Nationalities and regions of Spain

Spain is a diverse country integrated by contrasting entities with varying economic and social structures, languages, and historical, political and cultural traditions.

[1][2] The Spanish constitution responds ambiguously to the claims of historic nationalities (such as the right of self-government) while proclaiming a common and indivisible homeland of all Spaniards.

The rest of the autonomous communities (Castile-La Mancha, Murcia, La Rioja, Extremadura) are defined as historical regions of Spain.

Scholars began to explore the histories of these regions, to tell their own founding stories: Catalonia rediscovered her prowess as a Mediterranean Medieval empire within the Crown of Aragon, and the Basque Country focused on the mystery of its origins.

[14][15] In the early twentieth century, nationalist discourse in Galicia, Catalonia and especially in the Basque country was infused with racialist elements, as these ethnicities defined themselves as distinct from the peoples of the center and south of Spain.

The appearance of the so-called peripheral nationalism in the aforementioned regions of Spain occurred in a period when Spaniards began to look into their own concepts of nationhood.

In the traditionalist view, religion had been integral to defining the Spanish nation, intrinsically and traditionally Catholic, and strongly monarchical.

[8][17] On 11 September 1977, more than one million people marched in the streets of Barcelona (Catalonia) demanding "llibertat, amnistia i estatut d'autonomia", "liberty, amnesty and [a] Statute of Autonomy", creating the biggest demonstration in post-war Europe.

The demands for the recognition of the distinctiveness of Catalonia, the Basque Country and Galicia, within the Spanish State became one of the most important challenges for the newly elected Parliament.

[20] The Preamble to the constitution explicitly stated that it is the Nation's will to protect "all Spaniards and the peoples of Spain in the exercise of their human rights, cultures traditions, languages and institutions".

The third article ends up declaring that the "richness of the distinct linguistic modalities of Spain represent a patrimony which will be the object of special respect and protection.

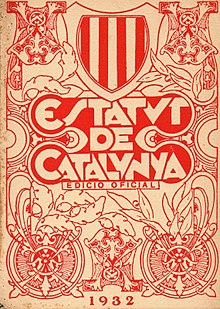

The three "historic nationalities" (Catalonia, Galicia and the Basque Country) were granted a simplified "fast-track" process, while the rest of the regions had to follow a specific set of requirements.

First, it did not specify the name or number of the autonomous communities that would integrate the Spanish nation, and secondly, the process was voluntary in nature: the regions themselves had the option of choosing to attain self-government or not.

Though highly decentralised, this system is not a federation, in that there was still ambiguity with regards to the power attributed to the regions, even though they can still negotiate them with the central government.

The other regions had the opportunity to accede to autonomy via the slower route established in the 143rd article, with a lower level of competencies, during a provisional period of five years.

Despite having a Basque-speaking minority, the province of Navarre chose not to join the soon-to-be formed autonomous community of the Basque Country.

Both the Basque Country and Navarre are considered "communities of chartered regime", meaning they have fiscal autonomy: they collect their own taxes and send a prearranged amount to the central government.

[8][26] Despite the lack of historical basis for both communities, and the fact that the Spanish government favored their integration in the larger Castile-León, the local population overwhelmingly supported the new entities.

[27] In Cantabria, one of the leading intellectual figures in 19th-century Spain, Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo, had already rejected a Castilian identity for his region as far back as 1877, instead favouring integration with its western neighbour, Asturias: ¡Y quién sabe si antes de mucho, enlazadas hasta oficialmente ambas provincias, rota la ilógica división que a los montañeses nos liga a Castilla, sin que seamos, ni nadie nos llame castellanos, podrá la extensa y riquísima zona cántabro-asturiana formar una entidad tan una y enérgica como la de Cataluña, luz y espejo hoy de todas las gentes ibéricas!

Can the extensive and rich Cantabro-Asturian region form an entity as unified and energetic as Catalonia, today the light and mirror of all the Iberian peoples!The province of Madrid was also separated from New Castile and constituted as an autonomous community.

This was partly in recognition of Madrid's status as the capital of the nation,[8] but also because it was originally excluded from the pre-autonomic agreements that created the community of Castile-La Mancha, to which it naturally belonged.

[29] Some peripheral nationalists still complain that the creation of many regions was an attempt to break down their own 'national unity' by a sort of gerrymandering,[8] thus blurring the distinctiveness of their own nationalities.

In the Basque Country in 2003, the regional government proposed a plan whereby the autonomous community would become a "free associated State" of Spain, which was later rejected by the Spanish Parliament.

In practical terms, the majority of the population has been satisfied with the framework of devolution since the restoration of democracy,[1][8] even if some still aspire for further recognition of the distinctiveness of the nationalities or for the expansion of their self-government.

[8] In all three "historical nationalities", there is still a sizable minority,[31][32][33] more so in Catalonia than in the Basque Country and Galicia, calling for the establishment of a true federal State in Spain or advocating for their right to self-determination and independence.

Before its dissolution, the Catalan parliament approved a bill calling for the next legislature to allow Catalonia to exercise its right of self-determination by holding a "referendum or consultation" during the next four years in which the people would decide whether to become a new independent and sovereign State.

[45][46] In December 2012, an opposing rally was organised by the Partido Popular and Ciutadans, which drew 30,000-160,000 people in one of Barcelona's main squares under a large flag of Spain and Catalonia.