Natural history

[3] Medieval European academics considered knowledge to have two main divisions: the humanities (primarily what is now known as classics) and divinity, with science studied largely through texts rather than observation or experiment.

I like to think, then, of natural history as the study of life at the level of the individual—of what plants and animals do, how they react to each other and their environment, how they are organized into larger groupings like populations and communities"[7] and this more recent definition by D.S.

It often and appropriately includes an esthetic component",[12] and T. Fleischner, who defines the field even more broadly, as "A practice of intentional, focused attentiveness and receptivity to the more-than-human world, guided by honesty and accuracy".

Prior to the advent of Western science humans were engaged and highly competent in indigenous ways of understanding the more-than-human world that are now referred to as traditional ecological knowledge.

Natural history was understood by Pliny the Elder to cover anything that could be found in the world, including living things, geology, astronomy, technology, art, and humanity.

[20] Natural history was basically static through the Middle Ages in Europe—although in the Arabic and Oriental world, it proceeded at a much brisker pace.

From the 13th century, the work of Aristotle was adapted rather rigidly into Christian philosophy, particularly by Thomas Aquinas, forming the basis for natural theology.

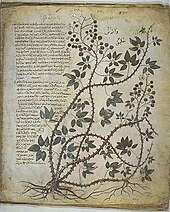

During the Renaissance, scholars (herbalists and humanists, particularly) returned to direct observation of plants and animals for natural history, and many began to accumulate large collections of exotic specimens and unusual monsters.

Other important contributors to the field were Valerius Cordus, Konrad Gesner (Historiae animalium), Frederik Ruysch, and Gaspard Bauhin.

[23] Since early modern times, however, a great number of women made contributions to natural history, particularly in the field of botany, be it as authors, collectors, or illustrators.

[25] Particularly in Britain and the United States, this grew into specialist hobbies such as the study of birds, butterflies, seashells (malacology/conchology), beetles, and wildflowers; meanwhile, scientists tried to define a unified discipline of biology (though with only partial success, at least until the modern evolutionary synthesis).

Three of the greatest English naturalists of the 19th century, Henry Walter Bates, Charles Darwin, and Alfred Russel Wallace—who knew each other—each made natural history travels that took years, collected thousands of specimens, many of them new to science, and by their writings both advanced knowledge of "remote" parts of the world—the Amazon basin, the Galápagos Islands, and the Indonesian Archipelago, among others—and in so doing helped to transform biology from a descriptive to a theory-based science.

Humboldt's copious writings and research were seminal influences for Charles Darwin, Simón Bolívar, Henry David Thoreau, Ernst Haeckel, and John Muir.

[26] Natural history museums, which evolved from cabinets of curiosities, played an important role in the emergence of professional biological disciplines and research programs.

Particularly in the 19th century, scientists began to use their natural history collections as teaching tools for advanced students and the basis for their own morphological research.