.

[170] The Guardist takeover also pushed some National Peasantists into exile: facing a death sentence at home, Beza made his way to Cairo, where he formed a Free Romania Movement under British supervision.

German reports identified PNȚ-ist generals as most active in destroying the National Legionary regime;[174] armed PNȚ civilians, including Lupu, assisted the Army at various locations in Bucharest.

[178] Later that year, Maniu and Coposu engaged in encrypted correspondence with the Western Allies, preparing for an anti-Nazi takeover in Romania; they aligned themselves closely with Britain, seeking to obtain direct advice from Winston Churchill.

[185] Communist sources noted a discrepancy in repression statistics: while the elites were allowed to carry out a "paper war" with the regime, regular PNȚ militants risked imprisonment for expressing anti-fascist beliefs.

[217] The promotion of such comparatively minor figures was criticized by the party's youth, leaving Maniu to acknowledge the brain drain which had affected National Peasantism ever since Călinescu and Ralea's defections.

[223] Various reports, including oral testimonies by Peasant Guard members and volunteers who answered calls printed in Ardealul, suggest that local Hungarians were victims of numerous lynchings, either tolerated of encouraged by the Commissariat.

[233] Maniu was additionally assisted by a Permanent Delegation, whose members included Halippa, Hudiță, Lazăr, Teofil Sauciuc-Săveanu, Gheorghe Zane, as well as, with the introduction of women's suffrage, Ella Negruzzi.

[292] According to police reports, the PNȚ worked with YMCA and the Friends of America Association to build a solid base in Severin County, but was divided over the possibility of recruiting among the Iron Guard's clandestine networks.

[314] From August 1952, all those who had served as city or county leaders in four traditional parties, including the PNȚ and PNL, were automatically deported to penal colonies; some, like Șerban Cioculescu, were tacitly excepted, while an explicit pardon was granted to all of Alexandrescu's followers.

[322] During the following year, the regime resumed its persecution, targeting more minor National Peasantists, including a 7-man cell in Ploiești,[323] and arresting Vasile Georgescu Bârlad [ro] on charges that he was plotting to reestablish the party.

[328] Under Nicolae Ceaușescu, the PMR, renaming itself Romanian Communist Party (PCR), began extending recognition for interwar underground activists, or "illegalists", who were allowed to join its nomenklatura.

[385] As formulated by Țepelea, the struggle facing his party in 1945 was "to be, or not to be": "no longer an academic choice between monarchy and republic, but one opposing the defense of national identity with respect for some democratic principles to the acceptance of communist-imposed servitude.

"[372] In addition to sealing pacts with the minority parties, the PNȚ ran openly non-Romanian candidates on its lists; examples include Jews Tivadar Fischer,[391] Mayer Ebner[392] and Salomon Kinsbrunner, as well as Constantin Krakalia and Volodymyr Zalozetsky-Sas, who were Ukrainian.

[397] Connections between PNȚ-ists and minorities were reactivated after World War II, when the PNȚ registered mass enlistments by non-Romanian anti-communists, including Swabians in Lugoj[398] and Jews in Târgu Neamț.

[402] The party's Transylvanian circles criticized fascism from a moderate nationalist position: Iuliu Moldovan's "biopolitics" and scientific racism had numerous points of contact with far-right antisemitism, but always remained more democratic than similar programs advanced by Romanian fascists.

[403] Ionel Pop argued in 1936 that vandalizing Jewish property was a cowardly act and a deflection, hinting that "Christian parties" would have done better to focus on chasing out an "evil spirit" that lurked in the corridors of power.

[409] Anti-communism as expressed by the PNȚ's mainstream was also motivated by nationalist priorities, with party men such as Grigore Gafencu urging for the strong defense of Bessarabia against Soviet demands and incursions.

[427] As a corollary of his support for cooperative endeavors and defense of minority rights, Maniu championed Balkan federalism and Europeanism, both of which were referred to in his speeches of the 1920s and '30s; he viewed himself as agreeing with specific transnational proposals advanced by Nicolae Titulescu and André Tardieu.

[428] In part, such tenets reflected the PNȚ-ist stances on Transylvanian autonomy: Maniu regarded István Bethlen's autonomism as a front for Hungarian revisionism, and proposed instead that Hungary and Romania be joined into a Central European Confederation.