Natural History Museum, London

The museum is home to life and earth science specimens comprising some 80 million items within five main collections: botany, entomology, mineralogy, palaeontology and zoology.

Dr George Shaw (Keeper of Natural History 1806–1813) sold many specimens to the Royal College of Surgeons and had periodic cremations of material in the grounds of the museum.

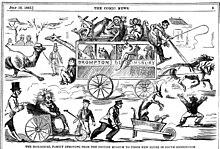

[10][11][12] J. E. Gray (Keeper of Zoology 1840–1874) complained of the incidence of mental illness amongst staff: George Shaw threatened to put his foot on any shell not in the 12th edition of Linnaeus' Systema Naturae; another had removed all the labels and registration numbers from entomological cases arranged by a rival.

The huge collection of the conchologist Hugh Cuming was acquired by the museum, and Gray's own wife had carried the open trays across the courtyard in a gale: all the labels blew away.

In 1835 to a Select Committee of Parliament, Sir Henry Ellis said this policy was fully approved by the Principal Librarian and his senior colleagues.

[11] Many of these faults were corrected by the palaeontologist Richard Owen, appointed Superintendent of the natural history departments of the British Museum in 1856.

[13] Owen saw that the natural history departments needed more space, and that implied a separate building as the British Museum site was limited.

[15] To give the project to the second-place winner would have been viewed as disrespectful to Fowke's memory, and instead the decision was made to expand on his original plans.

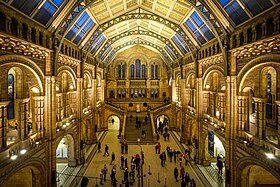

[14] The scheme was taken over by Alfred Waterhouse, who was hired in February 1866,[16] and who substantially revised the agreed plans, and designed the façades in his own idiosyncratic Romanesque style, which was inspired by his frequent visits to the Continent.

Waterhouse spent time with those in charge of each department of the museum to learn more about their needs, which helped him clarify his plans before construction began.

[15] Both the interiors and exteriors of the Waterhouse building make extensive use of architectural terracotta tiles to resist the sooty atmosphere of Victorian London, manufactured by the Tamworth-based company of Gibbs and Canning.

This explicit separation was at the request of Owen, and has been seen as a statement of his contemporary rebuttal of Darwin's attempt to link present species with past through the theory of natural selection.

The sculptures were produced from clay models by a French sculptor based in London, M Dujardin, working to drawings prepared by the architect.

The central atrium design by Neal Potter overcame visitors' reluctance to visit the upper galleries by "pulling" them through a model of the Earth made up of random plates on an escalator.

It was designed by the Danish architecture practice C. F. Møller Architects in the shape of a giant, eight-story cocoon and houses the entomology and botanical collections—the 'dry collections'.

[23] It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily.

The studio holds regular lectures and demonstrations, including free Nature Live talks on Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

The cast was given as a gift by the Scottish-American industrialist Andrew Carnegie, after a discussion with King Edward VII, then a keen trustee of the British Museum.

[28] At this time, it was first displayed in the Mammals (blue whale model) gallery, but now takes pride of place in the museum's Hintze Hall.

Before the door was closed and sealed forever, some coins and a telephone directory were placed inside—this soon growing to an urban myth that a time capsule was left inside.

[30] The Darwin Centre is host to Archie, an 8.62-metre-long giant squid taken alive in a fishing net near the Falkland Islands in 2004.

It is possible for members of the public to visit and view non-exhibited items behind the scenes for a fee by booking onto one of the several Spirit Collection Tours offered daily.

Since few complete and reasonably fresh examples of the species exist, "wet storage" was chosen, leaving the squid undissected.

Dinocochlea, one of the longer-standing mysteries of paleontology (originally thought to be a giant gastropod shell, then a coprolite, and now a concretion of a worm's tunnel), has been part of the collection since its discovery in 1921.

The museum keeps a wildlife garden on its west lawn, on which a potentially new species of insect resembling Arocatus roeselii was discovered in 2007.

These include for example a highly praised "How Science Works" hands on workshop for school students demonstrating the use of microfossils in geological research.

The museum also played a major role in securing designation of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and has subsequently been a lead partner in the Lyme Regis Fossil Festivals.

In 2005, the museum launched a project to develop notable gallery characters to patrol display cases, including 'facsimiles' of Carl Linnaeus, Mary Anning, Dorothea Bate and William Smith.

She kidnaps Paddington, intending to kill and stuff him, but is thwarted by the Brown family after scenes involving chases inside and on the roof of the building.

( link to current floor plans )