Nationality

The most common distinguishing feature of citizenship is that citizens have the right to participate in the political life of the state, such as by voting or standing for election.

[10] For when a person lacks nationality, globally only 23 countries have established dedicated statelessness determination procedures.

Individuals may also be considered nationals of groups with autonomous status that have ceded some power to a larger sovereign state.

[12] Within the broad limits imposed by a few treaties and international law, states may freely define who are and are not their nationals.

[36] As such nationality in international law can be called and understood as citizenship,[36] or more generally as subject or belonging to a sovereign state, and not as ethnicity.

Until the 19th and 20th centuries, it was typical for only a certain percentage of people who belonged to the state to be considered as full citizens.

In the past, a number of people were excluded from citizenship on the basis of sex, socioeconomic class, ethnicity, religion, and other factors.

Similarly, in the Republic of China, commonly known as Taiwan, the status of national without household registration applies to people who have the Republic of China nationality, but do not have an automatic entitlement to enter or reside in the Taiwan Area, and do not qualify for civic rights and duties there.

[38] In some countries, the cognate word for nationality in local language may be understood as a synonym of ethnicity or as an identifier of cultural and family-based self-determination, rather than on relations with a state or current government.

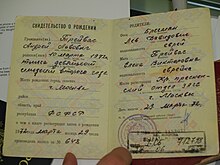

Membership in these groups was identified on Soviet internal passports, and recorded in censuses in both the USSR and Yugoslavia.

In the early years of the Soviet Union's existence, ethnicity was usually determined by the person's native language, and sometimes through religion or cultural factors, such as clothing.

In 2013, the Supreme Court of Israel unanimously affirmed the position that "citizenship" (e.g. Israeli) is separate from le'om (Hebrew: לאום; "nationality" or "ethnic affiliation"; e.g. Jewish, Arab, Druze, Circassian), and that the existence of a unique "Israeli" le'om has not been proven.

[40][41][42] The older ethnicity meaning of "nationality" is not defined by political borders or passport ownership and includes nations that lack an independent state (such as the Assyrians, Scots, Welsh, English, Andalusians,[43] Basques, Catalans, Kurds, Punjabis, Kabyles, Baluchs, Pashtuns, Berbers, Bosniaks, Palestinians, Hmong, Inuit, Copts, Māori, Wakhis, Xhosas and Zulus, among others).

Dual nationality is when a single person has a formal relationship with two separate, sovereign states.

Nationality, with its historical origins in allegiance to a sovereign monarch, was seen originally as a permanent, inherent, unchangeable condition, and later, when a change of allegiance was permitted, as a strictly exclusive relationship, so that becoming a national of one state required rejecting the previous state.

[44] Dual nationality was considered a problem that caused a conflict between states and sometimes imposed mutually exclusive requirements on affected people, such as simultaneously serving in two countries' military forces.

Through the middle of the 20th century, many international agreements were focused on reducing the possibility of dual nationality.

Another stateless situation arises when a person holds a travel document (passport) which recognizes the bearer as having the nationality of a "state" which is not internationally recognized, has no entry into the International Organization for Standardization's country list, is not a member of the United Nations, etc.

In the current era, persons native to Taiwan who hold passports of Republic of China are one example.